Seaman Recruit John Cornelius “Jack” Cullen set out around midnight from the Amagansett, Long Island Coast Guard Station. It was Saturday, June 13, 1942, and Cullen, age 21, was just out of basic training. He had enlisted shortly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December. His job that night was beach patrol, and he left the station alone carrying only a flashlight and a flare gun.

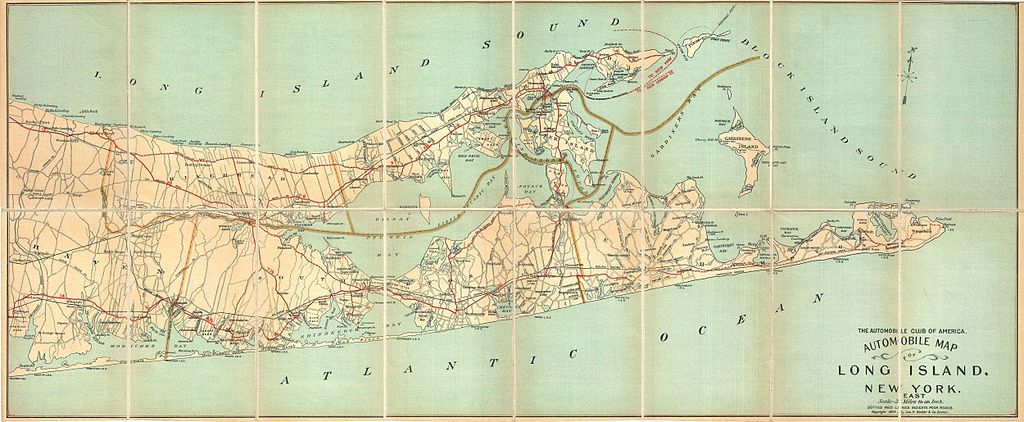

He started walking east toward the uninhabited tip of Long Island, about three miles away. Twenty minutes into his walk, barely 300 yards from the station, Cullen came upon a man clad in civilian clothes standing on the beach in the fog. As he approached the stranger, Cullen noticed two others in bathing suits standing knee deep in the surf.

Cullen called to the man, “What’s the trouble?”

All three men turned toward him, silent.

He called out again, “Who are you?”

The man in clothes advanced toward Cullen, who instinctively reached for the flashlight in his pocket.

Seeing Cullen reach for his hip, the man shouted over the surf, “Wait a minute. Are you Coast Guard?”

“Yes, who are you?”

With a slight accent, the stranger said, “We’re fishermen from Southampton and our boat’s run aground.”

“Come up to the station and wait for daybreak,” Cullen suggested.

The man responded, “Wait a minute—you don’t know what’s going on. How old are you? Have you a father and mother? I wouldn’t want to kill you.”

Just then, a fourth man waded out of the surf, dragging a heavy canvas bag. Unaware of Cullen, he started speaking to the others in German.

Cullen sensed something was going on. “What’s in the bag?”

“Clams. Yes, that’s right.”

Cullen had actually been born on Long Island, and he knew clams weren’t found in the area. But he said nothing.

“Why don’t you forget the whole thing?” the first man said. “Here’s some money—one hundred dollars.”

“I don’t want it.”

The man took out more bills. “Then take three hundred.”

Cullen thought it best to play along with the stranger’s offer. “Okay.”

“Now look me in the eyes.”

Cullen braced himself, fearing the man might try to hypnotize him.

“Would you recognize me if you saw me again?”

“No.”

The man repeated, “Would you recognize me if you saw me?”

“No,” Cullen assured him. “I never saw you before. I don’t know you.”

These were the last words exchanged between Cullen and George Dasch, leader of a team of Nazi saboteurs who had landed by U-boat at midnight that evening in June. Satisfied that Cullen wouldn’t tell anyone about the encounter, Dasch allowed Cullen to walk free into the night fog.

Cullen could not believe his luck. In an interview, he recounted that he “. . . backed-up most of the way. I didn’t trust them. I didn’t think I was going to get out of there.” He later remembered, “I went up the sand dunes, and I ran like hell for the station!”

After he made it to the station, Cullen told the officer-in-charge what had happened and showed him the wad of bills. Shocked, Boatswain’s Mate 2/c Carl Jenette responded, “Oh boy, this is big.” He immediately called the station commander and the local Coast Guard command. Jenette continued, “We’ll break-out some rifles. You don’t have to come back, but if you want to, go.” Cullen replied, “I’ll go.” Jenette armed the men with .30 caliber rifles, and then Cullen led them back to where he had seen the suspicious group of men.

By the time the Coast Guardsmen arrived at the scene, the Germans had departed. Cullen and his station-mates searched the beach and the adjacent dunes for any evidence of the enemy landing. At one point, they heard the U-boat and smell diesel fumes as it freed itself from the sandy shallows offshore. At 2 a.m., a local Army unit of 20 men joined them to assist in the search. By daybreak, the search party had dug up discarded German cigarettes, uniforms and swimsuits, and four wooden boxes containing explosives, equipment, false identity papers, and several thousand dollars in cash.

The Nazi team’s mission? To destroy U.S. infrastructure along the East Coast and cripple the American war effort at home.

Code-named “Operation Pastorius,” the team’s targets included aluminum factories, hydroelectric plants, automobile and railroad bridges, water reservoirs, canals and lock systems. The men were saboteurs donning no uniforms or identification. They were the first foreign combatants to step foot on U.S. soil in 130 years.

The day after the landing, Cullen became the subject of interrogations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He later recounted, “I was afraid the FBI thought I was somehow connected with the landing.” He continued, “Under ordinary circumstances, I should have been dead. They couldn’t understand why I hadn’t been killed . . . neither could I!”

With Cullen’s eyewitness account and his identification of George Dasch’s photograph, the FBI undertook a nationwide manhunt. Within two weeks, agents apprehended Dasch’s team plus a second four-man team that landed near Jacksonville, Fla.

The eight Nazis were tried by a secret military tribunal. Six were electrocuted and buried in unmarked graves in Washington, D.C. After providing information and evidence about the operation, Dasch and another saboteur were granted lengthy sentences rather than the death penalty. After the war, George Dasch and the other surviving saboteur were granted clemency and returned home to a divided Germany devastated by years of death and destruction.

Shortly after these landings, the FBI recommended establishing an armed beach patrol system. A month later, in July 1942, the Coast Guard launched the Beach Patrol, an armed coastal force serving out of Coast Guard bases and stations. The personnel patrolled beaches by horseback, jeeps and trucks. They were armed with sidearms, rifles, and automatic weapons; some teams also used canines. The system covered the East Coast, Gulf Coast and West Coast and became more sophisticated over time.

Jack Cullen received the Legion of Merit Medal for his role in uncovering Operation Pastorius. He was the first, and one of the only, enlisted men to receive the medal during World War II. The 1943 citation read in part, “His keen presence of mind and discerning judgment in a grave emergency undoubtedly prevented the successful culmination of hostile intrigue designed to sabotage our national war effort.”

The Coast Guard advanced Cullen from Seaman Recruit to Boatswain’s Mate 2/c and he participated in War Bond drives as one of the Coast Guard’s enlisted heroes.

Cullen left the Service in 1946 as a Boatswain’s Mate 1/c and began a career in Long Island’s local dairy industry. He later expressed regrets about leaving the Coast Guard rather than staying and advancing into senior enlisted ranks. He was one of the many Coast Guard heroes of World War II and the long blue line.

-USCG-