The Long Blue Line blog series has been publishing Coast Guard history essays for over 15 years. To access hundreds of these service stories, visit the Coast Guard Historian’s Office’s Long Blue Line online archives, located here: THE LONG BLUE LINE (uscg.mil)

PART I

Born, raised, and retired within 30 miles of each other, BMCM Maurice C. Poulin, U.S. Coast Guard retired, and PFC Charles B. Cossaboom, U.S. Army National Guard, served together two months in World War II. The latter, my father-in-law, grew up in Waltham, Massachusetts, before his Army service which included one year of training, one year of combat and one year in Army hospitals after being wounded in the Italian campaign. Returning from the war, he raised a family of three daughters and one son in Newton, Massachusetts, and worked as a watchmaker, jeweler, and assembler of aerospace gyroscopes for Draper Labs. In the movie Apollo 13, when a malfunction destroys many of the spacecraft’s operating systems, Jim Lovell asks the crew what equipment is still working and is told that the gyro is still “up.” The family likes to believe that it’s their father’s dependable handiwork that helped the crew return to Earth.

|

Master Chief Poulin followed a different path after growing up in Lowell, Massachusetts. Enlisting in the Coast Guard only weeks before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, he underwent basic training in New Orleans, Louisiana, and was sent to Cape Lookout, North Carolina, for his first duty station. Learning beach cart drills, Morse code, and how to resuscitate survivors of the tankers torpedoed offshore by German submarines, Poulin became a surfboat crewmember. Forgetting the bitter lessons learned in the First World War, U.S. coastal shipping at the start of World War II was not organized into convoys with Navy and Coast Guard escorts. In 1942, this resulted in heavy losses of individual tankers and freighters to German “Wolf Packs” a few miles off the U.S. shoreline. Because U-boats attacked at night and on the surface at this time, Coast Guard rescue boats hauling wounded mariners aboard occasionally encountered enemy submarines in the area. Poulin learned that on a few occasions U-boat captains would hail the surfboats in English, allowing them to continue their lifesaving work without interference if they promised not to call the Coast Guard shore station with the position of the submarine.

Further training for Poulin followed at the Coast Guard’s Boatswains Mate School at Manhattan Beach in Brooklyn, New York. There he learned marlinspike seamanship and how to handle small boats and small arms. Completing his training, Poulin was assigned to Chicamicomico Lifeboat Station, but in two days (probably before he could even learn how to pronounce the station’s name!), the Coast Guard transferred him to USS Leonard Wood (APA 12), homeported in Norfolk, Virginia. He would serve on board this attack transport ship from April 1942 until June 1945, seeing combat in both the Atlantic and Pacific war zones.

|

What was a Coast Guard boatswain doing on a Navy ship? During World War II, the Coast Guard provided complete crews for nine Navy attack transports, 76 Landing Ship, Tanks (LSTs), 30 Destroyer Escorts (DEs), several supply ships, countless landing craft (LCVPs), other smaller troop transports and service craft, as well as partial crew complements on other Navy ships. Poulin had plenty of Coast Guard company on board Leonard Wood. In the crew, there were 667 men with Coast Guard Captain Merlin O’Neill commanding during most of Poulin’s time on board. Designed to carry 1,962 soldiers or marines and their gear, USS Leonard Wood was 535 feet long and displaced nearly 22,000 tons.

On the Leonard Wood, Poulin was immediately impressed with the size of the ship and his responsibility for safely operating a winch and crane that would launch one of the 34 LCVPs, two tank lighters or two assault support boats. After practicing the art of amphibious invasion in Chesapeake Bay the transport loaded the Army’s 3rd Division onboard and sailed for an undisclosed port. Once at sea and out of earshot of any spies, the crew was told that they would be participating in the Allies’ first major amphibious landing in World War II at Fedala (located north of Casablanca) in French Morocco, North Africa. Poulin enjoyed the trans-Atlantic crossing--his first experience sailing on a large ship--and took as a good omen dolphins leaping and cavorting ahead of Leonard Wood’s bow wake.

|

With a good working knowledge of French, Poulin was assigned to the invasion’s beach party team as a translator. Because German officers had been assigned to stiffen Vichy French resistance to an invasion, the Allies were unsure what sort of reception awaited them. U.S. forces were told that a steady light would shine up from the shore if the landing would be unopposed, and that light was projected upwards. However, as the landing barges approached the beach, French artillery blasted several of the landing craft. Poulin rode ashore on top of a tank and hit the beach with General George Patton. Patton lived up to his reputation by refusing to dive into a trench when a German Messerschmitt strafed U.S. troops, and berating those, including his aide, who did take cover.

After spending the next day offloading fuel and supplies from the transport ships, Poulin rode into town and convinced local civilians to volunteer their trucks to the Army to ship essential material to the front lines. Meanwhile, a U-boat wolf pack attacked and sank five transports at anchor in the harbor with survivors rescued by landing craft and treated on shore. The energetic work of Leonard Wood’s crew in landing the troops and rescuing survivors from the torpedoed transports resulted in a Legion of Merit award for Captain O’Neill. Battleship Massachusetts and cruisers Wichita, Tuscaloosa and Augusta, and Brooklyn prevented a breakout of the French warships allowing Leonard Wood to return safely to Norfolk, Virginia, with the invasion’s wounded soldiers.

After refitting and amphibious landing training at Solomons Island in Chesapeake Bay, the Leonard Wood departed for Mers-El-Kebir, North Africa. The ship was loaded with the 1,800 soldiers of the Army’s 45th Infantry Division. In port briefly, the ship conducted assault training for the troops, and then got underway with secret orders for the invasion of Sicily. On July 10, 1943, after a heavy Navy bombardment of the beaches near Gela and Scaglietti, Leonard Wood was ready for the assault. Poulin remembered German Stuka dive bombers attacking the anchored ships for hours at a time, and hearing their wailing dive brakes and whistling bombs falling on the U.S. fleet. Destroyer USS Maddox, on Leonard Wood’s port quarter, was struck by a bomb and sank only two minutes later.

At Sicily, with a heavy surf running, launching landing craft at night, and embarking the troops was a hazardous operation, so Poulin had to carefully operate a ship’s crane as quickly as possible to lower the landing craft. My father-in-law, Charles B. Cossaboom, was an Army private first class in the 45th Division, who vividly remembered the soldiers’ fear as they swung over Leonard Wood’s gunwale. They could see the LCVPs heaving in the waves and bashing the transport’s hull three stories below while climbing down the rope netting with 70-pound field packs strapped to their backs. He remembered seeing a friend lose his handhold, fall past the LCVPs, and leave the surface dragged to the bottom by the weight of his pack. Despite these losses, the dangerous work was completed in 20 minutes.

|

The night brought to the anchored ships attacks from the German Luftwaffe and a serious “friendly fire” incident. German codebreakers had correctly predicted an overflight of 82nd Airborne transports and arranged to have their bombers hitchhike at a lower altitude. Because the order was given to barrage fire, any aircraft crossing into designated sectors was subject to a wall of anti-aircraft fire from the fleet. Seven German planes were downed, but also 23 U.S. Army paratroop aircraft.

Poulin and Leonard Wood departed for Oran, Algeria, and loaded 766 German POWs for transport to the U.S. These prisoners were members of the German Army’s Afrika Korps and the Waffen SS’s Hermann Goering Division, who resisted any conciliatory gestures by Leonard Wood’s crew. Poulin remembered them as large, aggressive, front-line troops who were aloof, arrogant, and contemptuous of the U.S. crew. According to Poulin, the POWs were more shocked that they were defeated by “inferiors” than they were upset at being prisoners of war. Poulin was also surprised that Germans held religious services during their captivity in Leonard Wood’s hold. Like other U.S. military men, Poulin was taught that enemy troops were atheists.

PART II

After arriving in Norfolk, Leonard Wood was soon ordered to the Pacific. It sailed via the Panama Canal, arrived in San Francisco for refit and crew liberty before sailing for Honolulu. Poulin fondly remembered Leonard Wood arriving at the civilian Aloha Pier with serenading bands and hula girls, before the transport moved to a grim Pearl Harbor berth where sunken warships from the 1941 attack were still visible. All hands were called to load 14 railroad boxcars of provisions and the five boxcars of ammunition brought pier-side to stow on board Leonard Wood. Next, embarked 1,788 soldiers of the Army’s 165th Combat Team for the invasion of Makin Island.

At Makin, fighters and bombers from the fleet’s carriers leveled the island. Poulin remembered seeing not a tree standing. And he remembered that all Pacific invasions were carried out in broad daylight, rather than the pre-dawn assaults he had seen in the Atlantic theater. Japanese defenders retreated to underground bunkers to survive naval and air bombardments allowing troops to land on the beaches. These troops were subjected to day-and-night ambushes by an enemy that would go into hiding after their attacks.

After successfully landing the troops at Makin, Leonard Wood stood by to receive the wounded. These hospital cases came from shore and the aircraft carrier USS Liscombe Bay, which was torpedoed and sunk during operations. The transport returned to Pearl Harbor for refit and resupply. It reloaded with provisions, ammunition and 1,617 troops of the 3rd Battalion, 22nd Marine Division.

From Hawaii, the Leonard Wood sailed for Kwajalein for yet another amphibious operation. When battle wounded were brought aboard, Poulin was surprised that all casualties from the beach were taken to troop transports for medical attention rather than the hospital ships. He later learned there was a concern that marines with battle dressings and tourniquets might carry tropical infections that would jeopardize patients on board the hospital ships. Seeing marines with arms or legs missing and bloody bandages barely holding them together had a powerful effect on Poulin and his shipmates. The crew did their best to make the wounded comfortable until Leonard Wood’s doctors could attend to them. Turning the ship’s wardroom into a surgical center, the ship’s physicians had an enviable 100 percent survival rate--no one treated by them died.

When a surfaced U.S. submarine was strafed by Japanese aircraft, three sailors were killed, and the Navy sent out a request to the fleet for volunteers to transfer to replace the submariners. Poulin thought that it might be interesting to try submarine life and applied but was told that Coast Guard personnel were not welcome. Sea service cooperation had its limits.

Leonard Wood next participated in the Eniwetok invasion before returning to San Pedro, California, for refit and resupply. While in port, Coast Guard captain H.C. Perkins relieved Captain Merlin O’Neill as Commanding Officer.

Returning to the war zone, the Leonard Wood prepared for an assault on an undisclosed island. Soon after, the secret was blown by English language broadcasts of Tokyo Rose. Poulin remembered that her broadcasts were piped throughout the ship, since the crew enjoyed hearing the latest music from America. Between Glenn Miller and the Tommy Dorsey big band songs, Tokyo Rose expressed her “concern” for the brave Americans onboard Leonard Wood and named their Marine and Coast Guard officers, who were “on their way to certain death” at the hands of the Japanese defenders of Saipan. This radio reporting from the enemy failed to square with claims Poulin had heard that the Japanese were sub-human “monkeys” incapable of modern warfare.

At Saipan, the Japanese exacted a fearsome toll on the marines landed from the Leonard Wood, while the transports faced daily air attacks that forced them to get underway at 1600, maneuver all night and then return at 0600. One night, BMCM Poulin had to spend all night underway on his LCVP because the Leonard Wood got underway before he offloaded his cargo on the beach, and it was too dangerous for him to remain on the island. During the battle, hundreds of poorly trained Japanese pilots were shot down earning the air battle the name “Marianas Turkey Shoot”; however, there was a grislier event that Poulin recalled. In full sight of the crews on the anchored American transports, the Japanese Army prodded thousands of their civilian workers and their families out onto seaside cliffs, where they jumped to their deaths.

USS Leonard Wood returned to Pearl Harbor, where a ship’s inspection was conducted by the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet and Poulin literally bumped into Admiral Chester Nimitz when sliding down a ladder rushing to get to the chow line. He excused himself and avoided any repercussions. A month later, Leonard Wood joined the Palau Islands invasion fleet, and then loaded troops and supplies for the re-conquest of the Philippines. While operating off Leyte, the ship experienced heavy air attacks with two kamikaze planes missing Leonard Wood by 25 feet and struck a neighboring ship. The Japanese Navy launched a major offensive to destroy the U.S. troop transports and three Navy destroyers assigned to protect escort aircraft carriers and the transports sighted the Japanese battleships and cruisers. In a bold move, they turned towards the powerful Japanese fleet, attacking the much larger enemy ships with torpedoes before USS Johnston, USS Hoel and USS Samuel B. Roberts were sunk by the overwhelming Japanese firepower. This sacrificial effort startled Admiral Takeo Kurita on board the massive battleship Yamato, who considered it futile and suicidal to attack the now-empty troop transports in Leyte Gulf and ordered a retreat. Not expecting the Japanese fleet to turn back, Leonard Wood and the other undefended transports had slipped their anchor chains and steamed away quickly.

|

Returning to Manus Island for resupply and embarking marines, Leonard Wood was ordered to Lingayen Gulf and the invasion of the Philippine island of Luzon, where the capital city of Manila is located. The heavy escorting fleet sank two Japanese destroyers on the approach to the landing site, and Leonard Wood steamed back to the Manus Island base after landing the troops. While resupplying, a massive boiler explosion on Leonard Wood took her out of action and Poulin was ordered stateside, to the Explosive Ordnance Loading School in Baltimore, Maryland. During his three years on board Leonard Wood, he experienced nine major invasions, four smaller assaults, and his ship was credited with shooting down two German planes and three Japanese aircraft. Throughout the war, Leonard Wood never lost a crewman, even though she was subject to repeated air attacks in both war theaters.

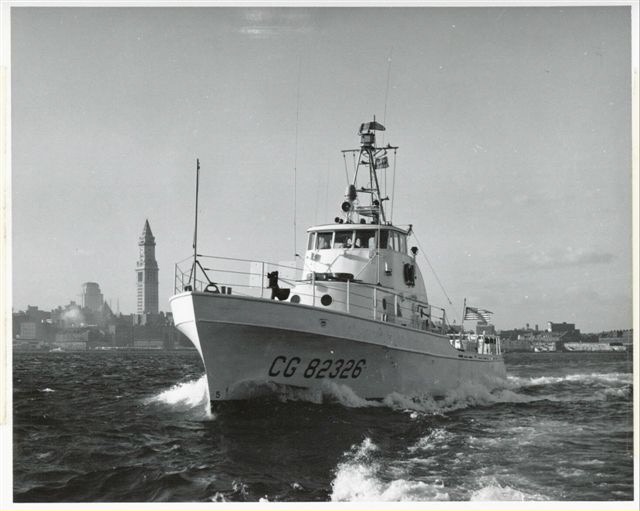

After discharge from the service, and two years of civilian life, Poulin returned to the Coast Guard in 1947 and was assigned to “handkerchief” Lightship 98. The skipper was a former merchant marine sailor who was fond of constructing ships-in-bottles when off duty, a craft that Poulin learned and enjoyed. One of his creations, a representation of USCGC Eagle, is displayed at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In later assignments, Poulin advanced to Boatswains Mate Chief while serving onboard CGC Casco, became Officer-in-Charge of Gay Head Lifeboat Station on Martha’s Vineyard, Deck Boatswain on board CGC Duane, Officer-in-Charge of Coast Guard Station Nahant, Massachusetts, and then Officer-in-Charge of CGC Point Cypress, where he and his crew rescued drowning fishermen and fought boat fires. During the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, Point Cypress was ordered to Florida, to patrol the Keys and Bahama Banks at a time when many Americans were concerned that a shooting war between the U.S. and the Soviet Union was imminent. A final duty assignment at the Marine Inspection Office in Boston followed and then on August 1, 1966, Master Chief Maurice Poulin retired from the Coast Guard. He and his wife Sylviane returned to their home in Nahant near their three children, six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. Master Chief Poulin passed away in April 2020. He was 97 years old.

-USCG-