The Long Blue Line blog series has been publishing Coast Guard history essays for over 15 years. To access hundreds of these service stories, visit the Coast Guard Historian’s Office’s Long Blue Line online archives, located here: THE LONG BLUE LINE (uscg.mil)

Why was a retired Coast Guard Admiral speaking at the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of Rome during World War II? This was a question I was pleased to address when I was invited to a recent conference held in Anzio-Nettuno, Italy, to share the U.S. Coast Guard’s role as an element of the Allied Naval Forces in the Liberation of Rome campaign.

The event was sponsored by the non-profit Freedom for Italy organization and the Italian organization Assoknowledge to promote the memory of the Liberation of Italy by Allied forces in World War II. This groundbreaking event to commemorate the 80th anniversary was a big success, with 40 speakers and more than 150 delegates attending over the two days, providing valuable historical content and perspectives.

U.S. Coast Guard in World War II

At the time of World War II, the U.S. Coast Guard was the smallest of the U.S. Armed Forces. It operated as a joint force when called upon to protect the U.S. against threats both foreign and domestic, according to authorities, responsibilities, and tradition.

During World War II, the Coast Guard was transferred as a distinct organizational element into the U.S. Navy. This allowed Coast Guard personnel to continue many traditional missions associated with protecting the U.S. homeland while aligning under the U.S. Navy to support worldwide maritime missions. This organizational change remained in place until Jan. 1, 1946.

While newly aligned under the Department of the Navy, the Coast Guard still performed all its traditional domestic missions during the war. These included protecting ports, patrolling coasts to prevent sabotage and clandestine Axis threats, and overseeing the handling, loading, and shipment of much-needed war supplies flowing from the U.S. to support Allies in Europe.

The wartime missions demanded a rapid expansion of Coast Guard manpower. On Dec. 7, 1941, Coast Guard personnel, both military and civilian, totaled about 29,000. By June 30, 1944, the ranks had swelled to over 175,000 regular and reserve members. Additionally, in response to the great demand for Coast Guard personnel, Temporary Reservists were established — most of whom were volunteers serving part-time without pay. In June 1944, temporary reserve personnel actively enrolled reached over 51,000. The primary purpose of the temporary reserve was to release both active duty and regular reservists for duty at sea and in combat areas. Coast Guard missions were performed on land, on water, and in the air, taking advantage of new and evolving capabilities.

Many missions and capabilities were executed stateside and then projected into the transit zones of the Atlantic and the combat zones of the Mediterranean Theatre. Whether near the U.S. coastline, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, or amidst the intense battles in the Mediterranean theater, search and rescue operations at sea remained a top priority mission for the Coast Guard throughout World War II.

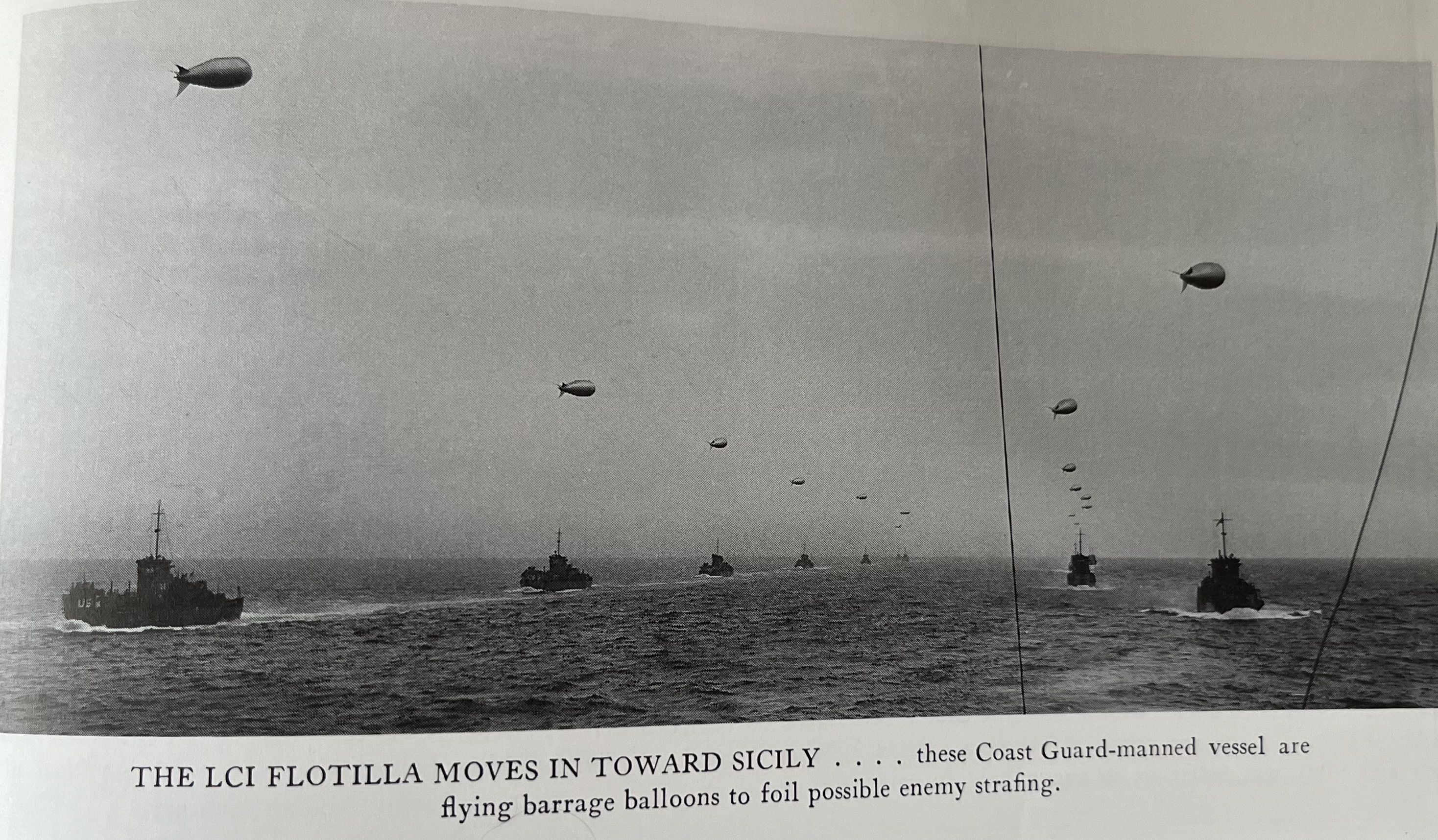

It is noteworthy that the Coast Guard participated in every amphibious operation by United States military forces during World War II. During the early stages of World War II, the major effort of the Coast Guard at sea was in the Atlantic. This began with the assignment of large cutters to Navy Task Forces for intensive escort-of-convoy duty and antisubmarine combat and continued with the landings in North Africa, Sicily, mainland Italy, and France, where the Coast Guard lent invaluable service to the Army and Navy.

|

As an example of how the Coast Guard expanded and adapted to greater responsibilities during World War II, at the start of the war, the Coast Guard had 168 vessels that were 100-feet or longer. By 1943, the total Coast Guard fleet comprised 802 vessels of 65-feet or longer, plus almost 8,000 smaller boats. In addition, Coast Guard personnel operated many Army and Navy vessels. In total, 351 Navy vessels and 288 Army craft were manned by Coast Guard personnel. This often blurred the role of Coast Guard personnel, overshadowed by the locations and wide variety of ship markings.

While many are familiar with the Allied landings in Normandy in June 1944, fewer know about the landings that took place several months prior in Italy. These were Operation HUSKY, the landing in Sicily on July 10, 1943; Operation AVALANCHE, the landing in the Gulf of Salerno on Sept. 9, 1943; and the final landing on Italian soil during World War II, codenamed Operation SHINGLE, on Jan. 22, 1944.

Operation SHINGLE

At the conclusion of Operation AVALANCHE, Allied leadership was optimistic that Rome might fall as early as late October 1943. These hopes rapidly diminished when it became clear that Axis forces planned to stubbornly contest the Allied advance from Salerno. Poor weather, mountainous terrain, and a series of east-west river crossings aided the German defenders, who slowed the Allied armies to a crawl up the Italian peninsula in the fall of 1943. By the end of the year, the Allies faced a stalemate at the Gustav Line, approximately halfway between Salerno and Rome.

In early November 1943, the overall Allied commander in Italy, British General Sir Harold Alexander, decided that another amphibious operation would be required to force the Germans from their position and open the road to Rome.

Dubbed “Shingle,” the operation was scheduled for the third week of January 1944. The plan called for landing the U.S. VI Corps under Major Gen. John Lucas at Anzio, approximately 80 miles behind the Gustav Line and 35 miles from Rome. The Anzio landings would be coupled with a breakthrough at the Gustav Line by the remainder of Lt. Gen. Mark Clark’s Fifth Army.

Joint U.S. – Royal Navy Task Force 81 (TF-81), commanded by Rear Adm. Frank Lowry, USN, provided the naval forces to support the landings. The task force — consisting of two headquarters ships, two submarines, four cruisers, 28 destroyers, 103 minor warships, other vessels, and 241 landing ships and craft — steamed from Naples on January 21st.

Notwithstanding the rehearsals a few days earlier, D-Day at Anzio went remarkably smoothly, aided by calm seas. Most enemy mines were cleared from the approach lanes despite the task force’s minesweepers having only a few hours to accomplish their mission. Enemy resistance onshore was virtually nonexistent, consisting mostly of sporadic artillery fire. Luftwaffe anti-shipping attacks were also light.

By the end of Anzio’s D-Day, over 36,000 men, 3,000 vehicles, and an initial stockpile of supplies — 90 percent of the initial assault load — had been delivered to the Anzio beachhead with light casualties. The operation had achieved total surprise. Task Force 81 continued to offload troops and supplies as VI Corps consolidated its beachhead.

Although caught off-guard during the first 24 hours of the operation, over the next several days, the Germans quickly concentrated troops in the region and stepped-up air attacks on the Anzio roadstead. However, the Luftwaffe proved unable to stop TF-81 from delivering troops and supplies onto the Anzio beachhead.

The naval task force’s mission at Anzio changed once the focus of the operation shifted to the fighting that raged around the beachhead. Much of the fighting took place beyond the range of Task Force 81’s guns. Maintaining a logistical lifeline became the critical role for Allied naval forces.

Helping Italy recover: A lesser-known Coast Guard initiative

Beginning with the Allied occupation of Italian territory starting in Sicily, it became immediately desirable to restore the country’s fishing industry. One lesser-known Allied initiative that engaged Coast Guard personnel was their involvement in supporting efforts to restore the Italian fisheries industry as combat moved north along the Italian mainland and the Allies established control.

Organizationally, Coast Guard fisheries experts were assigned to the Fisheries Division of the Agriculture Sub-Commission of the Allied Control Commission. The Allied Control Commission was an integrated British American body set up in September 1943 under the Supreme Allied Commander to enforce the Italian Armistice and to act as the body through which the Allied powers conducted business with the Italian government. In January 1944, the commission took over responsibility for military government when it absorbed Allied Military Government of Occupied Territories (AMGOT).

A Coast Guard mission was dispatched to Sicily in the fall of 1943 to assist in the work. In a sense, it was an extension of the service’s peacetime work, for the Coast Guard, as the maritime law enforcement agency, has long worked with the U.S. fishing industry in the fields of lifesaving, aids to navigation, and conservation. Their efforts were so successful that in the assigned territory, fishing activities were restored to approximately 75 percent of normal peacetime production despite material and manpower shortages.

Their mission proceeded in two phases. First, they found that the newly established Allied security regulations included blanket prohibitions against any Italian craft operating at sea. Their immediate job was to draft a framework of regulations that would meet the requirements of Allied naval security plans and still permit the freest possible operation of Italian fishing boats. Their goal was to draft a set of new regulations for the Italian fishing industry that would remain for restored Italian governance and enforcement agencies. By fitting the Italian fisheries regulations into the pre-existing framework and ensuring their original promulgation by the local Italian authorities, the new fishery regulations were being enforced by the new Italian government.

The second phase of the mission was outreach and personal engagement with Italian fishermen, port officials, and fish wholesalers to promote general awareness, understanding, and rehabilitation of the industry in coordination with local Italian Coast Guard authorities. The restoration of the fisheries industry was viewed as a win-win event, providing both an important food staple and jobs for those directly and indirectly involved in the Italian fisheries industry. In Sicily, there was a 400 percent increase in the number of fish coming into Palermo under the newly established organization compared to the same month of the preceding year when the fisheries were under Axis supervision. Like many of the Coast Guard’s current missions protecting natural resources, and working with the maritime industries and partner nations, this line of effort was very well received by all conference participants, especially our Italian hosts, as a little-known but critically important effort to help Italy begin to recover from World War II.

Honoring our fallen shipmate

The opportunity to participate in the Freedom for Italy conference commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of Rome was a unique chance to share the history of the U.S. Coast Guard’s role in supporting the Allied campaign and to learn about the many perspectives shared by our Italian hosts and representatives from other Allied participants. As the event was held in Anzio and Nettuno, Italy, it also provided an opportunity to visit the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, one of two American cemeteries in Italy memorializing the U.S. service members. Of the 1917 U.S. Coast Guard service members that made the ultimate sacrifice to help the Allies to victory in World War II, it was my honor to visit the Sicily-Rome American cemetery in Nettuno and pay tribute to a fallen shipmate interred in the beautiful cemetery — Steward Second Class James L. Hurt, U.S. Coast Guard.

-USCG-

[Author’s note: Participating in the conference was a great honor and profound experience to share one facet of U.S. Coast Guard’s history at a unique gathering in Anzio and celebrate the very relevant role of our U.S. Coast Guard missions during World War II. I’d like to extend my sincere thanks to the U.S. Coast Guard’s Atlantic Area Historian, William H. Thiesen, CDR Clay Pell, USCG, and CDR (ret.) Pat DiBari, USCG, for their assistance in preparing for this event.]