Now I know where seabirds go during hurricanes.

On October 21, 1969, The 67-foot wooden fishing vessel Dell G, a former codfish schooner with cut-down masts, just survived a “squall line” reported when asking for assistance from the Coast Guard in New Orleans at 1:10 p.m. A cable coiled on deck slipped overboard, fouling its propeller. One of the seven crewmembers radioed, reporting they were also attempting to halt flooding through a forward hatch.

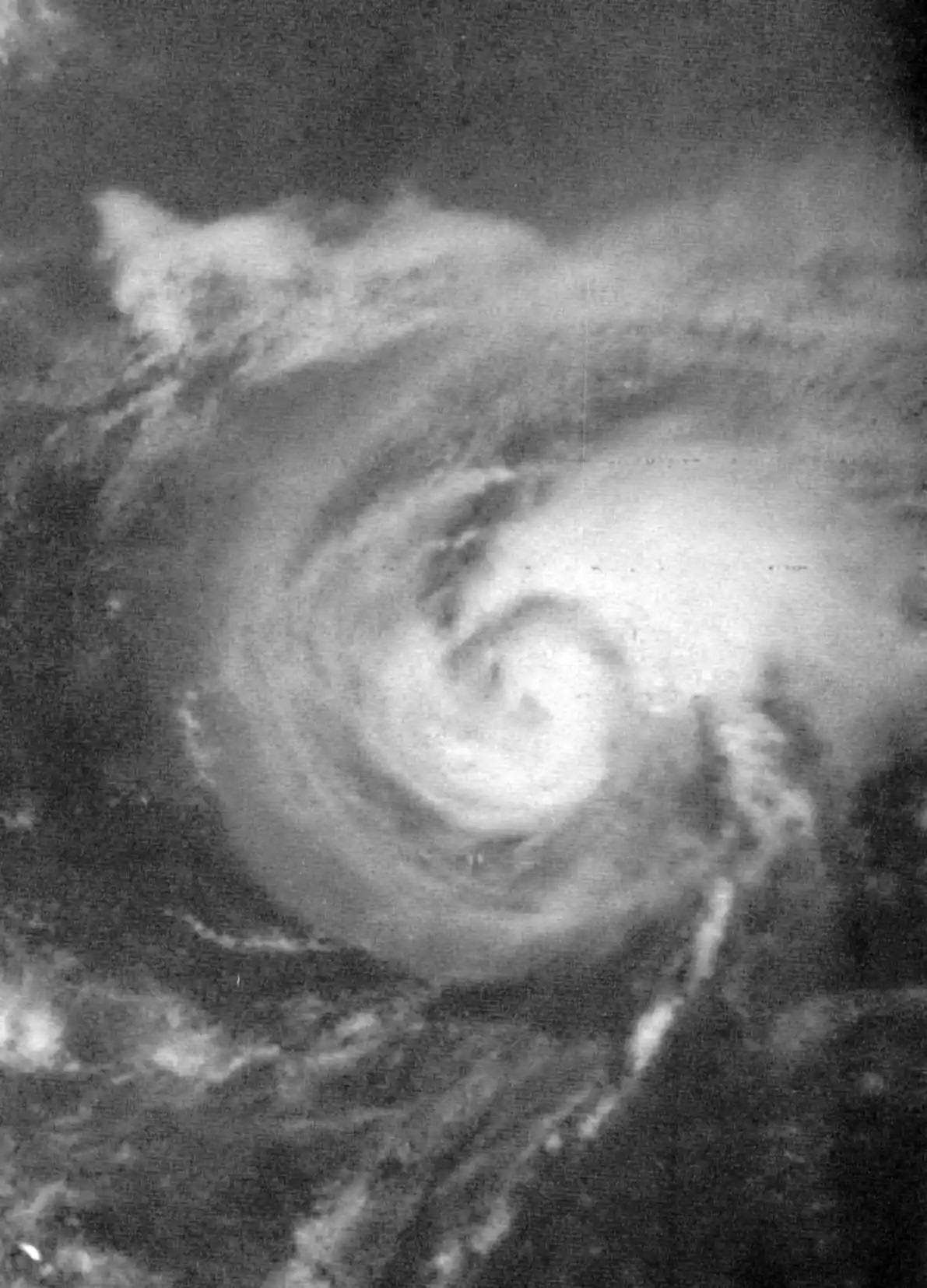

About an hour later, I was called to the operations center at Coast Guard Aviation Training Center (ATC), Mobile, Alabama, as the duty SAR fixed-winged pilot. Rescue Coordination Center New Orleans reporting, “Fishing boat in trouble about 200 miles south of the Mississippi River outlet. Also, a hurricane there.” I glanced at the weather plot, noting that the boat’s position was near the center of Hurricane Laurie. This may be a reason the fishing vessel was reporting clearing skies. A five-minute flight plan followed with a scheme to penetrate the eye of the hurricane.

I planned to fly from Mobile to the boat’s position about 300 miles away. My flight plan would take me downwind on the storm’s western edge, boosted along with tailwinds, then arcing into the eye from the seven o’clock position — looking at the eye from above, like a clock with north being twelve o’clock. We should expect minimum storm effects at this location — or so l learned in “meteorology” classes in flight training a decade and a half earlier. “Should.”

My co-pilot was Lt. Bill Barker, who got his check flight in the fixed-wing amphibian HU-16E “Albatross” a week earlier at ATC Mobile’s HU-16E qualification and transition school — from me! Lt. j.g. Donnie Polk — just out of flight training, stood nearby as a casual observer in the op center. I instantly appointed him as navigator. I doubted he had ever seen a Loran-A set before. Usually, we did not carry a third pilot/navigator on typical SAR flights. This flight might be different.

Next, I called for an extra dewatering pump added to the one typically carried on board the aircraft and an additional 20-person life raft.

The Grumman Albatross, Coast Guard number 2125, took off Bates Field in Mobile at 2:50 p.m. In addition to the three pilots in our crew, were ATC Weems Adams, ASM1 Donald Cosgrove, AD2 Henry Beasley, and AT3 Carl Lane.

The Grumman Albatross, Coast Guard number 2125, took off Bates Field in Mobile at 2:50 p.m. In addition to the three pilots in our crew, were ATC Weems Adams, ASM1 Donald Cosgrove, AD2 Henry Beasley, and AT3 Carl Lane.

The trip through this storm was rapid and eye-opening. An average of 50-knot hurricane tailwinds boosted our normal cruising airspeed of 165 knots to well over 200 knots ground speed. We made quick time arcing along the western edge of the storm flying at 500 feet, keeping visual contact with the water. Most of the broken clouds were above this level. Sometimes, to keep water in view, we dipped down as low as 200 feet. This altitude gave us visibility of sea-surface conditions to judge winds.

As we closed on the storm’s 9 o’clock position, or abeam the storm’s eye on the western side, the seas driven by 40-knot winds, built up to 10 to 20 feet with tops blown off in long streaks. Soon, winds over 50 knots blew tops off swells. At over 60 knots, the sea surface was flat, viewed from above with no definition other than a slick surface of blowing water. I started my left turn into the storm’s eye by heading more southeasterly around the 8 o’clock position. Very soon after, when I believed we were near the weakest area of the hurricane’s eye, I turned the Albatross to the northeast. This was only a guess based on theory, old classroom instructions, and intuition. We didn’t have modern satellite data back then.

Winds now were in the seventies and increasing. Cloud cover was complete with severely reduced visibility in solid rain. Blowing spume defined the flat seas. Reported wind velocity was 90 knots, steady, with higher gusts. The sea and sky were indivisible. Rain and blowing seas merged into one white matrix.

On instruments now. Down to 200 feet and still trying to keep in view of the surface. Impossible. Bill called out the altitude from the radar altimeter. The pressure altimeter readings climbed rapidly with plane descending approaching the storm’s eye low pressure. The view through the windshield was white with solid rain! Solid water.

The stiff, unflexing wings of the Albatross transmitted turbulence through the hull, bouncing the plane and crew. Harnesses could not be too tight on this rodeo ride.

Instantly, sunlight! No wind. Clear skies. The sea surface was flat and oily looking but undulating with huge pop-up waves. We were in! And this is where we found thousands of seabirds soaring along with us in the storm’s eye.

For the next two hours, we circled in a three- to five-mile-wide clearing and dodged birds. The disabled fishing vessel Dell G basked in sun beaming down through a deep, hollow well in the center of the tempest. We saw the rolls of cables on deck and the single cable creating their problem draping over the boat’s side and trailing down into the water’s clear depths.

Once we made radio contact with Dell G, we relieved NOAA’s aircraft, ESSA 39, of its communications relay duties. No ships were in the area to provide on-site services to Dell G. The service’s Rescue Coordination Center dispatched Coast Guard cutter Dependable with a next day estimated time of arrival, and diverted the commercial vessel, SS Atlantic Heritage, to the scene. At 9:15 a.m. the following morning, the Atlantic Heritage would arrive alongside Dell G.

Our relief efforts were meager. We had two dewatering pumps we could deliver by dropping with parachutes and two life rafts, also delivered by dropping. The Dell G’s need for either was not critical. The fishing vessel’s crew had flooding controlled, but they still had no way to clear the propeller for maneuvering. We proceeded with a just-in-case effort by attempting to deliver the first dewatering pump. We flew the drop pattern at 200 feet using the seaman’s eye to determine the exact moment for the drop by calling out for the crew aft and depending on them to respond exactly at the moment they received the command, “drop, drop, drop.”

The intent was to get as close to the boat without hitting it. A light 200-foot poly rope trailed the package with our attempt to drape the rope across the vessel. The first drop was very close — close enough in most situations, but the rope did not cross the boat. Also, when the dewatering pump package hit the water, a wave the size of a huge barn, surged upwards. The boat slid down one side, and the pump slid down the other side separating boat and pump by a few hundred feet. The sea surface in the storm’s eye was a constant upwelling of mounding waves with no direction or pattern. Bill and I took turns dropping. This same delivery success followed with the next three packages, which included the rafts. Close, but in each instance, boat and package separated by the unpredictable upwelling waves. The boat had no propulsion and could not maneuver to reach the packages. With these life-saving devices drifting away, we could only monitor the Dell G by flying tight circles within the eye wall over the next two hours — dodging birds!

I didn’t have the heart to tell Dell G’s crew that the “squall line” they reported earlier having passed over was not the last. We calculated with the storm moving east-northeast at about six knots, that the other edge of the hurricane’s eye was going to hit them just after dark.

Darkness fell suddenly in the eye with the storm’s western wall shading the setting sun — time to leave. We could provide no further assistance. Dell G’s calm was ending, as was ours.

Now came the most terrifying part of the day — flying back into the storm’s eyewall. It looked like a solid granite cliff but moving sideways at 90 knots. We slowed airspeed to absorb the turbulence as we approached at 500 feet and 135 knots. The view of the sea surface was weird. Where we were in the eye, the surface was slick with no wind. At the very edge of the eyewall, the sea’s surface blended, sucked up, and mixed with the sideways blowing rain along a sharply defined wall of water. For the past two hours, we had flown in calm, smooth air. Later on, I imagined seeing the plane’s nose suddenly thrust sideways at 80 knots while the tail continued ahead, not yet to the wall, in the calm air at 135 knots. The moment the plane’s nose punched into that wall; our harnesses were not tight enough to keep us in our seats.

And, at this moment, the right engine’s chip detector light illuminated. On solid instruments at 500 feet in flooding rain, wind, and extreme turbulence, we had a problem. Engine gauges revealed no issues. However, as a precaution, we decided not to demand more power than we were using — a slow cruise power setting.

This situation created an additional problem — Mobile was located 300-miles upwind. Now fighting the circulating hurricane wind not in our favor, our ground speed was only in double digits — making the return home more than three hours. Not enough fuel remained to get back. Furthermore, we had this worrisome engine. New Orleans, now, was our only refuge — if we could even make it there.

We landed at Naval Air Station New Orleans two hours later. A quick check by our mechanics determined this engine was not going to power this airplane again. The crew discovered damage beyond repairs. We got a ride home in a helicopter flown from Mobile to receive us.

And in walking around the Albatross, inspecting it after landing, I did not find a single bird strike.

[Editor’s note: The 67-foot fishing vessel Dell G managed to survive Hurricane Laurie and was later towed to safety by a Coast Guard cutter. Cmdr. Tom Beard retired from the service after a 20-year career as a Coast Guard aviator. Like many of the fleet of Coast Guard Albatross aircraft, Number 2125 flew its last mission to “The Boneyard” of surplus military aircraft located at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, Arizona. The 2125 became a spare parts airframe before being scrapped.]