Manhattan Beach—Building a World War II Training Center

Manhattan Beach—Building a World War II Training Center

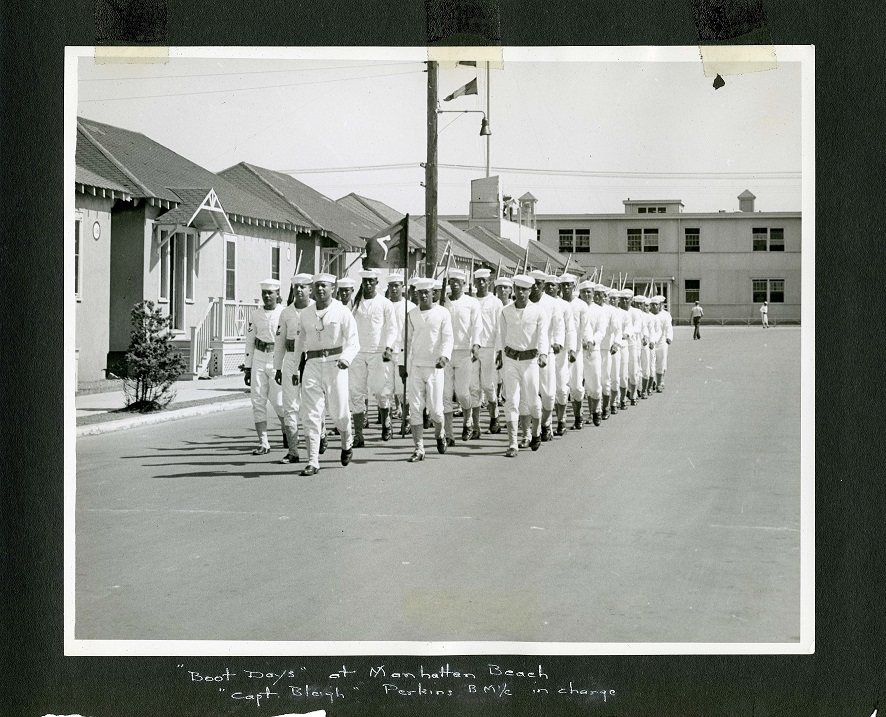

It was World War II and most able men wanted to serve their country and United States Coast Guard welcomed many of these young volunteers. For African Americans, their service would begin at Manhattan Beach Training Center in Brooklyn, New York. Here, black “Coasties” would receive their initial indoctrination and training, or “boot camp.”

When President Franklin Roosevelt made it clear that blacks were to be enlisted, Coast Guard Commandant Russell Waesche already had a plan. The Coast Guard would enlist approximately  500 African Americans in the general service for all enlisted ratings. Some 300 of these men would be trained for duty on small vessels, the rest for shore duty under the Captain-of-the-Port of six U.S. seaports. Although Waesche’s plan made no provision for training black petty officers, 50 to 65 percent of the crew in small cutters and miscellaneous craft usually held such ratings, and it followed that blacks would eventually be allowed to “strike” for such ratings.

500 African Americans in the general service for all enlisted ratings. Some 300 of these men would be trained for duty on small vessels, the rest for shore duty under the Captain-of-the-Port of six U.S. seaports. Although Waesche’s plan made no provision for training black petty officers, 50 to 65 percent of the crew in small cutters and miscellaneous craft usually held such ratings, and it followed that blacks would eventually be allowed to “strike” for such ratings.

Manhattan Beach is located in an area bordered by Jamaica Bay to the south and east, and Sheepshead Bay to the north. By the early 1920s, it had become a summer vacation spot for New Yorkers. In 1942, the Coast Guard acquired the eastern end of the Manhattan Beach peninsula and began building a training center. Marshlands were filled, some of the existing structures were left standing and had their partitions changed or removed for military use. Some structures were removed altogether and new barracks were built with double deck bunks, rifle racks, toilets and sinks. Among the newer facilities, training buildings large enough to house groups of 30 or more recruits were built with a shower room of about 50 sinks and 100 showerheads.

Recruits and Trainers

In the spring of 1942, the Coast Guard recruited its first group of 150 black volunteers, sending them to Manhattan Beach for basic training. The lack of African American general service trainees prevented the construction of a separate training station, so blacks were formed into a separate training company at Manhattan Beach. While training classes and daily duty activities were integrated, sleeping and messing facilities were still segregated. During World War II, African Americans in the Navy and Marine Corps were trained in separate training camps from white recruits.

Many African American “boots” from the East Coast were inducted at the local Coast Guard headquarters in Baltimore. From there, they travelled by rail to New York City and by bus to Manhattan Beach in Brooklyn. The process of induction and travel to Manhattan Beach Training Center was different for everyone.

On base, recruits received training in seamanship, knot-tying, basic firefighting, deck maintenance, and line throwing. Seamanship skills were also honed aboard a full-scale ship replica, named “Coast Guard Cutter Neversail.” Built on land, this “ship” provided recruits a sense of life, conditions, space, and duties in different parts of a vessel underway. Other parts of the post had built-in “abandon ship” stations where the recruits learned, among other things, to muster at assigned stations and how to board and launch survival craft.

On base, recruits received training in seamanship, knot-tying, basic firefighting, deck maintenance, and line throwing. Seamanship skills were also honed aboard a full-scale ship replica, named “Coast Guard Cutter Neversail.” Built on land, this “ship” provided recruits a sense of life, conditions, space, and duties in different parts of a vessel underway. Other parts of the post had built-in “abandon ship” stations where the recruits learned, among other things, to muster at assigned stations and how to board and launch survival craft.

Seaman First Class Robert Thompson initially volunteered to join the U.S. Navy. Turned down because he was “too skinny” he volunteered at the Coast G uard recruiting station in Washington, D.C. He was inducted at the Coast Guard center in Baltimore and, with six other volunteers, traveled to Manhattan Beach. He and the other recruits arrived at the training center at 4:00 a.m. Weary and tired from the trip, he and his companions laid down to rest, only to be awakened two hours later by shouts of “Hit the deck!” Thompson had not heard the expression before, but it would become very familiar over the next four weeks.

uard recruiting station in Washington, D.C. He was inducted at the Coast Guard center in Baltimore and, with six other volunteers, traveled to Manhattan Beach. He and the other recruits arrived at the training center at 4:00 a.m. Weary and tired from the trip, he and his companions laid down to rest, only to be awakened two hours later by shouts of “Hit the deck!” Thompson had not heard the expression before, but it would become very familiar over the next four weeks.

Once they arrived, recruits received a physical examination, vaccinations, uniforms, and an introduction to Coast Guard traditions and discipline. Breakfast came after morning exercise and “dressing your bunk.” Thompson recalled that, “breakfast and the rest of the chow was always great.”

Retired Master Chief Boatswain’s Mate Robert Hammond volunteered in Harlem, New York. After enlisting, he was sent home to await orders. He later learned there were not enough African American volunteers to start a new company of recruits. A few days later, he received the call to muster and travel by bus to nearby Manhattan Beach. He recalled, once he arrived, the uniform of the day was announced about five minutes before muster for breakfast at 5:30 a.m. Uniform of the day usually included leggings, polished boots and square hats.

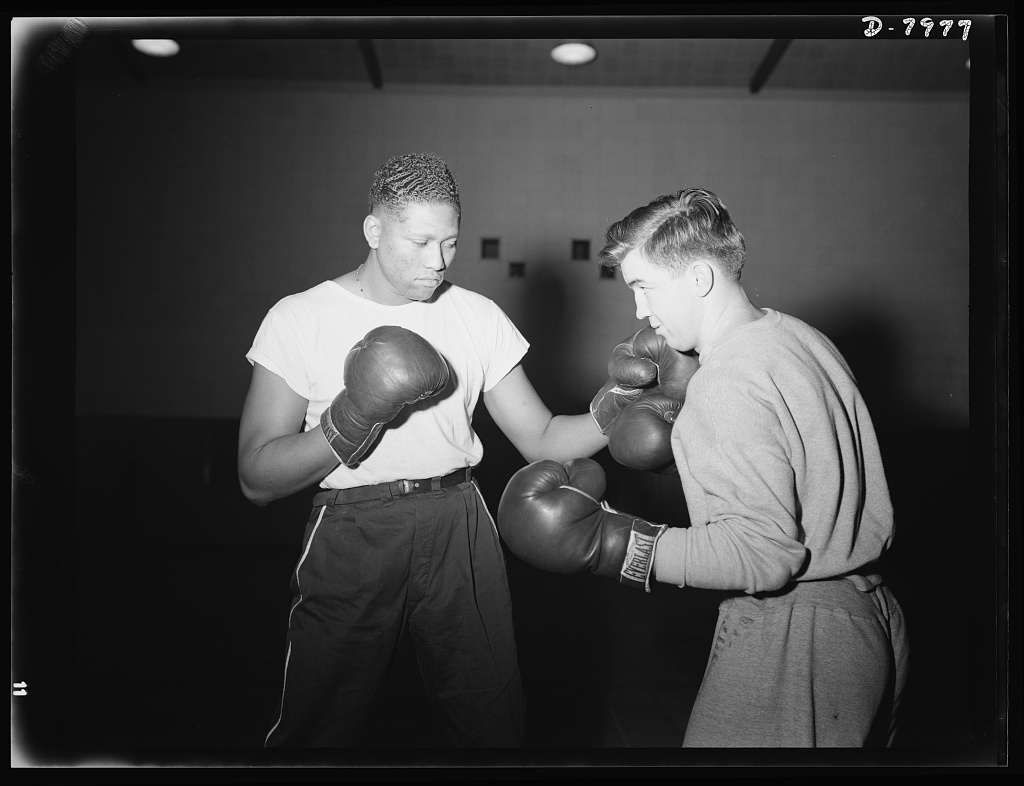

At Manhattan Beach, days were filled with classes on military customs and courtesy, marching drill, firearm practice, and more marching and exercises. Although the companies and their barracks were segregated, the camp’s common areas, mess hall, and “morale and welfare” activities were not. Sports and boxing were compulsory in the four-week intensive course at Manhattan Beach. They were also integrated. On occasion, professional boxers were employed to train the recruits.

From Manhattan Beach to sea service

service

After taking a four-week basic course, those African Americans who qualified were trained for general service ratings, such as radiomen, pharmacist mates, yeomen, coxswains, fire controlmen, and ratings in the seaman branch. Those who did not qualify were transferred for further training in preparation for assignments to Captain-of-the-Port units. For example, groups of black Coast Guardsmen were sent to the Pea Island Station after basic training for several weeks’ training in beach rescue duties. Groups of white recruits were also sent to the Pea Island for training under the black chief boatswain’s mate in charge. By August 1942, some 300 blacks had been recruited, trained, and assigned to general service duties under the new program. Meanwhile, the Coast Guard simultaneously recruited hundreds of African Americans for its Steward’s Branch.

The majority of black Coast Guardsmen in the general service served ashore under the Captain-of-the-Port offices, local district commanders, or at headquarters offices. Men in these assignments included hundreds in security and labor details, but more and more served as yeomen, radio operators, storekeepers, and the like.

Blacks were also assigned to local Coast Guard stations, including a second all-black boat station established at Tiana Beach, New York. Still other blacks participated in the Coast Guard’s widespread beach patrol operations. Organized in 1942 as outposts and lookouts against enemy infiltration of the nation’s coastlines, the patrols employed more than 11 percent of all the Coast Guard’s enlisted men. This large group included a number of all African American horse and dog patrols. In all, some 2,400 black Coast Guardsmen served in the shore establishment  .

.

Some African American enlistees who served as instructors at Manhattan Beach, were able to receive a commission. Joseph C. Jenkins went from Manhattan Beach to the officer candidate school at the Coast Guard Academy. He graduated in April 1943 as an ensign in the Coast Guard Reserve, almost a full year before blacks were commissioned in the Navy. Clarence Samuels, a warrant officer and instructor at Manhattan Beach, was commissioned as a lieutenant (junior grade). Jenkins and Samuels served as officers aboard the desegregated cutter USS Sea Cloud in 1943. In 1944, Harvey C. Russell was a signal instructor at Manhattan Beach when all instructors were declared eligible to apply for commissions. At first rejected by the officer candidate school, Russell was finally admitted at the insistence of his commanding officer. Russell graduated as an ensign and also served aboard Sea Cloud.

Manhattan Beach trainees Thompson and Hammond would both be assigned to the Coast Guard’s Boston barracks at the New Brunswick Hotel. Shortly after arriving at the hotel, Thompson and his squad were detailed to remove mortal remains from the infamous Coconut Grove Nightclub Fire of November 1942. Nearly 500 guests perished in what remains one of the largest number of lives lost to fire in U.S. history. The gruesome recovery work would take several days. Hammond was then assigned to guard bridges in Boston and Thompson patrolled Boston area beaches. At that time, the threat of German spies, and waterways infrastructure sabotage was great.

In 1943, Thompson and Hammond both volunteered to serve aboard Coast Guard Cutter Sea Cloud. The converted yacht would serve as an armed weather station vessel in the North Atlantic. Commanded by an innovative and forward-looking commander, Carlton Skinner, it had an integrated crew. Hammond served as a machinist mate and Thompson as a sonarman. In 1945, Thompson left the service as a boatswain mate first class, returning home to his family in D.C. He would work as a U.S. civil servant until he retired from a job at the U.S. State Department.

These African American officers commanded integrated enlisted seamen throughout the rest of the war. As captain of Lightship No. 115 and later of the Coast Guard Cutter Sweetgum in the Panama Sea Frontier, Samuels became the first African American officer to c ommand a U.S. ship in wartime as well as the first black to command a U.S. ship in a war zone. Harvey Russell was transferred from the integrated Coast Guard-manned USS Hoquiam to serve as executive officer on a cutter operating out of Philippines in the western Pacific, assuming command of the racially mixed crew shortly after the war.

ommand a U.S. ship in wartime as well as the first black to command a U.S. ship in a war zone. Harvey Russell was transferred from the integrated Coast Guard-manned USS Hoquiam to serve as executive officer on a cutter operating out of Philippines in the western Pacific, assuming command of the racially mixed crew shortly after the war.

At the behest of the White House, the Coast Guard also joined with the Navy in integrating its Coast Guard Women’s Reserve also known as SPARs. In the fall of 1944, it recruited five African American women for the SPARs. This was only token representation, but understandable since the SPARS ceased recruitment on Nov. 23, 1944, a few weeks after the decision to recruit African American women was announced. Nevertheless, these five women were trained at Manhattan Beach and assigned to Coast Guard district offices without regard to race.

After the War

Throughout the war, the Coast Guard had much less the concern than the other services regarding whether blacks outranked whites. As the war progressed, more and more blacks advanced into petty officer ranks. By August 1945, 965 African Americans, almost a third of their total number, were petty or warrant officers, many of them in the general service. By the last year of the war, many black petty officers could be found serving in mostly white crews and station complements. For example, a black second class pharmacist and third class signalman served aboard cutter Spencer, and a black coxswain served aboard a cutter in the Greenland Patrol. Other black petty officers were assigned to recruiting stations, LORAN stations, and as instructors at the Manhattan Beach Training Station.

Despite their small wartime numbers, African American Coast Guardsmen enjoyed a variety of assignments. The different reception accorded this small group of blacks might be explained by the Coast Guard’s tradition of black participation since the service’s founding in 1790. This progress could also be attributed to the ease with which the head of a small federal agency can reorder its policies.

of blacks might be explained by the Coast Guard’s tradition of black participation since the service’s founding in 1790. This progress could also be attributed to the ease with which the head of a small federal agency can reorder its policies.

Manhattan Beach Training Center would continue to receive and train Coast Guard recruits until 1950. A few years later, the property was transferred to the U.S. Air Force. From 1954 to 1959, the Air Force used the post as a staging area and point of departure for Air Force members going overseas. After a brief period of use by the U.S. Merchant Marine and the Department of the Army, the location was returned to local government. Since 1966, the site has hosted Kingsborough Community College, a branch of the City University of New York.