The Long Blue Line blog series has been publishing Coast Guard history essays for over 15 years. To access hundreds of these service stories, visit the Coast Guard Historian’s Office’s Long Blue Line online archives, located here: THE LONG BLUE LINE (uscg.mil)

In the summer of 1963, Lt. Bobby Wilks was flying an HU-16E amphibian aircraft on a regular patrol near the Cay Sol Banks. Temporarily attached to Air Station Miami, the mission was to search for Soviet Bloc ships headed toward Cuba. Aboard the USS Mills, a different drama was unfolding. A crewman was seriously ill and required evacuation by air. Wilks was rerouted to rendezvous with the destroyer.

Upon arrival, winds were estimated to be between 15 and 20 knots. Swells seemed acceptable for landing. However, a closer look showed two wave systems that crossed each other at 30 degrees, creating five-to ten-foot troughs. Wilks, however, noticed that the wake of the Mills calmed those waters. He then radioed the ship, explained the situation, and asked for their top speed. They answered, “27 knots,” and the lieutenant asked them to increase speed to 27 knots so he might observe the wake.

Contacting the District for permission to land, Wilks was told it was at his discretion. With flaps down 40 degrees, Wilks made his final approach. It was a rough landing, but he landed safely with no damage to the aircraft. Once the sailor was transferred, Wilks attempted to use the ship’s wake for takeoff. He was forced to abort his first attempt. He radioed Mills that he would try again. He told his co-pilot they would start with flaps at zero — a non-standard procedure. When he called for flaps, they would be set to 30 degrees and no more. This unconventional approach succeeded. The HU-16E rose in a shower of spray. Asking for flaps 30, the aircraft rose on a swell and into the air. It was nothing short of brilliant and still remembered today. Because of his skill, a life was saved. But who was this young pilot?

As America struggled with issues of racial inequality and segregation, African American Bobby C. Wilks was breaking barriers and blazing a trail for minorities.

As America struggled with issues of racial inequality and segregation, African American Bobby C. Wilks was breaking barriers and blazing a trail for minorities.

Born 12 May 1931 in St. Louis, Missouri, Wilks graduated from Sumner High School in 1947. After completing an associate degree from Stowe Teacher’s College, he was accepted into the U.S Naval Academy. Although he attended the Academy for a period of time, Wilks returned to Stowe to complete his Bachelor of Arts degree in education. There he excelled, participating in student choir, serving as senior class president as well as president of his fraternity and captain of the track team.

In 1954, Wilks completed his master’s degree at Saint Louis University. Earning a teaching certificate from the State of Missouri, he began teaching in the St. Louis Public School system. In 1955, he enlisted in the Coast Guard, divulging a juvenile and civil record of a “peace disturbance,” charges which were dropped in court. Wilks was ordered to the Officer Candidate School (OCS) program at the Coast Guard Academy, reporting on Oct. 15, 1955. He completed training on Feb. 28, 1956. Commissioned as an ensign, Wilks was assigned to duty at the Port of Baltimore. Shortly after his arrival, however, he received orders to flight training in Pensacola.

The officer evaluation report (OER) for the period of March through November 1956, speaks highly of the ensign’s capabilities:

ENS Wilks has performed his duties as a student naval aviator in a most satisfactory manner while attached to this command. He demonstrated exceptional ability as a student aviator in that he could grasp and retain fundamentals with relative ease. His spirit of cooperation and pleasing disposition aided him in group undertakings, His military bearing and neatness of dress are consistently excellent. ENS Wilks finished the U.S. Naval School, Pre-Flight Officer Indoctrination Course standing three in a course of 15 officers.

Coast Guard pilot and aviation historian, John “Bear” Moseley, attended flight school with Wilks. He stated that Wilks never spoke about his pioneering role in Coast Guard aviation, adding, “I do not know, of course, what was in his mind, but outwardly our goals were the same - to get our wings and be part of the best damn rescue service in the world.”

Designated Coast Guard Aviator No. 735 on March 22, 1957, Wilks completed training at Corpus Christi four months later and transferred to Coast Guard Air Station San Francisco. Promoted to Lieutenant, (j.g.), Wilks was ordered to helicopter training, and earned the designation of Coast Guard Helicopter Pilot No. 343 on Sept. 16, 1959. Six weeks later, Wilks was co-pilot in the rescue of U.S. Marine Captain Ray Lowe. The district commander received a letter from Lt. Col. Eldon Railsback, Marine Air Reserve Detachment, stating, “I wish to extend our warmest thanks to the United States Coast Guard and specifically to Lieutenant Commander J.E. Nesmith, LT B.C. Wilks, and Chief Petty Officer J.A. Accano for their efforts in rescuing him [Lowe] under adverse conditions. The Coast Guard aptly demonstrated that their motto, “Semper Paratus,” has more than poetic significance.”

Designated Coast Guard Aviator No. 735 on March 22, 1957, Wilks completed training at Corpus Christi four months later and transferred to Coast Guard Air Station San Francisco. Promoted to Lieutenant, (j.g.), Wilks was ordered to helicopter training, and earned the designation of Coast Guard Helicopter Pilot No. 343 on Sept. 16, 1959. Six weeks later, Wilks was co-pilot in the rescue of U.S. Marine Captain Ray Lowe. The district commander received a letter from Lt. Col. Eldon Railsback, Marine Air Reserve Detachment, stating, “I wish to extend our warmest thanks to the United States Coast Guard and specifically to Lieutenant Commander J.E. Nesmith, LT B.C. Wilks, and Chief Petty Officer J.A. Accano for their efforts in rescuing him [Lowe] under adverse conditions. The Coast Guard aptly demonstrated that their motto, “Semper Paratus,” has more than poetic significance.”

On July 15, 1960, Wilks was transferred from the Reserves to the Regular Coast Guard. He was subsequently assigned to Coast Guard Air Detachment Sangley Point, Republic of the Philippines, piloting aircraft on search and rescue missions as well as logistics and resupply missions to Coast Guard LORAN stations. He also served as Head of the Administrative Section for Commander Philippine Section, and the Air Detachment.

In the person of Lt. Bobby Wilks, the Coast Guard found a unique representative. His fitness reports were outstanding. He was both a skilled aviator and educator. His already impressive credentials led to a new opportunity. In September 1961, Wilks was assigned to Coast Guard Headquarters for a unique mission. Coast Guard leadership announced that Wilks would undertake a recruiting mission, speaking with civic leaders and high school officials in an effort to recruit minorities into the Coast Guard Academy. Over a period of seven months, Wilks traveled extensively, speaking about the opportunities presented by attending the Academy, stating:

The Coast Guard Academy, located in New London, Connecticut, is similar to the other government Academies … but with this important difference ... candidates are selected from a nationwide competitive examination … no political appointments are required, no geographical quotas are prescribed. At the Academy you will take a course of study much like that of a top-flight college. You will study both Engineering and Liberal Arts subjects needed in your Coast Guard career such as law, seamanship, navigation, and gunnery. It costs no money to attend the Academy. All it really costs a cadet is the time and energy to devote to his studies there.

Lt. Wilks added five points he felt of importance, points that exemplify his service:

- The Coast Guard does NOT offer you a free education, with pay without obligation on your part. The Coast Guard Does offer you an excellent education, with pay, plus a lifetime career in the service of your country and humanity.

- The Academy does NOT offer you the happy-go-lucky type of life often associated with college.

- The Academy does NOT offer an easy curriculum. Good things don’t come easily. We have to WORK for them.

- The Academy does NOT offer you immunization against menial work. You learn by doing.

- Cruises offer you NONE of the features of a travel tour. They can be tough and sometimes grueling. But is the spirit of adventure dead in you boys? It is because it is rough that it develops skill and courage and seamanship ability of a high order.

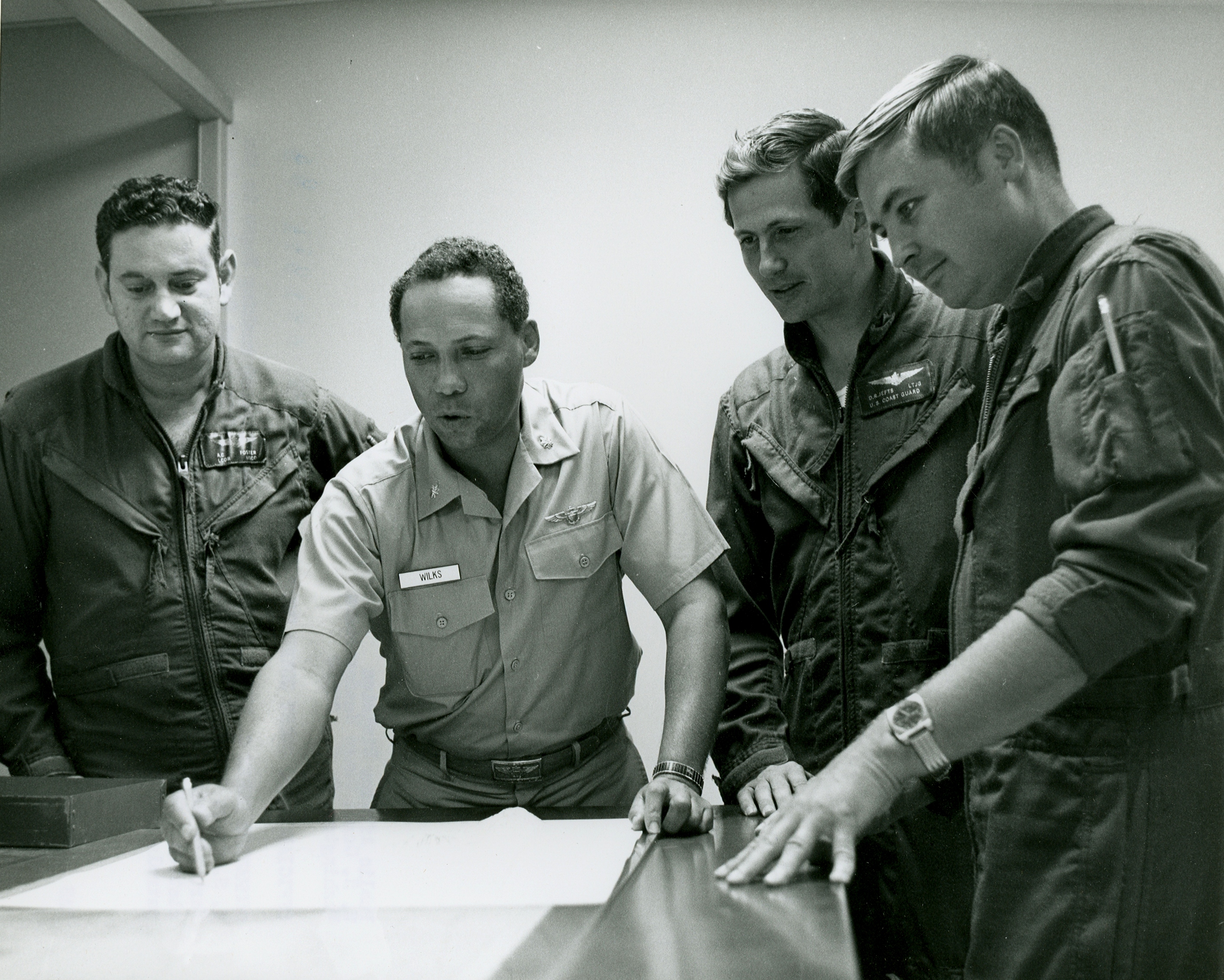

Recognized for his “keen insight relative to the delicacy of the assignment,” Wilks was congratulated by senior leadership, and subsequently recommended for promotion. In March 1962, he was assigned to Coast Guard Air Station Brooklyn, as aviator and Senior Operations Officer. A fitness report covering the period between October 1962 and March 1963 specifically mentions that Wilks, “has been employed by the Commandant on several occasions in connection with Cadet Procurement and speaking engagements,” in addition to being “a very competent helicopter and fixed wing pilot.” During this three-year tour, Wilks was temporarily assigned to Air Station Miami. He executed the USS Mills rescue, flying an HU-16E “Albatross,” and rescued three men trapped in the Everglades.

In March 1965, Lt. Wilks was assigned to Coast Guard Air Station Naples, Italy, serving as pilot and executive officer. Four months later, he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander, the first recognized African American to surpass the rank of lieutenant. He was judged to be:

… a forceful and effective executive officer … well-informed of the station’s operations. His opinions are respected and his advice is often sought by other officers. He is an excellent aviator with considerable natural ability and good judgement.

It was also noted that he took “his social responsibilities seriously…in an effort to maintain the excellent relations and cooperation the unit has enjoyed with the local Navy command.”

Quite obviously, over the course of the first 13 years of his career, Wilks was credited for his abilities in the cockpit and as a leader. Said aviator Dallas Schmidt, “He was one hell of a stick and rudder pilot.” John “Bear” Moseley too, praised Wilks’ abilities, stating, “He pushed the envelope to its very limits, and his skill brought men and machine home.”

With the exception of his fitness reports while working to recruit African Americans into the Coast Guard Academy, his race was not mentioned. Other contemporaries have stated it was not an issue, at least not publicly. That changed in August 1968 when Wilks was assigned to Air Station Salem in Massachusetts. For the first time in his career, his fitness report questioned his abilities, and indicated that issues were caused by the color of his skin:

Mr. Wilks is the only negro Coast Guard aviator. Consequently, he is frequently utilized as a showpiece by CG Headquarters. He has adapted well to his subspecialty of flight safety and produces excellent written reports. Like most FSOs he is somewhat frustrated by the opposing demands of flight safety and the basic SAR readiness mission as postulated by the Coast Guard. His opportunities to innovate are limited. Socially, he is a good mixer, but understandably reserved.

His next fitness report proved no better. His OER for the period of Feb. 1, 1969, through July 31, 1969, described Wilks as:

...solid, but undistinguished. His areas of weakness are in the execution of his ideas and the carrying out of his military duties. He will indicate an area of weakness in safety or another pilot’s technique, but fails to follow through and endeavor to obtain compliance. This same trait is sometimes evident in his watchstanding in that he will accept marginal performance from his subordinates.

This, very clearly, is different from his past performance evaluations.

Despite these unfavorable reports, Wilks continued to excel and, on the night of Oct. 8, 1969, launched a search and rescue mission. A student pilot was flying from Providence, Rhode Island, to Taunton, Massachusetts, when he became disoriented. Wilks located the lost aircraft over the Atlantic with fuel running low and guided the student pilot to shore and a safe landing with five minutes of fuel remaining. On Feb. 19, 1970, Wilks was awarded the Federal Aviation Association’s “We Protect with Pride” plaque for the rescue. Interestingly enough, his third and final fitness report at Salem was drastically different than the first two, describing Wilks as:

...a very fine flight safety officer. His written reports have continued to be very excellent and his obvious sincerety [sic] in the program further enhance his performance. It is always a pleasure to see someone develop to a level that is commensurate with his potential, and in this officer, I have seen just that. All in all, an excellent officer, one of the best of his rank presently attached.

Several years later, Wilks spoke about these unfavorable reports with a young RM2 Vincent W. Patton, who later became the first African American Master Chief Petty Officer of the Coast Guard. Said Patton, “Capt. Wilks mentioned how, at times, he was referred to by his color during his evaluations. It wasn’t meant to be positive, at least that’s how he put it to me.” Patton added that Capt. Wilks told him, “How he had to deal with a CO, and XO that weren’t very happy with his somewhat ‘celebrity status’ as being the senior most African American officer at the time. However, Wilks brushed off the comments/complaints, and saw it as an opportunity to helping others…”

|

|

Photo of Commander Wilks, who served as aviator and Operations Officer at Air Station Barber’s Point, Hawaii. (U.S. Coast Guard)

|

In September 1970, Wilks reported to Air Station Barber’s Point, Hawaii, to serve as aviator and chief of operations. On the night of Dec. 9, 1971, the master of a Soviet vessel, located some 116 miles east of Hilo, Hawaii, suffered a heart attack. In gale force conditions, Wilks launched his HH-52A for a medical evacuation. He departed Barber’s Point, encountering strong and steady headwinds enroute to Hilo for refueling. His attempt to rendezvous with the ship was aborted when the Soviet vessel could not be located. While returning to Hilo, Wilks was made aware that the ship was actually 40 miles beyond the operating range of the aircraft.

Despite the dangerous weather conditions, a second attempt was made. The vessel was located, pitching 30 to 40 feet vertically, and rolling heavily. Hindered by heavy salt spray and a language barrier, Wilks persevered, successfully hoisting the stricken mariner. He was later awarded the Air Medal for this mission. Wilks was also twice recognized with the Sikorsky Winged “S” Award, awarded for noteworthy rescues with a helicopter, receiving praise as both an officer and leader, as well as a fine pilot.

From September 1975 through July 1977, Cmdr. Wilks served as Executive Officer at Base Governor’s Island, New York. He once confided to a friend that he felt his assignment to the facility was part of an effort to curb racial tensions on the island. That is supported in a report written by Capt. C.J. Glass, who stated that he “had the benefit of his [Wilks] views on racial issues on Governor’s Island and in the Coast Guard in general.” Glass believed that while Wilks would be an excellent choice for an air station commander, he felt that his unique experiences would be of great value in other capacities and recommended that he had excellent potential as a Group Commander. In August 1975, Wilks assumed the role of Chief, Search and Rescue Branch, Coast Guard District Three. Glass later wrote that Wilks was “presently the senior minority Black member of the Coast Guard. In this capacity, I think the Coast Guard could not hope for a better model of success. He has justifiable pride in his accomplishments and a firm conviction that success comes to those who work for it.”

Master Chief Patton recalled meeting Wilks for the first time:

I had the honor of first meeting him in '76, just before I went on recruiting duty in Chicago. He was a commander at the time. It was interesting to note that he was the senior ranking African American officer at that time. He was an average size man, but to me, he was bigger than life itself. I was in awe of him, as not only he was the first senior ranking African American officer at that time, but also an aviator. I hung on to every word he said to me, as we talked about goals and vision. He shared with me the challenges, which he was quick to call them opportunities, that he took full advantage of that mapped out his successful Coast Guard career at that time.

In September 1977, while serving as Chief, Boating Safety Division, Coast Guard District Fourteen, Wilks was promoted to the rank of captain. Two years later, Capt. Wilks took command of Coast Guard Air Station, Brooklyn, becoming the first minority officer to command an air station. He subsequently earned the Coast Guard Commendation Medal for outstanding service.

Capt. Wilks final assignment during his Coast Guard career was Liaison Officer, Staff Assistant for Search and Rescue with the Federal Aviation Administration. There, he was a member of the team that developed the Rotorcraft Master Plan, a document used by the FAA to integrate the helicopter into the National Airspace System. His final OER states, “Captain Wilks is an absolutely outstanding officer.”

In 1986, Captain Bobby Wilks retired from the service after a career that spanned 31 years. Over the course of that career, he accumulated over 6,000 hours of flight time, and was qualified to fly 20 different aircraft. More importantly, Wilks smashed racial barriers and, through his leadership and example, led the Coast Guard to greater diversity. He mentored future leaders like Master Chief Patton, and Admirals Errol Brown and Manson Brown.

Capt. Wilks passed away in 2009, at the age of 78. When his wife, Aida, called his longtime friend, retired Cmdr. Dallas Schmidt, to deliver the sad news, she added that the last words spoken by Capt. Wilks were of his friend. Schmidt asked, “The beers I owed him?” “No,” replied Mrs. Wilks, “Dallas let me fly under the Brooklyn Bridge.” Despite his remarkable career, it was a poignant memory of flying with a friend that formed his final words.

Capt. Wilks was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery with friends, those he mentored and served with, and Coast Guard leadership in attendance. Today, his legacy continues to inspire those who choose to serve and continue the long blue line.

-USCG-