Navy Cross Medal citation for Raymond J. Evans, 1943:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Chief Signalman Raymond J. Evans, United States Coast Guard, for extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty in action against the enemy while serving as a member of the crew of a HIGGINS boat assisting in the rescue of a group of Marines of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, FIRST Marine Division, who

extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty in action against the enemy while serving as a member of the crew of a HIGGINS boat assisting in the rescue of a group of Marines of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines, FIRST Marine Division, who  had become surrounded by enemy Japanese forces on a beachhead of Guadalcanal, Solomons Islands, on 27 September 1942. Although he knew that his boat was to be used for the purpose of drawing enemy fire away from other craft evacuating the trapped Marines, Chief Signalman Evans, with utter disregard for his own personal safety, volunteered as a member of the crew. Gallantly remaining at his post during the entire evacuation and with every other member of his crew killed or wounded, he maintained control of the boat with one hand on the wheel and continued to fire his automatic machine gun with the other, until the last boat cleared the beach. By his great personal valor, skill and outstanding devotion to duty in the face of grave danger, he contributed directly to the success of his mission by saving the lives of many who otherwise might have perished.

had become surrounded by enemy Japanese forces on a beachhead of Guadalcanal, Solomons Islands, on 27 September 1942. Although he knew that his boat was to be used for the purpose of drawing enemy fire away from other craft evacuating the trapped Marines, Chief Signalman Evans, with utter disregard for his own personal safety, volunteered as a member of the crew. Gallantly remaining at his post during the entire evacuation and with every other member of his crew killed or wounded, he maintained control of the boat with one hand on the wheel and continued to fire his automatic machine gun with the other, until the last boat cleared the beach. By his great personal valor, skill and outstanding devotion to duty in the face of grave danger, he contributed directly to the success of his mission by saving the lives of many who otherwise might have perished.

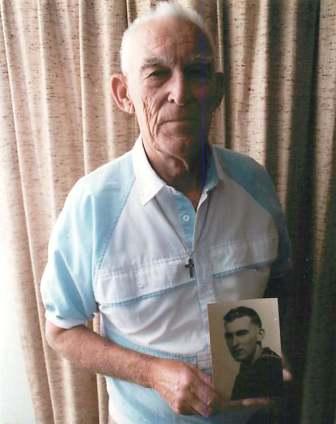

Coast Guard hero Raymond J. Evans was a writer, a self-proclaimed wordsmith, high school basketball and football player with a “glass jaw,” and no affinity for boxing. He was also a Coast Guard hero and a great friend to the late Signalman 1st Class Douglas Munro, the service’s only Medal of Honor recipient.

At the age of 18, Evans enlisted at the recruiting station alongside Douglas Munro, Sep. 18, 1938. This was the beginning of a deep friendship between the two future Coast Guard heroes who became known as the “Gold Dust Twins.”

Starting out as an apprentice seamen earning $21 a month, Evans began a routine of mowing the base lawn and cleaning and servicing aircraft at Air Station Port Angeles. Not long after, Evans and Munro volunteered to fill two open billets aboard Coast Guard Cutter Spencer, then en route from Valdez, Alaska, to Staten Island, New York. Evans and Munro served aboard Spencer until early 1941, both earning the signalman rating while aboard. After World War I, the Coast Guard had no need of signalmen, but as  World War II loomed closer, the service brought the rating back. The rating allowed Coast Guard units to communicate with the Navy through light signals, running flags, and semaphore.

World War II loomed closer, the service brought the rating back. The rating allowed Coast Guard units to communicate with the Navy through light signals, running flags, and semaphore.

When word spread that men were needed to fill out the crew aboard the Coast Guard-manned transport USS Hunter Liggett, Evans and Munro pleaded with Spencer’s executive officer to allow them to transfer. The so-called “Gold Dust Twins” were reassigned to the transport, which was bound for the South Pacific and the war front.

Early in summer 1942, while laying over in New Zealand, Munro and Evans received assignment to the USS Charles McCawley, flagship of Navy Rear Adm. Richmond Turner. Evans returned to the Liggett before the assault on Guadalcanal, but Munro stayed behind aboard the McCawley. From McCawley, he helped land Marines on the hotly contested beaches of Tulagi and remained on the island with a Marine guard to set-up ship-to-shore communications using an Aldis lamp and Morse code.

Later, Munro transferred to Guadalcanal, where he and Evans were the senior enlisted men at Guadalcanal’s Coast Guard-manned naval operating base (NOB) named NOB Cactus. They served as enlisted leadership at the base under the command of Coast Guard Lt. Cmdr. Dwight Dexter. For their accommodations, they built a makeshift five-by-eight foot shelter of packing crates at the base of the coconut-log signal tower and enclosed it with a tent roof.

In addition to its logistical support mission, NOB Cactus served as an important communications hub between the Marines and offshore vessels. During the day, Munro and Evans signaled by Aldis lamp from the coconut-log tower to Allied ships. At night, the Navy command prohibited signaling because the light attracted the attention of enemy warships and submarines. Evans and Munro also used “walkie talkie” two-way radios and Morse code to communicate with the landing craft.

During the initial stages of the Guadalcanal campaign, the waters of Iron Bottom Sound concealed stealthy Japanese submarines. With few Allied patrol craft available to defend against this silent but deadly menace, NOB Cactus provided nightly anti-submarine patrols. NOB’s patrols comprised three LCPs, each responsible for a different part of the sound. The crews fitted their boats with depth charges set for 50 feet, a depth that could have sunk an enemy sub as well as the landing craft. During an initial patrol,  a Japanese mini-sub surfaced near Evans’ LCP and heard the landing craft’s loud engine. The enemy sub commander turned a flood lamp on the source of the noise to see the depth-charge equipped landing craft, and he crash-dived his sub. Evans ordered the coxswain to speed toward the sub’s last seen position to drop the depth charge; however, shocked by the search light, the coxswain instinctively sped away from the light. They had missed the opportunity to become the world’s first landing craft to sink a submarine!

a Japanese mini-sub surfaced near Evans’ LCP and heard the landing craft’s loud engine. The enemy sub commander turned a flood lamp on the source of the noise to see the depth-charge equipped landing craft, and he crash-dived his sub. Evans ordered the coxswain to speed toward the sub’s last seen position to drop the depth charge; however, shocked by the search light, the coxswain instinctively sped away from the light. They had missed the opportunity to become the world’s first landing craft to sink a submarine!

Referred to as the “taxis  to hell,” Coast Guard-manned watercraft supported regular marine patrols and reconnaissance missions along Guadalcanal’s shoreline and to other islands. In September, NOB landing craft also began supporting reconnaissance missions composed of native scouts and marines. British Colonial Forces officers led these nighttime operations and Evans oversaw their water transportation.

to hell,” Coast Guard-manned watercraft supported regular marine patrols and reconnaissance missions along Guadalcanal’s shoreline and to other islands. In September, NOB landing craft also began supporting reconnaissance missions composed of native scouts and marines. British Colonial Forces officers led these nighttime operations and Evans oversaw their water transportation.

U.S. Marine strategists not only planned frontal and flank attacks against enemy positions, they occasionally landed troops on beaches behind enemy lines. NOB Cactus provided water transportation for these amphibious landings. For example, at about 1:00 p.m., on Sunday, Sep. 27, Munro and Evans supervised a flotilla of NOB Cactus landing craft transporting Lt. Col. Lewis “Chesty” Puller’s First Battalion, Seventh Marine Regiment, of 488 officers and men. The NOB Cactus watercraft landed the marines near Point Cruz, a Japanese stronghold located along the north shore of Guadalcanal four miles due west of NOB Cactus.

After landing the Marines, Munro took the NOB Cactus fleet back to base, but Evans remained behind with an LCP positioned close to shore to take-off wounded marines. Enemy machine gun fire raked the landing craft striking Navy coxswain Sam Roberts in the neck. With Roberts bleeding badly, Evans sped his damaged boat back to NOB Cactus to seek medical attention. Evans landed Roberts at the NOB waterfront, but the coxswain passed away the next day. Samuel B. Roberts would posthumously receive the Navy Cross Medal and become even more famous for his namesake destroyer escort that fought off the Japanese fleet at the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

By 3:30 that afternoon, Gen. Alexander Vandergrift’s First Marine Division command post called Dexter’s NOB headquarters. A numerically superior Japanese force at Point Cruz armed with mortars, machine guns and anti-tank guns had ambushed Puller’s battalion, inflicting heavy loses. The NOB boat flotilla had to evacuate the marines as soon as possible. The commanding officer of NOB Cactus, Dexter, stepped out of the headquarters shack and shouted down to Munro and Evans on the waterfront, “Will you two lead these boats to take them off?” and Munro’s rapid response was “Hell, yes.” Evans recalled later, “The three of us had done duty together for a long time, and I’m sure the commander knew the answer before he asked.”

By about 4:00 p.m., Evans, Munro and Navy coxswain Walter Bennett had disembarked an LCP to lead the NOB Cactus flotilla back to Point Cruz with Munro serving as officer-in-charge. To locate elements of the beleaguered Marine battalion, Munro and E vans steered their LCP up to the beach under fire. After making contact with the Marines, they maneuvered the boat into an exposed position to provide cover for the evacuation and draw the enemy’s fire. Using their dual .30 caliber equipped LCP as a floating machine gun nest, Munro and his shipmates fought Japanese machine gunners at close range and orchestrated the evacuation of the Marines.

vans steered their LCP up to the beach under fire. After making contact with the Marines, they maneuvered the boat into an exposed position to provide cover for the evacuation and draw the enemy’s fire. Using their dual .30 caliber equipped LCP as a floating machine gun nest, Munro and his shipmates fought Japanese machine gunners at close range and orchestrated the evacuation of the Marines.

In the span of only 30 minutes, all the Marines except the dead were safely loaded onto the waiting NOB boats. The flotilla of landing craft began the four-mile return trip to NOB Cactus, but Evans and Munro remained behind to assist one of the Landing Craft-Tanks (LCT) grounded on the beach. While they helped pull the LCT clear, the Japanese set-up a machine gun on the beach and raked Munro’s LCP. The enemy fusillade wounded the entire crew except Evans. Bennett suffered non-fatal wounds from the incoming rounds and later received the Navy Cross Medal for his role in the action. Directing the landing craft and manning his air-cooled .30 caliber Lewis machine gun, Munro suffered a serious neck wound as had Roberts in the initial landings.

Munro’s boats had evacuated all survivors of Puller’s battalion, including 25 wounded. Unfortunately, Munro had taken a bullet to the neck at the base of his skull. Evans failed to realize his friend’s situation until another man motioned him forward to the bow, where Munro lay slumped down in his forward gun position. Evans knelt down beside Munro, who asked, “Did we get them all off? Evans later recounted Munro’s final moment: “And seeing my affirmative nod, he smiled with that smile I knew and liked so well, and then he was gone.”

Before rotating back to the States, Evans and LDR Dexter paid their respects to Doug Munro at Guadalcanal’s military cemetery, hallowed ground the Americans had cleared of the jungle and the Japanese. Evans then flew from Guadalcanal to Noumea, New Caledonia, for an audience with Adm. William “Bull” Halsey. Halsey advanced Evans from first class t o chief signalman. In May 1943, he was awarded the Navy Cross Medal for the Point Cruz evacuation.

o chief signalman. In May 1943, he was awarded the Navy Cross Medal for the Point Cruz evacuation.

In 1943, Evans was also offered a commission to become a communications officer despite lacking a college degree. “With only a high school education and thanks to wartime conditions requiring extreme measures to provide leadership, I was fortunate to be chosen to serve in a commissioned status and to be retained with other temporary service officers in the active duty commissioned ranks,” Evans said in 2000. Evans served the rest of his career as a commissioned officer, retiring as a commander in 1962. “I enjoyed every minute of my 23 plus years which included in excess of 12 years of sea duty.”

Ray Evans died May 30, 2013. He was awarded the Navy Cross Medal, Presidential Unit Citation Ribbon with one battle star, Commandant’s Letter, the American Defense Service Medal with one battle star, American Campaign Medal, the European-Africa-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with five battle stars and the Coast Guard Good Conduct Medal, among others. He is also the namesake of a Fast Response Cutter.

“We just did a job,” recalled Evans in an interview in 1999. “We were asked to take them over there, and we were asked to bring them back off from there, and that’s what we did. That’s what the Coast Guard does. We do what we’re asked to do.” In Evans’s opinion, “Heroes are no special people, they are just regular persons, placed in a position of peril where they rise above their fear to do the job assigned to them or what needs to be done to gain success.”