On March 17, 1924, four United States Army aircraft — Seattle, Chicago, Boston, and New Orleans — took off from Santa Monica, California, for Seattle, Washington. It was the first attempt to circumnavigate the globe, and the world was watching through newspaper accounts. The trip took 175 days, 363 flying hours and covered some 26,000 miles with landings in 22 countries. All the planes were specially built, open cockpit, 38-foot Douglas World Cruisers. On April 6, the planes left Seattle, heading toward Alaska. Seattle, the lead aircraft, was flown by Maj. Frederick L. Martin, with Staff Sgt. Alva Harvey on board as the flight mechanic. Following this flight from the ground was the Coast Guard cutter Algonquin, which provided parts, rest breaks, meals, and fellowship for the two men. The cutter was on its annual Alaskan cruise from April through November 1924.

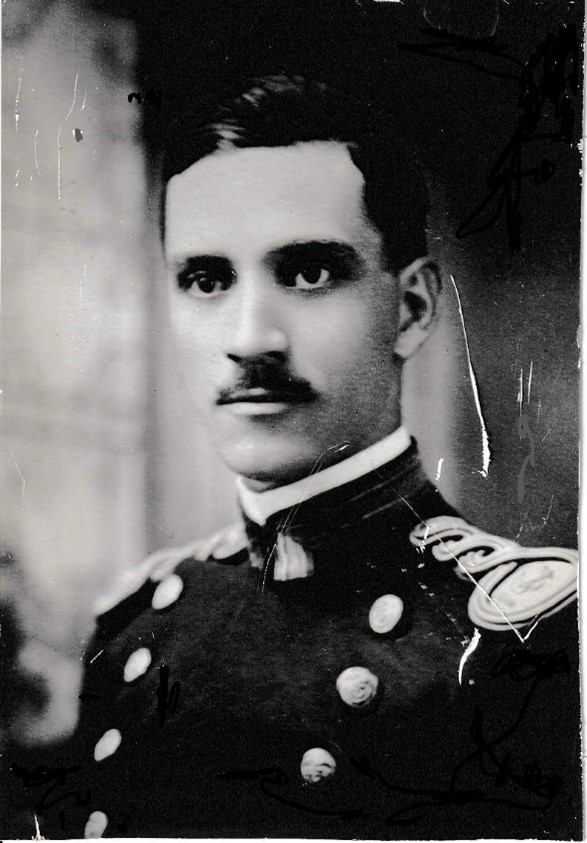

The crew of Algonquin became quite close to Martin. In the Special Collections of the Coast Guard Historian’s Office are letters that Lt. William Pitts Wishaar, the executive officer of Algonquin, wrote to his wife, Elise, from 1924 to 1925.

Background

Born at sea off the Mexican coast on December 6, 1886, Wishaar’s father was a newspaperman and Civil War veteran. By the time he took the examination for entry into the Revenue Cutter Service in 1906, he was an architectural draughtsman. He was accepted as a cadet by the service and received training on board the training ship Chase at New London, Connecticut.

Between 1910 and 1916, Wishaar underwent explosives and wrecking operations training, along with electrical and radio/telegraphy training. He also qualified as a diver in 1911. In April 1916, he requested aviation instruction, but it was delayed because of World War I. The following summer, Wishaar was assigned to the Manning and requested duty in European waters. He spent the war as a navigation and gunnery officer, putting in 16-hour days under steady strain and high pressure, and seeing firsthand the horrors of war at sea, which contributed later to post-traumatic stress.

In the fall of 1918, when he returned home, Wishaar was 32 years old and putting in 16-hour days at the Revenue Cutter Service School of Instruction as a radio instructor. Simultaneously, Wishaar studied very hard for aviation training. Finally, on September 29, 1919, Wishaar reported for aviation instruction at Pensacola, Florida, where he completed training in heavier-than-air flying craft. On June 23, 1920, Wishaar’s plane caught fire during spotting training off Santa Rosa Island, Florida. The plane made a forced water landing, and Wishaar and the other two men on board swam 15 minutes before being rescued. The plane was destroyed. Nevertheless, he graduated first in his class, was appointed Coast Guard Aviator #5 on November 17, 1920, and became executive officer of Coast Guard Aviation Station Morehead City, North Carolina. Not even a year later, on July 1, 1921, the air station went into an inactive status.

In the fall of 1918, when he returned home, Wishaar was 32 years old and putting in 16-hour days at the Revenue Cutter Service School of Instruction as a radio instructor. Simultaneously, Wishaar studied very hard for aviation training. Finally, on September 29, 1919, Wishaar reported for aviation instruction at Pensacola, Florida, where he completed training in heavier-than-air flying craft. On June 23, 1920, Wishaar’s plane caught fire during spotting training off Santa Rosa Island, Florida. The plane made a forced water landing, and Wishaar and the other two men on board swam 15 minutes before being rescued. The plane was destroyed. Nevertheless, he graduated first in his class, was appointed Coast Guard Aviator #5 on November 17, 1920, and became executive officer of Coast Guard Aviation Station Morehead City, North Carolina. Not even a year later, on July 1, 1921, the air station went into an inactive status.

With the closing of the Coast Guard’s aviation program in 1922 due to demobilization, Wishaar returned to sea duty onboard Yamacraw. In March of that year, when asked what his preferred duty was, Wishaar put down “aviation or administrative duty.” He had no desire to return to sea duty but had no preference once he was back at sea.

Wishaar was diagnosed with neurasthenia in 1923, a condition defined chiefly with emotional disturbance or nervousness, which is how his doctors termed it. By March 1926, Wishaar was convinced that any further sea duty would lead to a nervous breakdown. At the advice of his doctors, Wishaar retired from the Coast Guard in July 1926 on medical disability, following service on board Algonquin and Bear. Yet, in his letters to his wife, he never even hinted at any such disturbances other than the occasional insomnia. They are full of adventure and excitement as he recounted the search for a downed plane and missing pilot.

The Army’s Around the World Flight and Algonquin

The four planes initially took off from Sandpoint Flying Field in Seattle on April 6, 1924. Shortly after departing Prince Rupert Island on April 15, Seattle blew a three-inch hole in its crankcase and was forced to land in Portage Bay. Algonquin’s crew had a replacement engine ready and even assisted with repairs. Seattle resumed its journey on April 25, attempting to catch up with the other three planes. Five days later, on April 30, in a blanket of heavy fog and during a time when aircraft were not equipped with radio or radar, Seattle crashed into a mountain near Port Moller.

Wishaar described Alaskan weather to his wife in an April 21 letter:

To comprehend it, or visualize it, or get any conceptions of its bleakness and austerity and sternness, you must first of all read this letter on the back veranda on a cold night (temperature 15 degrees F) clad only in your thinnest, and have a sirocco 100 horsepower blower-fan, cooled to the nth degree, blowing directly at you from all gusty angles. It just can’t be described. It must be felt.

Onboard Algonquin was newspaperman Evan David. Wishaar found David to be an “exceptionally interesting and well-read man,” who was Harvard-educated and a seasoned world traveler. Thawing out over a stove onboard Algonquin, Martin regaled Wishaar, Capt. Cecil Gabbett and his son Cecil, and David with stories of his journey in the Seattle. Wishaar’s wife would read these stories in local papers before his letters reached her some three weeks later.

Wishaar pointed out that the flight was the main reason why the Algonquin was “in this rugged, bleak, austere, bitter country at this season.” Even though it was April, it was bitterly cold in the 20-degree range and there were no trees to be seen. On April 17, Wishaar wrote that Martin was in “some little town – just north of Kodiak Island.” Algonquin was to take onboard a spare plane motor and other parts and proceed to that point.

Algonquin’s crew likely had the highest regard and admiration for Martin. Wishaar wrote on April 17, “I take off my hat to these fliers, they have ‘guts’ and nerve and daring and a taste for out-of-the-ordinary-methods-of-dying that place them in the ranks of He-men of the first magnitude.”

By April 28, at Kanatak, Alaska, Martin was still unable to repair his plane on account of bad weather. The plane was boarded up with wood to prevent the wind from picking it up and anchored to a buoy in the harbor, but the spray of the waves froze into masses of ice. Martin was already two weeks behind his squadron and was given two days to catch up at Unalaska. Flying to Chignik, the next stop on the route, would increase the chance of losing his way or even crashing into the rocky shores. Returning to Kanatak to await more favorable weather would take him “out of the race.”

Alaska was mostly unchartered territory in the 1920s. Algonquin had onboard inaccurate charts of the region that did not show all of its landmarks. Captain Gabbett had to rely on his memory for nearly every square foot of the shoreline as seen from the cutter. The flight from Kanatak to Chignik normally took two hours over 115 miles. It took Martin four hours to fly 90 miles from Kanatak to Kujulik Bay, where he landed to rest and find out where he was. It was a little over twenty miles from Kujulik Bay to Chignik so, after an hour’s rest, Martin took off again. Due to the low visibility, the last leg of the flight took much longer than anticipated, but Martin arrived in Chignik safely. Two salmon canneries operated at Chignik in the summer, so there was no one there when Martin arrived.

Meanwhile, onboard Algonquin, tensions ran high as the crew awaited word of Martin’s safe arrival in Chignik. Algonquin had left supplies and repair materials at a temporary Army radio station at Chignik, staffed by a single Army sergeant. Algonquin’s only means of communication with Martin was through this sergeant. Finally, at 6:30 p.m., the cutter’s radio cackled with news of Martin’s safe landing, an hour after he had arrived. At this point, Algonquin was enroute to King Cove, some 190 miles westward, to await the passing over of Seattle on its way to Unalaska.

At 11 o’clock on the morning of April 30, Seattle took off for Unalaska once again in bad weather. Previously, plane repairs sometimes took all night in bad weather, and men from Algonquin assisted whenever they could be spared. As the crew watched Seattle take off, one can imagine their thoughts as their eyes looked skyward. For the rest of the day, however, Seattle did not pass over Algonquin, and there was no news of its safe arrival in Unalaska. The crew began to fear the worst as time passed and there was no word.

Algonquin had expected to get a radio message from the Army sergeant two to three hours after Martin had taken off. Algonquin’s crew returned to the cutter; there were so many men ashore that their large surfboat could not return them in a single trip. As the day wore on with no word about Martin, the crew began to lose its morale, yet still Algonquin ploughed along full speed through the snow. Around 8:00 p.m., word arrived that Martin had landed at Chignik about three hours earlier. Wishaar described the scene to Elise in an undated letter:

Six hours flying in the air flying a little over 100 miles! You can imagine how relieved we felt . . . I cannot tell you how my feelings were – all mixed up with admiration over his pluck and nerve and daring; fear of him flying in a snow storm over a very dangerous territory, where if his motor failed a forced landing in the sea on the rocky coast would mean the loss of the plane and very possibly death for Harvey and himself; and also a sort of anger his taking such dam fool risks.

Crash of the Seattle and Survival

Wishaar’s next letter, dated May 1, opened with a single sentence — “Major Martin is ‘down’ somewhere.” Seattle had crashed into a mountain on April 30, but, miraculously, Martin and Harvey walked away with minor injuries. It took them ten days on foot to reach the town of Port Moller, Alaska. It was six days before they found suitable shelter, where they rested for four days. Starting out again on May 10, they reached Port Moller the same day and were rescued by cannery employees. Meanwhile, Algonquin’s crew was on pins and needles awaiting word of Martin’s safe arrival at Unalaska. According to Wishaar’s May 1 letter, when there still was no news by the next morning, “Captain Gabbett took Algonquin full speed into bays and inlets hat he or nobody else on board knew anything of and that had no surveys and charts made of them. Such work, in this country of unchartered dangers and unknown parts was a very fine exhibition of nerve.”

Wishaar’s next letter, dated May 1, opened with a single sentence — “Major Martin is ‘down’ somewhere.” Seattle had crashed into a mountain on April 30, but, miraculously, Martin and Harvey walked away with minor injuries. It took them ten days on foot to reach the town of Port Moller, Alaska. It was six days before they found suitable shelter, where they rested for four days. Starting out again on May 10, they reached Port Moller the same day and were rescued by cannery employees. Meanwhile, Algonquin’s crew was on pins and needles awaiting word of Martin’s safe arrival at Unalaska. According to Wishaar’s May 1 letter, when there still was no news by the next morning, “Captain Gabbett took Algonquin full speed into bays and inlets hat he or nobody else on board knew anything of and that had no surveys and charts made of them. Such work, in this country of unchartered dangers and unknown parts was a very fine exhibition of nerve.”

Wishaar had two theories of what had happened to Martin. One was that heavy winds caused Martin’s plane to crash or sink. The other was that the plane had crashed, but Martin and Harvey had survived and obtained shelter with no way to radio for help. Another Coast Guard cutter, Haida, was ordered to assist in the search for the downed plane. Wishaar’s feelings are further documented in his May 1 letter:

With no definite word as to where he was last seen, it is almost like hunting for a needle in a haystack in this country of vast distances and thin population. We have great faith though in Martin’s resourcefulness and ability to pull through whatever difficulty he has got into. The thought that he may now be drowned, may be dead of a crash, may be lying badly smashed and suffering someplace on land, are depressing, and we try to be as optimistic as possible hoping for favorable news. It is all in the laps of the Gods. What puny things man’s efforts are in the face of the tremendous elements and the brutal facts of nature. I am very humble tonight.

By May 7, Algonquin’s fuel had run so low that it was forced to give up the search and prepare to return to Unalaska that evening. Wishaar continued to include in his letters news about the three other Army aircraft. Two days later, around 11:00 p.m. on May 9, Algonquin’s crew received word that Martin was safe. Per a May 12 letter:

About 11 pm May 9th we caught a radio [message] that Major Martin had suddenly appeared at Port Moller and was well. It was wonderful news. No doubt you know by now from the newspapers of his “resurrection” – of his flying in the snowstorm, crashing into the side of a mountain, burning his plane the first night for warmth, “mushing” through the snow and wind of that barren and unprotected country for days with little or no food, and finally, after seven days of cold and bitter hardship, finding an empty trapper’s cabin at the southern end of Port Moller Bay, where they recuperated for about 3 days and then mushed into the ”village” or cannery location of Port Moller.

One of the men at a local cannery could operate a small radio set, and it was from him that Wishaar was able to piece together the incredible story of Martin’s flight in heavy snow, eventful crash and ultimate survival. Wishaar’s May 12 letter continues:

The relief and actual joy in his final safety were reflected in the faces of everyone on board the Algonquin. After our rather first hard observations of his gallant and fearless efforts, the losing of his struggle and of his life was a terribly depressing thought. Having given him up for dead, in our thoughts, to have him found alive was electrifying. The expressions of everyone, after the news was known, was a study in real happiness, and the most passed-about idea was ‘won’t his wife be happy!’. It was a grand and glorious bit of news.

On the morning of May 10, eager to pick up Martin and Harvey, Algonquin left Unalaska for Port Moller. However, Martin had already arranged for a cannery tug to take them to Bellingham, Washington. Upon hearing this, Algonquin — at this point only some 80 miles from Port Moller — was ordered to return to Unalaska.

Martin and Seattle were officially out of the race to circumnavigate the globe after this harrowing incident. The remaining three planes successfully completed their flights and returned to Seattle on September 28, 1924. All the pilots, including Martin, received the Distinguished Service Medal. It was the first time this medal was awarded for acts not performed during war. Today, the wreckage of Seattle is on display at the Alaska Aviation Heritage Museum.

Aftermath

Wishaar dropped one “a” from his name in October 1926. In August of 1941, he was recalled to active duty as an aide to the captain of the Port of Boston. He retired for good in 1946 after serving a total of 24 years, six months, and ten days in the Coast Guard. He passed away on September 21, 1971 at the age of 84 in Florida and was interred at Arlington National Cemetery.