Richard Etheridge’s tenure in the U.S. Life Saving Service rightfully holds a prominent place in Coast Guard history. As the commanding officer (Keeper) of the all-Black Pea Island Life-Saving Station, he cataloged many achievements as a leader, surfman, and color-barrier breaker. In October of 1896, a shattered three masted schooner was blown off course. Two miles south of Pea Island, the E.S. Newman bottomed out on the shoals and launched a distress flare that was sighted on the stormy horizon by Keeper Etheridge’s crack surfmen. Keeper Etheridge ordered the crew into the ferocious surf rescuing nine souls. It would take 100 years to honor the Pea-Island surfmen with a Gold Lifesaving Medal.

Today, Keeper Etheridge is heralded into the community of Coast Guard greats for his professionalism and heroics in the U.S. Life Saving Service. Less explored are his deeds 32 years earlier when, as a Union soldier, he and thousands of other former slaves demonstrated the valor of the U.S. Colored Troops, proving themselves equal to any other fighting force on Earth.

Long before Etheridge’s days in the Army or the Life-Saving Service, he spent his youth an enslaved person in the household of John Etheridge. Born in 1842 on the Outer Banks of North Carolina to slave Rachel Dough, Richard’s paternal lineage remains an unresolved mystery. Richard’s enslaver (and possible father), John Etheridge, was a prominent local landowner and successful fishermen. John Etheridge’s nine slaves, including Richard, undoubtedly played roles in daily business operations and in the Etheridge family’s accumulation of wealth. Richard’s formative years aboard John’s fishing fleet of small boats was a school of instruction on the coastal, nautical, weathered way of life in the Outer Banks. This period would prove to be foundational for his later role as the Keeper of the Pea Island Life-Saving Service Station.

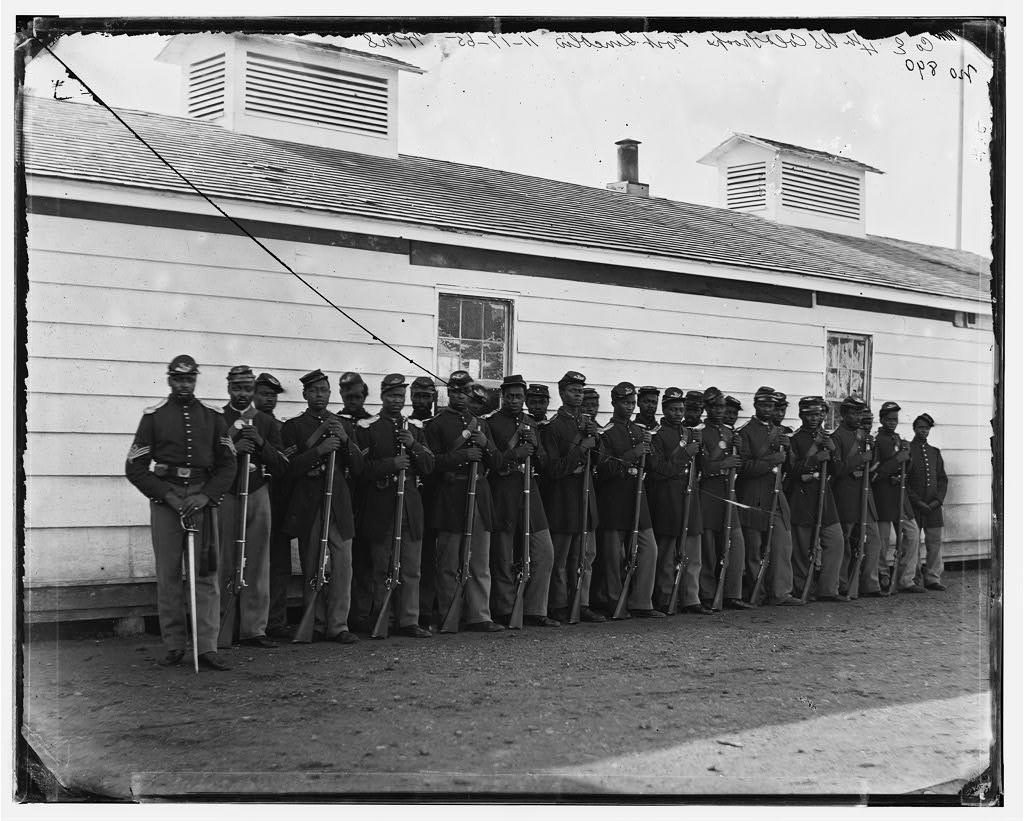

The Civil War came swiftly to the Outer Banks. In 1862, the region was occupied by the Union Army. By the summer of 1863, Union generals were recruiting hundreds of Black volunteers to form regiments of newly designated U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Richard leapt at the chance to fight for his people’s freedom and understood recruitment to be a mortal blow to the institution of slavery. Without permission or consultation from his former enslavers, Richard walked out and joined the Union Army on August 28, 1863. Sgt. Etheridge would learn valuable lessons from his commanding officer, Col. Alonzo Draper. A relentless disciplinarian and advocate for his men, the Colonel knew that only constant drill and high standards could prepare Sgt. Etheridge’s 36th USCT for battle.

The Civil War came swiftly to the Outer Banks. In 1862, the region was occupied by the Union Army. By the summer of 1863, Union generals were recruiting hundreds of Black volunteers to form regiments of newly designated U.S. Colored Troops (USCT). Richard leapt at the chance to fight for his people’s freedom and understood recruitment to be a mortal blow to the institution of slavery. Without permission or consultation from his former enslavers, Richard walked out and joined the Union Army on August 28, 1863. Sgt. Etheridge would learn valuable lessons from his commanding officer, Col. Alonzo Draper. A relentless disciplinarian and advocate for his men, the Colonel knew that only constant drill and high standards could prepare Sgt. Etheridge’s 36th USCT for battle.

By late fall of 1864, the situation on the ground had devolved into trench warfare. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had dug a series of fortifications and obstructions around Richmond and Petersburg, Va. Facing Lee, Union Gen. Ulysses Grant deployed along a 50-mile front his two armies, the Army of the Potomac, and the Army of the James.  A harbinger of the horrors of World War One, the landscape was a devastated snarl of abatis, chevaux-de-frise, earthworks, and artillery emplacements. Commanding the Army of the James, Gen. Benjamin Butler, had made several attempts to crack the Confederate lines at New Market Heights. Despite overwhelming superiority in manpower and materiel, the two attempts had little to show but 3,000 Union casualties. Undeterred generals Grant and Butler now looked to consolidate unused Union units in the area and prepare for another assault. Sgt. Etheridge’s 36th USCT was thus transferred to the Army of the James.

A harbinger of the horrors of World War One, the landscape was a devastated snarl of abatis, chevaux-de-frise, earthworks, and artillery emplacements. Commanding the Army of the James, Gen. Benjamin Butler, had made several attempts to crack the Confederate lines at New Market Heights. Despite overwhelming superiority in manpower and materiel, the two attempts had little to show but 3,000 Union casualties. Undeterred generals Grant and Butler now looked to consolidate unused Union units in the area and prepare for another assault. Sgt. Etheridge’s 36th USCT was thus transferred to the Army of the James.

Even this late in the war, Northerners still held the USCT in low regard. Caused by rampant Northern racism, disinclination to inflame rebel opponents, and distrust of untested African American regiments; commanders generally did their best to keep the USCTs from participating in major battles. Until September of 1864, the 36th USCT was relegated to guarding Confederate prisoners, laboring on Union construction projects, and making low-level raids against unorganized rebel insurgents and supply targets. This unspoken racial barrier of keeping Black units from major Union combat operations, led to a cycle of distrust. A cycle that could only be broken by military victory. General Butler spoke of this:

My white regiments were always nervous when standing in line flanked by colored troops, lest the colored regiments should give way and they [white soldiers] be flanked. This fear was a deep-seated one and spread far and wide, and the negro had had no sufficient opportunity to demonstrate his valor and his staying qualities as a soldier.

While the famed charge of the heroic 54th Massachusetts at Battery Wagner showed that Black units could fight and die with courage, there was yet to be a large strategic engagement displaying their ability to achieve a victory. In September of 1864, this opportunity was about to present itself to Sgt. Etheridge and the men of the 36th.

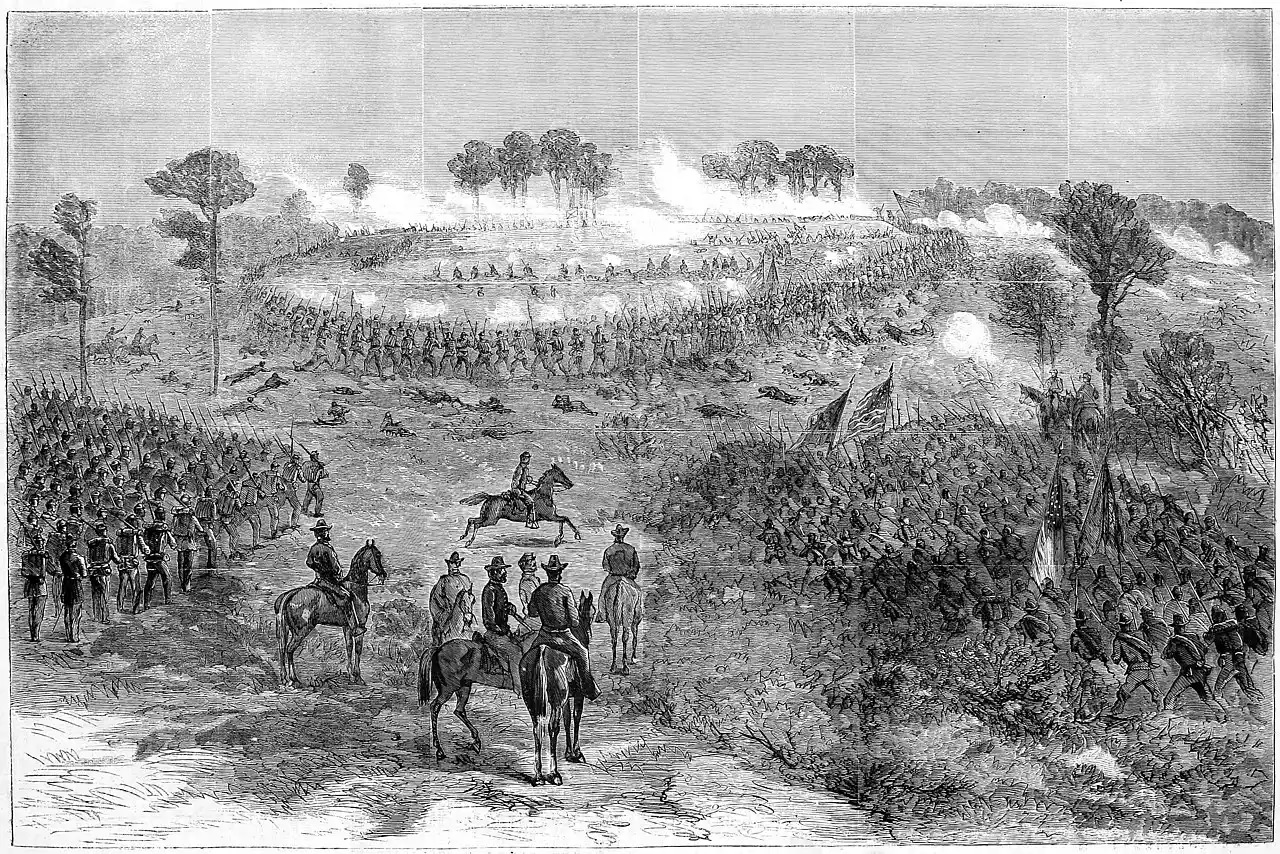

On the night of Sept. 28, Gen. Butler divulged his plans to his subordinates. A three-pronged attack would be ordered. Gen. Ord would hit Fort Harrison, simultaneously 3,800 troops under Brig. Gen. Charles Paine, along with the 36th would seize the New Market Heights, clearing the way for Brig. Gen. August Kautz cavalry to strike rebel positions to the north. Opposing the Bluecoats were around 1,800 battle-hardened veterans from the elite Texas Brigade. This unit represented the best troops the South had, with years of fighting experience in nearly every major campaign in the Army of Northern Virginia.

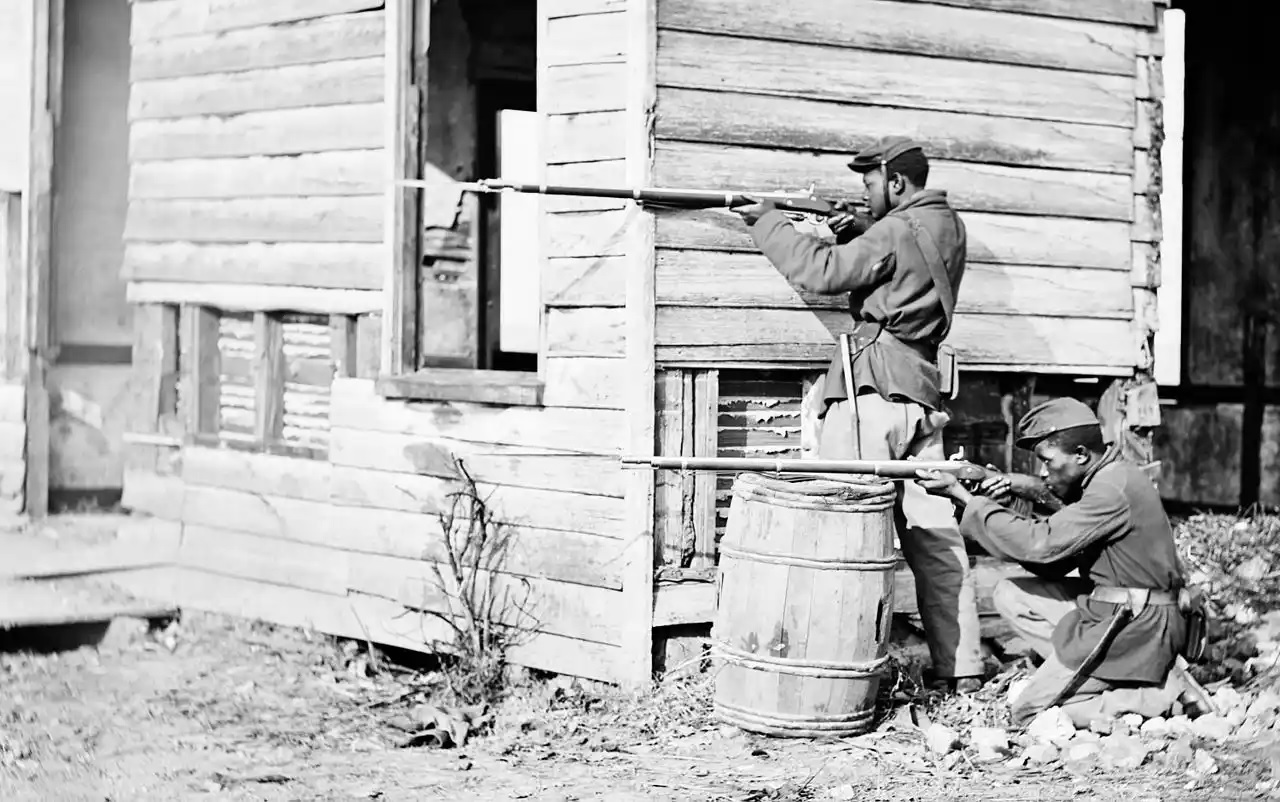

The 36th USCT, about 450 men strong, moved out to New Market Heights. The assault began with a blunder. The 4th and 6th USCT, 1,100 men under Col. Samuel Duncan, attacked the Confederate lines, unsupported by the rest of the task force. This piecemeal force approached the Southern lines and began hacking away at the abatis. As the Union men paused to clear the obstructions, the Texans let loose. The Southern barrage that followed wiped out ten men per minute. For nearly 40 minutes, the 4th and 6th held their lines until finally succumbing to retreat.

With the survivors of the 4th and 6th USCT streaming to the rear, new orders were issued. Attacking in piecemeal would not be done. The enemy could not be offered the luxury of engaging in a fire fight; Col. Draper ordered his brigade into a metaphorical hammer, rather than stretch his force along a lengthy battle line, the 5th, 36th, and 38th USCT would be arranged stacked one behind the other. The force would be ordered to charge the defending Texans with the bayonet, the 5th USCT would hurl themselves at the enemy, followed closely by successive hammering by the 36th and then 38th USCT. The goal was to split the enemy lines with a human cleaver. The successive attacks would overwhelm a single point in the Confederate lines, forcing the defenders into two frayed commands. Rifles were ordered not be fully loaded, if the Bluecoats were tempted to halt their charge and fire at the entrenched enemy, the Southern riflemen would shoot down the approaching Colored troops for sport. The only hope for carrying the earthworks depended on Sgt. Etheridge and his men charging the veteran Texans as one single unstoppable tide.

The command was given. Their fates decided, the works were to be charged with fixed bayonets and Sgt. Etheridge stepped off, shoulder to shoulder with his comrades of the 36th. As the three regiments closed through a forest of small pines the sun began to burn off the fog layer that had obscured the battlefield all morning. Continuing their march, Sgt. Etheridge now observed the horror left from Duncan’s initial assault. Blue-clad heaps lay in varying states of death, and destruction cluttered the approach. The Texans had made short work of the USCTs. Nearly 400 men from the 4th and 6th, almost nearly 60 percent of their initial strength, had been cut down before the Confederate lines of New Market Heights. Sgt. Etheridge and the 36th surged forward through the swampy terrain. Stepping over their shattered comrades, they began to take artillery fire. As exploding shell fragments raked the Union battlelines, the men of the 36th struggled to maintain formation as they slogged through Four Mile Creek.

Col. Draper’s Brigade began to fall into a state of confusion. This was the moment the enemy had been waiting for. Confederate riflemen let loose a ferocious volley of lead, cutting gaps into the blue battle line. Forgetting their mandate to carry the fortifications by point of bayonet, the attackers bogged down. Soldiers dove for cover and fired back toward the enemy. Well situated behind their defenses the Confederates felt little effect from the Union volleys. Thirty minutes of deadly confusion reigned. Col. Draper, his officers, and non-commissioned officers like Sgt. Etheridge, cursed, shouted, ordered, and cried, extorting their men to reform and charge the earthworks. Slowly but surely, the men of the 36th clawed back their momentum. With the formidable Yankee battleline reforming and clambering over a second line of abatis, the outnumbered Confederate defenders began disengaging. The Southerners fled the field, some in orderly retreat and others in full panic.

Col. Draper’s Brigade began to fall into a state of confusion. This was the moment the enemy had been waiting for. Confederate riflemen let loose a ferocious volley of lead, cutting gaps into the blue battle line. Forgetting their mandate to carry the fortifications by point of bayonet, the attackers bogged down. Soldiers dove for cover and fired back toward the enemy. Well situated behind their defenses the Confederates felt little effect from the Union volleys. Thirty minutes of deadly confusion reigned. Col. Draper, his officers, and non-commissioned officers like Sgt. Etheridge, cursed, shouted, ordered, and cried, extorting their men to reform and charge the earthworks. Slowly but surely, the men of the 36th clawed back their momentum. With the formidable Yankee battleline reforming and clambering over a second line of abatis, the outnumbered Confederate defenders began disengaging. The Southerners fled the field, some in orderly retreat and others in full panic.

The ground was seized, the defenders were in full retreat to Fort Harrison, and Confederate Forces had decisively lost ground that would never be retaken. Beyond the tactical gains lay an even more remarkable accomplishment; former slaves like Sgt. Etheridge had fought for their freedom as soldiers. In a world full of racism and doubt, these men shattered the false narrative of inferiority. Instead, the U.S. Colored Troops had proved themselves to be heroes to their country, and victors beyond reproach, earning 14 Medals of Honor.

After the battle, journalists like Thomas Cook from the New York Herald would report:

The colored troops of General Paine’s division ... were directed to carry this position. Their charge ... was made with a vigor and determination that would have done credit to the best organizations of white troops in our armies. They never halted or faltered though their ranks were sadly thinned by the charge, and the slashing was filled with the ... (dead) and wounded of their number. The successful accomplishment of their task put the enemy to confusion and sent them in a rapid retreat up the round towards Richmond.

The price of this victory was high. Though Sgt. Etheridge remained unscathed, nearly a quarter of the men in the 36th USCT were killed or wounded. Etheridge’s unit served through the war’s end in April 1865. Soon after the fall of the Confederacy, the 36th was shipped to Texas to enforce the final emancipation of slaves on June 19th, a day now known as Juneteenth.

Sgt. Etheridge returned home a free man, a veteran, and resolved to live the “American Dream.” He met and married his wife, returned to fishing, and bought over 100 acres of land. With the expansion of the U.S. Life-Saving Service under General Superintendent Sumner Kimball came the establishment of a series of lifesaving stations along the deadly Carolina coast. Choosing again a life of service and selflessness, Richard Etheridge donned the uniform of his new service. As we approach the Juneteenth observance, we recognize the contributions future Coast Guardsmen will make for the cause of freedom.