I am very pleased to forward a Purple Heart Medal and Certificate to you for service at Guadalcanal in August of 1942. Men such as you who have made great contributions to the grand heritage of the Coast Guard make me proud to be a member of our service.

Capt. James Parent, Office of Personnel, U.S. Coast Guard, 1984

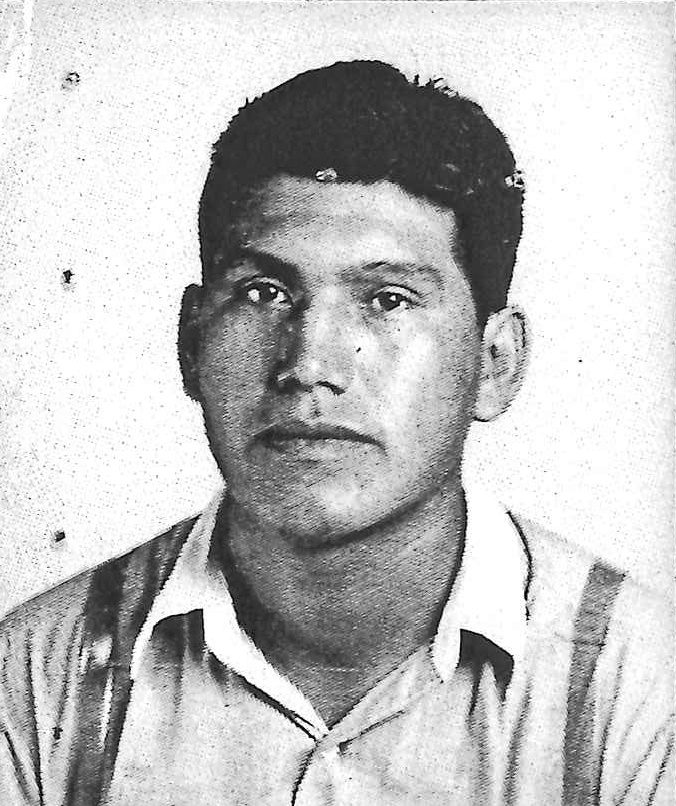

Native American Joseph Robert Toahty hailed from a large and patriotic family. At a time when Native Americans were denied many basic rights, he and six brothers fought valiantly in World War II. In 1984, he told a newspaper reporter, “At one time, my mother had a son in every branch of the service.”

Native American Joseph Robert Toahty hailed from a large and patriotic family. At a time when Native Americans were denied many basic rights, he and six brothers fought valiantly in World War II. In 1984, he told a newspaper reporter, “At one time, my mother had a son in every branch of the service.”

Joseph Toahty was born in Oklahoma in 1919. He was half Pawnee and half Kiowa Indian and inherited the name Le-Tuts-Taka (“White Eagle”) from his grandfather, Pawnee Chief White Eagle, who served honorably as a U.S. Army scout during and after the Civil War. Joseph Toahty was also a graduate of the well-known Haskell Institute for Native Americans in Lawrence, Kansas. After graduating from Haskell, he worked as a carpenter at the Army base at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, and served in the Kansas National Guard.

In June 1941, six months before the U.S. entered the war, Toahty enlisted in the Coast Guard. During his ti me in the service, Toahty and the Coast Guard would establish a record of firsts. After enlisting, he became the first Pawnee Indian to go to sea. During the war, Toahty also became the first Native American to participate in a U.S. naval offensive operation and the first to set foot in enemy territory.

me in the service, Toahty and the Coast Guard would establish a record of firsts. After enlisting, he became the first Pawnee Indian to go to sea. During the war, Toahty also became the first Native American to participate in a U.S. naval offensive operation and the first to set foot in enemy territory.

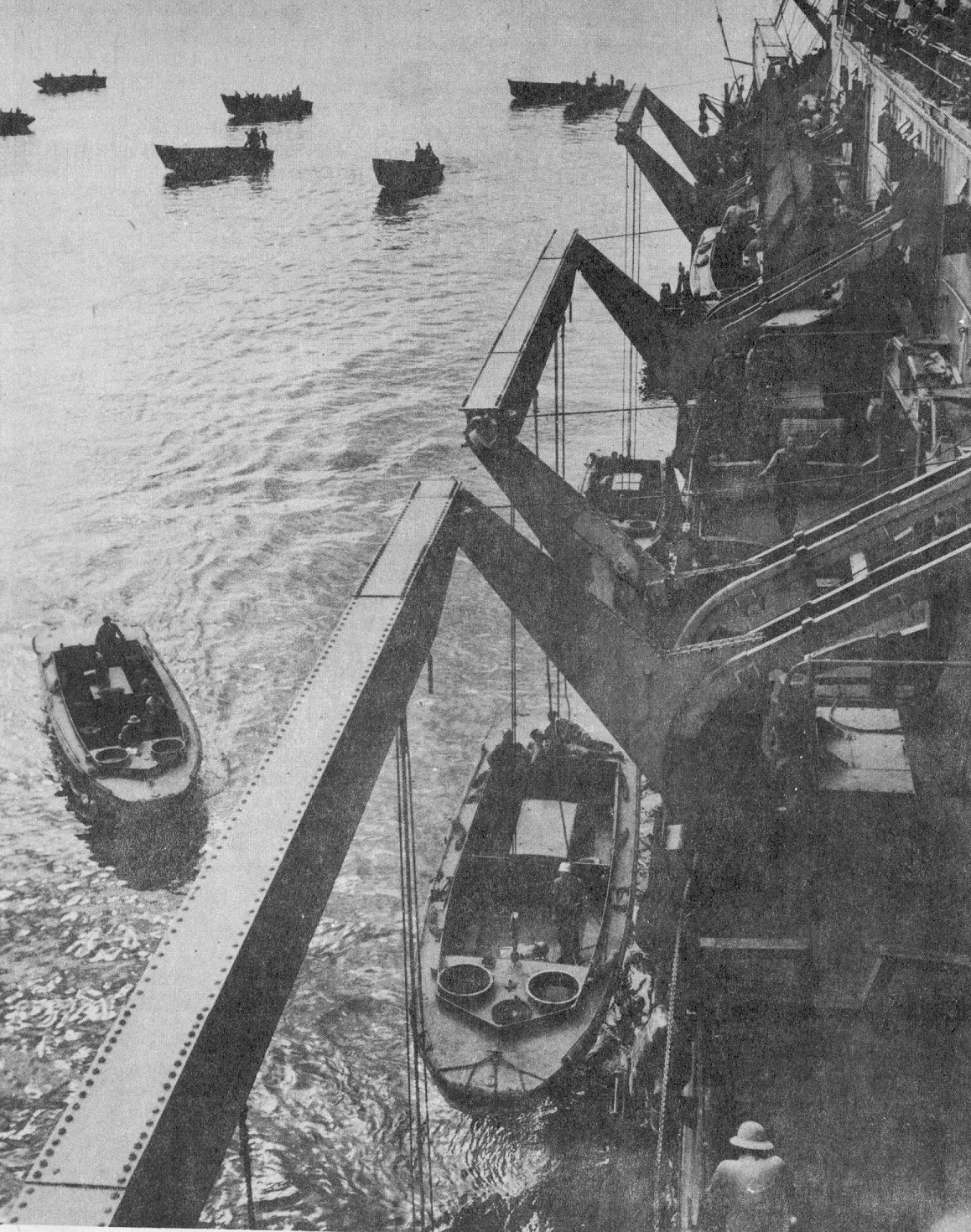

In 1942, Toahty deployed to Guadalcanal, the Allies’ first amphibious operation of World War II. At Guadalcanal, the Coast Guard established its own Naval Operating Base (NOB) for the first time in its history. The code name for this Coast Guard-run navy base was NOB “Cactus.” At its peak, NOB Cactus included about 30 landing craft, vehicle, personnel (LCVPs), also known as Higgins Boats, and a dozen bow-ramped tank lighters. Fifty officers and enlisted men ran the base. This crew included Medal of Honor recipient Douglas Munro, Navy Cross recipient Ray Evans, Silver Star recipient Dwight Dexter and 23-year-old Purple Heart recipient Joseph  Toahty. All would receive the Presidential Unit Citation for “outstanding gallantry” reflecting “courage and determination ... of an inspiring order.”

Toahty. All would receive the Presidential Unit Citation for “outstanding gallantry” reflecting “courage and determination ... of an inspiring order.”

NOB Cactus’s primary mission was to ferry troops and supplies from transport ships to the beaches of Guadalcanal. However, Toahty’s unit did much more than merely supplying the troops. It provided an important radio and communications link between land  forces and offshore vessels. Its craft navigated the waters off Guadalcanal and islands as far as 60 miles away to land Marines and retrieve them when necessary. Its boats inserted reconnaissance teams led by British Colonial Forces officers behind enemy lines. In the aftermath of near daily aerial dogfights and naval battles, NOB watercraft took to open water to retrieve American survivors and Japanese prisoners. For a time, NOB personnel even fitted their landing craft with depth charges and conducted nightly anti-submarine patrols. Coast Guard personnel also helped defend Marine Corps positions by supplying artillery pieces and providing infantry support.

forces and offshore vessels. Its craft navigated the waters off Guadalcanal and islands as far as 60 miles away to land Marines and retrieve them when necessary. Its boats inserted reconnaissance teams led by British Colonial Forces officers behind enemy lines. In the aftermath of near daily aerial dogfights and naval battles, NOB watercraft took to open water to retrieve American survivors and Japanese prisoners. For a time, NOB personnel even fitted their landing craft with depth charges and conducted nightly anti-submarine patrols. Coast Guard personnel also helped defend Marine Corps positions by supplying artillery pieces and providing infantry support.

NOB Cactus included an odd collection of coconut plantation buildings, homemade shacks and tents, and log-reinforced dugout shelters. The Coast Guard members stationed there used the dugout bomb shelters frequently due to regular enemy bombing, naval shelling, and artillery fire. During one of these bombardments, Toahty and seven others took cover in one of the bomb shelters. The large foxhole suffered a direct hit, killing all occupants except Toahty and one other survivor. After regaining consciousness, Toahty suffered from a severe concussion with heavy bleeding from his nose, ears, and mouth. After visiting the Marine Corps infirmary, he received treatment and returned to duty with no record of his wound.

In January 1943, Toahty rotated off the island with battle weary elements of the Coast Guard and First Marine Division. When he left the island, the battle for Guadalcanal had entered its sixth month. By then, the Marines had secured the Allied position on the island and elements of the U.S. Army relieved them. Toahty redeployed to New Zealand where native Polynesians hosted a day-long ceremony in his honor. According to Toahty, he “was the first American Indian they had ever seen.” Toahty recalled that the natives “treated me as if I were a king; and in fact one of the dances they performed was reserved strictly for royalty. I hated to leave that village.”

Like many who served on Guadalcanal, Toahty had contracted malaria. His case was particularly severe and led to serious illness and hospitalization. But malaria didn’t stop Toahty. He extended his enlistment two more years and returned home from the Pacific to serve at various units stateside. He also became a War Bond hero, participating in drives across the U.S. For example, he participated in the “Back Salerno Airmada” with other heroes and celebrities, such as movie star William “Hopalong Cassidy” Boyd. He later toured with Iwo Jima marine hero Ira Hayes, Medal of Honor recipient celebrity Audie Murphy and the “Hollywood Cavalcade” of m

Like many who served on Guadalcanal, Toahty had contracted malaria. His case was particularly severe and led to serious illness and hospitalization. But malaria didn’t stop Toahty. He extended his enlistment two more years and returned home from the Pacific to serve at various units stateside. He also became a War Bond hero, participating in drives across the U.S. For example, he participated in the “Back Salerno Airmada” with other heroes and celebrities, such as movie star William “Hopalong Cassidy” Boyd. He later toured with Iwo Jima marine hero Ira Hayes, Medal of Honor recipient celebrity Audie Murphy and the “Hollywood Cavalcade” of m ovie stars. In 1945, after suffering almost monthly attacks from malaria, he received an honorable medical discharge.

ovie stars. In 1945, after suffering almost monthly attacks from malaria, he received an honorable medical discharge.

Guadalcanal was one of the most decorated combat operations in Coast Guard history. President Franklin Roosevelt awarded the Presidential Unit Citation (PUC) to the “First Marine Division, Reinforced” with the word “Reinforced” honoring support units, such as the Coast Guard members serving on the island. In addition to the PUC (which equates to the Navy Cross Medal on an individual basis), Toahty was promoted from fireman first class to motor machinist’s mate second class. In 1984, the Coast Guard presented Toahty the four campaign medals he earned for wartime service and the long-overdue Purple Heart Medal for wounds suffered from the direct hit on his bomb shelter at Guadalcanal.

Joseph Toahty lived and worked in Oklahoma City after he left the service. He was active in Native American and military organizations and, in retirement, he helped Vietnam veterans with Agent Orange health benefit claims. He passed away in Oklahoma City in 1997 at the age of 77. Toahty is among the thousands of distinguished Coast Guard combat veterans who served in the long blue line.