When Navy officials asked World War II Commandant Russell Waesche to choose a Coast Guardsman whose name should grace a new Fletcher-class destroyer, he singled out Revenue Cutterman Frank Hamilton Newcomb as by far the best candidate.

When Navy officials asked World War II Commandant Russell Waesche to choose a Coast Guardsman whose name should grace a new Fletcher-class destroyer, he singled out Revenue Cutterman Frank Hamilton Newcomb as by far the best candidate.

A man of modesty, humility, and strong work ethic, Frank Newcomb was born in 1846 and raised in Boston. As a teenager, he sailed on his father’s merchant ship and, at age 17, he began serving in the Union Navy’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. After the Civil War, Newcomb received a third lieutenant’s commission and served the 1870s and 1880s on Revenue Cutters and as an inspector for the United States Lifesaving Service, helping to establish the first all-black station located at Pea Island, North Carolina.

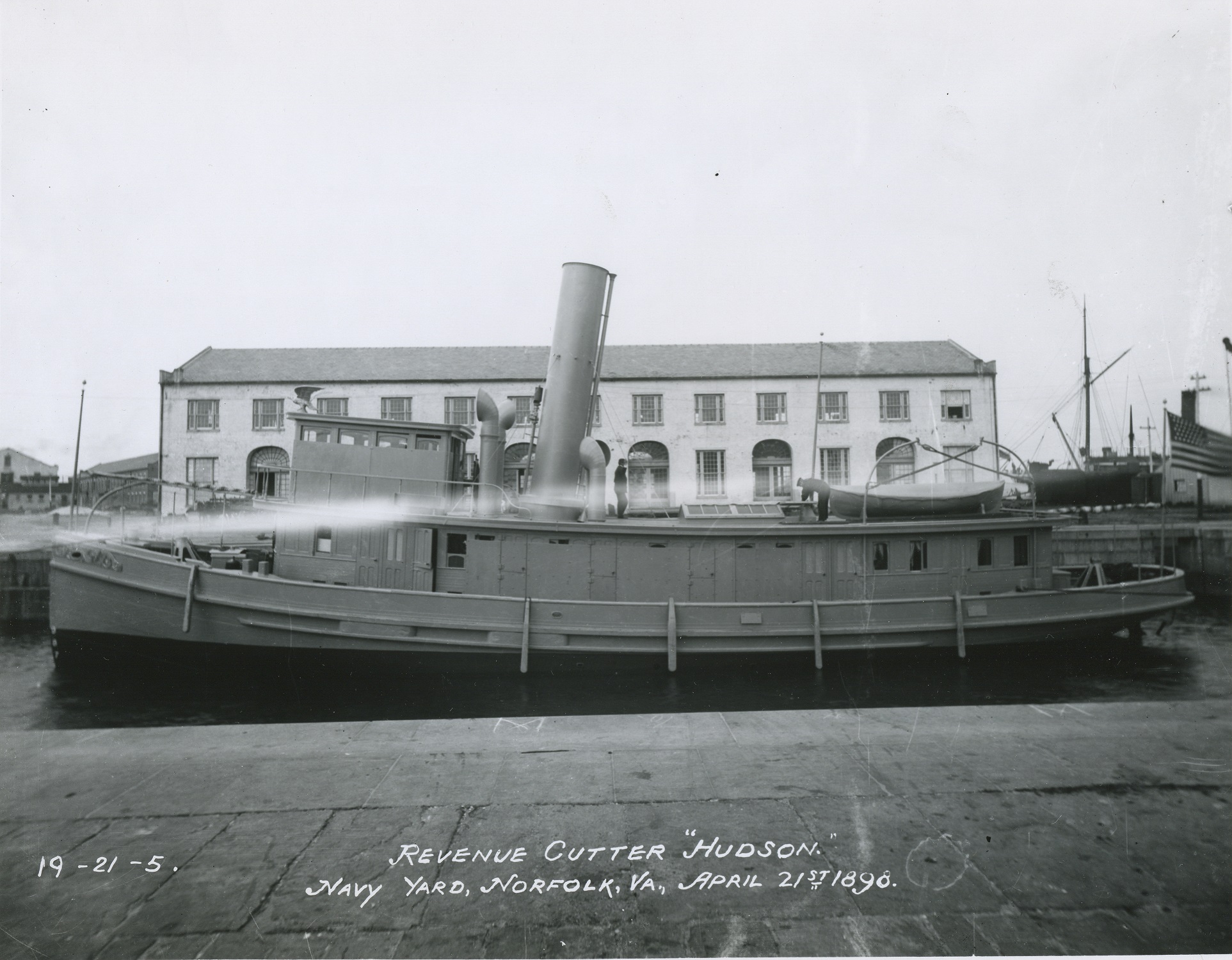

During the 1890s, tensions mounted between the United States and Spain over the island of Cuba. At the time, Newcomb served on cutters in Pacific waters. But in September 1897, he assumed command of the Revenue Cutter Hudson, home-ported in New York Harbor. The tensions between the U.S. and Spain simmered until they boiled over in February 1898, with the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbor. On the second day of April, Hudson slipped her moorings and steamed south to the Norfolk Naval Shipyard to prepare for war.

The Norfolk Navy Yard was buzzing with activity when Hudson arrived to take on arms, armor, and ammunition. The service’s first steel-hulled cutter, the ninety-four-foot Hudson had a tugboat design; and her crew included five officers and eighteen enlisted men, including two warrant officers, a cook, ship’s steward, and ship’s boy. Hudson later received two six-pound rapid-firing guns, one each located fore and aft; and a Colt automatic “machine gun” mounted on top of the deckhouse. It also had a layer of five-eights-inch armor bolted around the pilothouse and deckhouse.

On April 21st, Congress declared war with Spain and the Treasury Department transferred several revenue cutters, including Hudson, to the Navy. Newcomb found himself serving as a part of the U.S. Navy once again. Within two days, Hudson set out from Norfolk f or Key West, Florida, the staging area for U.S. Naval operations around Cuba. Off the Outer Banks of North Carolina, the cutter met with a severe storm, including hurricane winds, thunder, lightning, mountainous seas, torrential rain and hail the size of “hen’s eggs.” The storm nearly washed away Hudson’s pilothouse, but the new armor plate held everything together against the heavy seas. On Thursday, May 5th, Hudson finally arrived in Key West and Newcomb received his orders.

or Key West, Florida, the staging area for U.S. Naval operations around Cuba. Off the Outer Banks of North Carolina, the cutter met with a severe storm, including hurricane winds, thunder, lightning, mountainous seas, torrential rain and hail the size of “hen’s eggs.” The storm nearly washed away Hudson’s pilothouse, but the new armor plate held everything together against the heavy seas. On Thursday, May 5th, Hudson finally arrived in Key West and Newcomb received his orders.

Due to its relatively shallow draft of 10 feet, the Naval command assigned Hudson to blockade the Cuban coast between the ports of Cardenas and Matanzas. On May 9th, the cutter took up its duty station and by the 10th, Newcomb began scouting the approaches to Cardenas Bay. Cardenas had three Spanish gunboats defending it, and Newcomb tried his best to draw the vessels out for a fight, but they refused to leave the safety of the bay. Newcomb then sounded the two main channels into the bay only to find them filled with debris. He considered plowing his way through the debris but feared the presence of underwater mines. After further reconnaissance, he found a third channel with no debris that was passable only by shallow-draft vessels at high tide.

Newcomb developed a plan to capture the gunboats by sending American warships through the third channel. On Wednesday, May 11th, gunboats USS Machias and USS Wilmington, and torpedo boat USS Winslow appeared outside Cardenas Bay to assist with Newcomb’s plan. The Machias drew too much water to enter the bay and participate in the attack on Cardenas. Instead, it laid down a barrage on the barrier islands to eliminate enemy snipers from the bay’s entrance. During high tide, between noon and 1:00 p.m., Hudson, Wilmington, and Winslow steamed slowly through the narrow passage. Wilmington’s captain, Cmdr. Coleman Todd, sent Hudson in search of the gunboats on the eastern side of the bay and ordered Winslow to search the western side. Later, Winslow and Wilmington rendezvoused 3,500 yards off Cardenas, where Commander Todd spied the enemy gunboats moored at the city’s waterfront.

Todd directed Winslow’s commanding officer, Lt. John Baptiste Bernadou, to investigate the situation. A Foote-class torpedo boat, Winslow seemed perfectly suited to capture or destroy the Spanish gunboats. It carried one-pound rapid-fire guns and torpedoes and drew only five feet. Winslow also carried a crew of 20 enlisted men and two officers. Executive officer Ensign Worth Bagley, came from a distinguished North Carolina military family that included brother-in-law Josephus Daniels, future Secretary of the Navy.

As often happens in combat, the original plan of attack fell apart after the fighting began. Bernadou backed the stern of Winslow toward Cardenas, likely to minimize exposure to the enemy, make use of the stern-mounted torpedo and allow for a fast exit strategy. But as soon as Winslow came within 1,500 yards of the city’s wharves, Bernadou found himself sitting between white range buoys deployed by Spanish artillerymen to aim their guns. The enemy gunners opened fire with one-pound guns from the moored gunboats and salvoes fired from heavier artillery hidden along Cardenas’s waterfront.

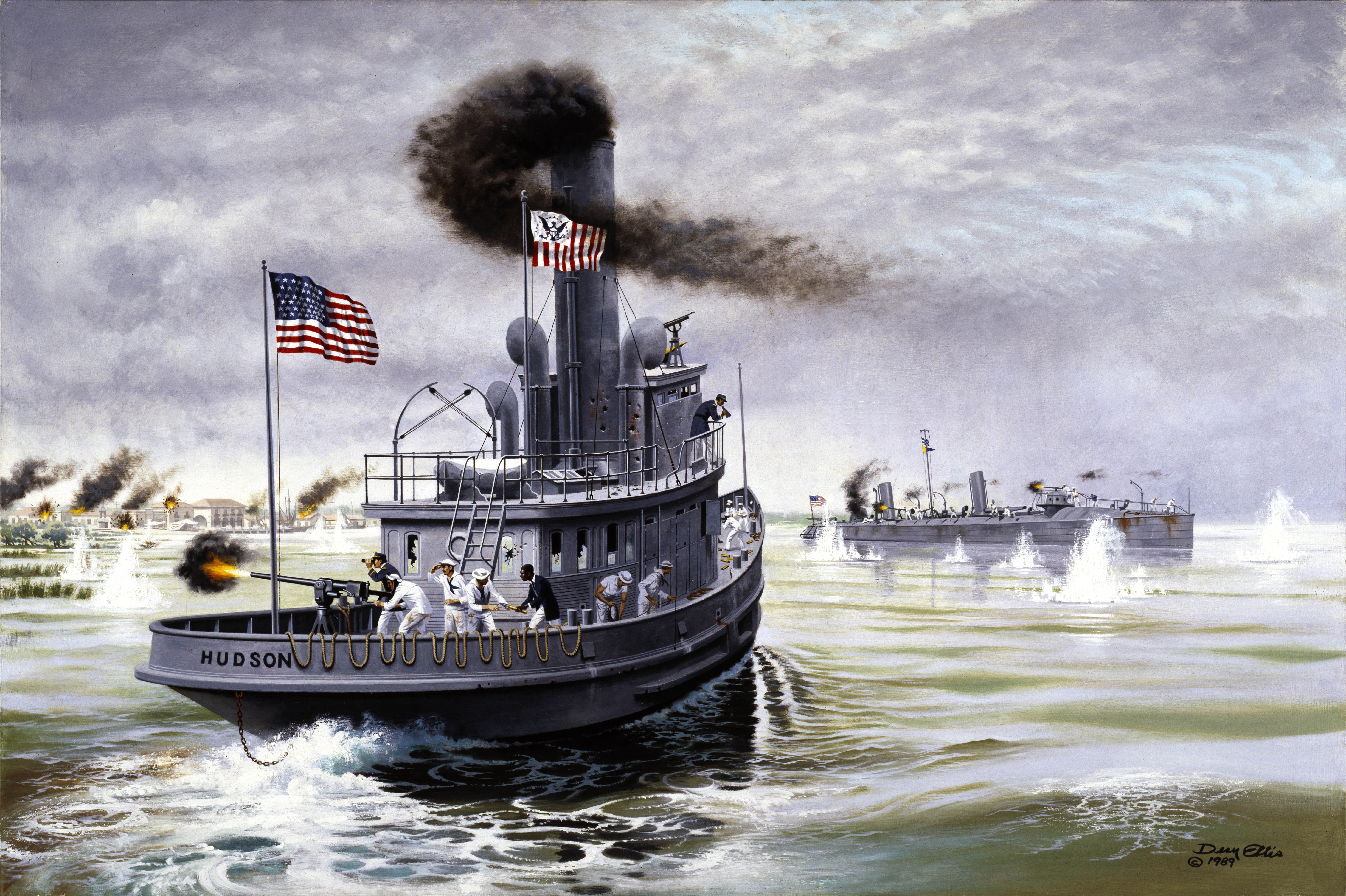

After witnessing the initial salvoes, Hudson steamed at top speed from the bay’s eastern side and Newcomb requested permission from Commander Todd to engage the enemy. By 2:00 p.m., the Spanish gunboats and artillery had fired on the Winslow, Hudson, and the distant Wilmington, with its heavier four-inch guns. According to an eyewitness account, Spanish guns rained down shells from half-a-dozen direc

After witnessing the initial salvoes, Hudson steamed at top speed from the bay’s eastern side and Newcomb requested permission from Commander Todd to engage the enemy. By 2:00 p.m., the Spanish gunboats and artillery had fired on the Winslow, Hudson, and the distant Wilmington, with its heavier four-inch guns. According to an eyewitness account, Spanish guns rained down shells from half-a-dozen direc tions, but the enemy positions were tough to spot because the Spanish used smokeless powder ammunition. The Americans relied on outdated black powder, which clouded the gun crews’ vision and alerted the enemy of incoming shells.

tions, but the enemy positions were tough to spot because the Spanish used smokeless powder ammunition. The Americans relied on outdated black powder, which clouded the gun crews’ vision and alerted the enemy of incoming shells.

As the battle raged, Spanish gunners focused their fire on Winslow, shooting down its smokestack and ventilator, holing its armored conning tower, and disabling the steering gear and engines. In addition, an onshore wind was pushing the crippled vessel toward shore and shallow water. Bernadou called out to the approaching Hudson, “I am injured; haul me out.” Newcomb reacted instantly, steering Hudson through the muddy shallows and churning up brown water with her propeller. The cutter came in close while Bagley and several of Winslow’s crew stood on deck to receive a heaving line from the Hudson. The enemy fire intensified, and Bagley yelled out, “Heave her. Let her come. It’s getting pretty hot here.” By the time Hudson closed the distance, an enemy shell exploded on Winslow, killing Bagley and an enlisted man and mortally wounding three crewmembers. These men were the first casualties of the Spanish-American War and Bagley the first American officer killed in the conflict; several posthumously received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Despite the enemy shelling, unfavorable winds and shallow water, Hudson’s crew managed to secure a three-inch hawser to the Winslow and began towing it out of range. Within minutes, the hawser snapped due either to the strain or an incoming shell. Newcomb persevered, exclaiming “We will make it fast this time.” Risking his own vessel and crew a second time, Newcomb plowed further into the mud, backing and filling to carve a ditch in the sea floor to the stricken Winslow. Hudson’s engineers never missed an engine order bell during the cutter’s fast-changing steam engine operations. Meanwhile, the cutter’s deck crew secured a line to Winslow and made fast the torpedo boat beside the cutter in tugboat fashion. This time, Newcomb succeeded in hauling the stricken vessel beyond the range of enemy guns.

Hudson not only saved the Winslow from certain destruction, but it also poured 135 six-pound shells into the enemy in 20 minutes. After the fierce firefight, Newcomb received orders to ferry Winslow’s dead and wounded to medical facilities at Key West. In the evening, the casualties were loaded aboard the cutter and Newco mb steamed at top speed to the Navy’s base of operations, arriving at 7:00 a.m., the next day. In one exhausting 24-hour period, Newcomb and his men had scouted Cardenas Bay, fought the enemy, rescued Winslow, and sped casualties to distant Key West.

mb steamed at top speed to the Navy’s base of operations, arriving at 7:00 a.m., the next day. In one exhausting 24-hour period, Newcomb and his men had scouted Cardenas Bay, fought the enemy, rescued Winslow, and sped casualties to distant Key West.

In mid-August, at the conclusion of the brief war, the cutter returned to a rousing welcome at its homeport of New York. In a special message to Congress, President William McKinley congratulated Hudson for rescuing the Winslow “in the face of a most galling fire” and recommended special recognition for the crew. A joint resolution of Congress provided the cutter’s line and engineering o fficers with Congressional Silver Medals and Bronze Medals to her enlisted crewmembers.

fficers with Congressional Silver Medals and Bronze Medals to her enlisted crewmembers.

Lt. Frank Newcomb’s courage and determination had prevailed against heavy odds in the daredevil rescue of USS Winslow. He received the war’s only Congressional Gold Medal, also known as the Cardenas Medal. In addition, the Revenue Cutter Service advanced Newcomb seven points in the promotion system, fast-tracking him to the senior rank of captain in 1902. Despite this recognition, many familiar with the Battle of Cardenas Bay strongly believe Newcomb deserved the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism and stubborn determination in the face of fierce enemy fire.

Frank Hamilton Newcomb retired in 1910 after 40 years of service and received the flag rank of commodore in retirement. Newcomb died in 1934 and his body was laid to rest on Coast Guard Hill beside other service heroes at Arlington National Cemetery. From his birth in Boston to the naming of a hard-fighting World War II destroyer in his honor, the story of Frank Hamilton Newcomb spanned a century. Newcomb was a member of the long blue line, and his career proved a testament to the U.S. Coast Guard’s core values of honor, respect, and devotion to duty.