Most of the rescue missions carried out by the United States Coast Guard and its predecessor agencies (i.e., the U.S. Life-Saving Service, U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, and U.S. Lighthouse Service) were typically associated with marine accidents involving ships or boats. In contrast, the Coast Guard response to the 1939 accidental sinking of the Navy submarine USS Squalus (SS-192) is unique.

Accidental Sinking of the USS Squalus

On the morning of May 23, 1939, the American Sargo-class submarine Squalus was underway for trial maneuvers and dives off the coast of New Hampshire near Isle of Shoals. Earlier test dives had been conducted successfully, and there were no indications of any mechanical or equipment problems.

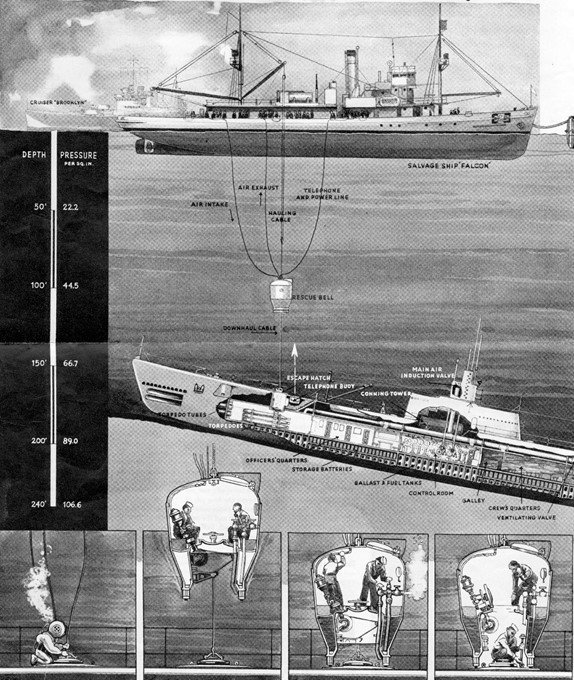

With a crew of 56 officers and sailors plus three civilian technicians, Squalus commenced a routine dive at 7:40 a.m. Within minutes, the sub experienced catastrophic flooding of the engine rooms, crew’s berthing compartment, and the after torpedo room due to a faulty main induction valve (which allows outside air to enter for diesel engine operation) that did not close properly prior to the dive.

Despite determined efforts to return to the surface, the submarine sank stern-first to 240 feet and sat on the seafloor about nearly four nautical miles south of Isle of Shoals. Immediately releasing a marker buoy with telephone line to the surface, the survivors attempted to signal any nearby ships by means of flares and smoke bombs floated to the surface. Trapped and tragically drowned in the flooded after compartments were 24 officers and sailors plus two civilian technicians. This left 32 officers and sailors and one civilian technician alive in the unflooded forward compartments.

Fortunately, Squalus’s sister submarine, USS Sculpin, was in the vicinity. After being alerted by the naval shipyard that the Squalus was overdue and missing, Sculpin commenced searching and found the marker buoy in the afternoon. After establishing telephone contact with the crew of the Squalus, communications were lost when the marker buoy cable was accidentally severed. Squalus was relocated a few hours later using Sculpin’s sonar gear and a drag hook deployed from the Naval Shipyard tugboat Penacook. From the dragline, a new marker buoy was placed over the Squalus.

Responding Units of the Coast Guard

The Coast Guard’s District One in Boston ordered all available units to proceed immediately to the scene. The first to arrive that evening was Station Isle of Shoals’ picket boat CG-991, which was a powerful ex-rumrunner capable of greater speed than the other available Coast Guard vessels. The boat brought out the first Navy deep-sea divers available in the area from the naval shipyard (two divers, two dive tenders, two mechanics, and their diving equipment). Shortly thereafter, patrol boat CG-158 arrived from its homeport of Gloucester, Massachusetts. Motor lifeboats from Stations Isle of Shoals (CG-4409/CG36382), Portsmouth Harbor (CG-5170/CG36436) and Merrimac River (CG-5139/CG36424) also arrived, along with motorboats CG-5549 and CG43010 from Isle of Shoals. By late evening, patrol boat CG-409 arrived, carrying key personnel and equipment from the Navy’s Experimental Diving Unit, who had flown to Portsmouth from their base in Washington, D.C. And, shortly after midnight on May 24th, cutter CGC Harriet Lane arrived, along with the Lighthouse Service tender Hibiscus.

The Coast Guard vessels and boats were tasked with maintaining a safety cordon around the site. These craft searched for Squalus survivors that might have individually ascended to the surface, while keeping smallboats carrying photographers, reporters, and spectators at a safe distance. The larger Coast Guard picket boats and cutters ferried key personnel and equipment from the naval shipyard to the wreck site. Along with the Hibiscus, they were also used to assist the Falcon and Wandank to set out four-point mooring anchors, lines, and buoys. These were used to position the Falcon directly over the Squalus to carry out dive and rescue operations.

Rescue of Squalus Survivors

The only hope for rescuing the Squalus survivors lay with the recently developed, but never used, McCann Submarine Rescue Chamber (SRC). The only SRC available on the East Coast was aboard the submarine rescue ship Falcon, which fortunately was in port at New London, Connecticut, and quickly arrived on scene. This would be the first use of an SRC for a rescue mission.

With two operators, the SRC descended to the stricken submarine’s escape hatch located in the submarine’s forward torpedo room. Once seated over the hatch with a watertight rubber seal, the SRC’s hatch could be opened. After the submarine’s escape hatch was opened up the eight survivors could be brought into the SRC. After closing the hatches, the watertight seal could be broken and the SRC’s ballast blown, the SRC could float to the surface.

One of the challenges facing the Squalus rescue was the 240-foot depth. At that depth, deep-sea divers using surface-supplied air could only remain on the bottom 20 minutes before risking nitrogen narcosis. However, the Navy’s Experimental Dive Unit had developed deep-sea diving techniques using a helium-oxygen mixed gas and specialized equipment for this technique.

Time was critical for rescuing the survivors before the submarine’s remaining oxygen was exhausted. Once securely anchored over the Squalus, the Falcon commenced dive operations and use of the SRC. Over a period of 14 hours, four trips down were made by the SRC, rescuing 33 survivors. A fifth trip was made to the Squalus’s after torpedo room hatch to verify that no men had survived in the flooded portion of the submarine.

Once brought to the surface, the survivors were transferred to Coast Guard Cutter Harriet Lane for return to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. This allowed the Navy vessels to remain on scene for the more difficult, challenging, and time-consuming raising and salvage of the Squalus.

Post-Rescue Raising/Salvage Operations

The raising and salvage of the Squalus was one of the most challenging diving and salvage operations ever conducted by the Navy. Today, the final report of this operation is included in the Navy’s salvage handbook.

To raise the Squalus, several floodable salvage pontoons with chain bridles were placed under the bow and stern of the submarine. Once in place, the pontoons were filled with air from the surface with air pressurization hoses. The inflated pontoons provided the buoyancy necessary to lift the submarine off the seafloor and up to the surface. Rigging these pontoons required extensive diving operations, most of which were carried out using the new mixed helium-oxygen gas methods.

Much of this effort was initially trial and error, with the first raising attempt resulting in a spectacular failure consisting of the Squalus rising uncontrolled to the surface, slipping out of the chain bridles, and falling back to the bottom. It took four months (from late May to mid-September 1939) and five attempts to complete the raising and towing of the Squalus from its wreck site back to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard. During these attempts, once again, the CGC Hibiscus — along with picket boat CG-991 and other Coast Guard small craft — aided with salvage moorings, towing and safety cordon patrolling. Ultimately, the Squalus was repaired and recommissioned as the USS Sailfish, which had a successful World War II career.

The Coast Guard has, on many occasions, successfully assisted in very different and unique types of rescue missions over its history, including those involving Navy vessels and units. Although the Navy served in the primary role of rescuer and salvager, the Coast Guard provided important assistance that has never been fully related. Although not equipped and trained to carry out underwater rescue operations, the Coast Guard can provide critical assistance in these types of operations, and certainly shared in the success of those efforts for the Squalus rescue.