Born in Providence, R.I., on Aug. 19, 1922, Fletcher P. Burton, Jr., also known as “Fletch,” was the youngest of four children and an only son. The family lived in a wealthy section of East Providence in a home with eight bedrooms and 10 baths. In addition to the six Burton family members, the household included a nanny, maid, and cook.

Born in Providence, R.I., on Aug. 19, 1922, Fletcher P. Burton, Jr., also known as “Fletch,” was the youngest of four children and an only son. The family lived in a wealthy section of East Providence in a home with eight bedrooms and 10 baths. In addition to the six Burton family members, the household included a nanny, maid, and cook.

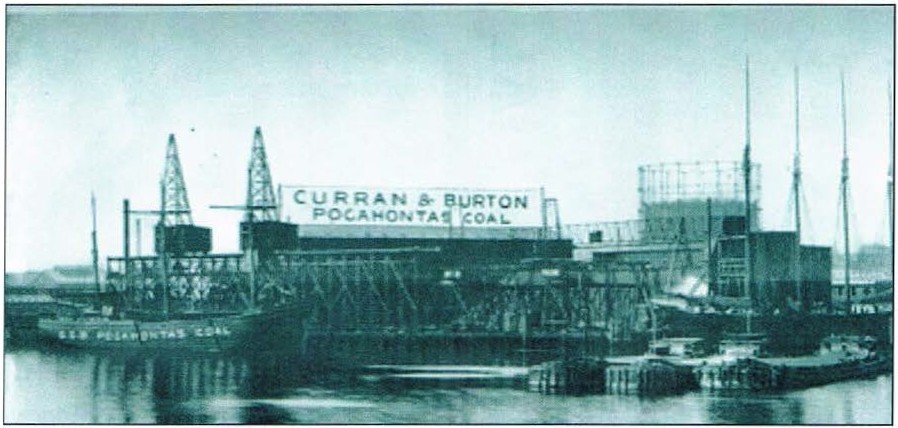

As the president of a major coal-merchandising firm, Fletch’s father was a prominent member of the Providence business community. The Curran & Burton Company had offices in downtown Providence as well as industrial facilities on the Providence River waterfront to which sub-bituminous coal was shipped from the Pocahontas Mine in southwest Virginia via rail to the seaport of Norfolk, Va. Because the coal from the mine was of very high quality, the U.S. Navy desired it greatly due to its smokeless nature.

During his early years, Fletch attended Moses Brown School in Providence before enrolling at the Taft School in Watertown, Conn., for his senior year of high school. At Taft, Fletch was one of the most respected and popular boys in the school. His senior yearbook states: “he was one of the most likable boys ever to attend Taft. Popular and exceedingly hardworking . . . Fletch is everyone’s friend, always ready to lend a helping hand.” He was a decorated track and field athlete who competed in the strength events, including shotput, discus, and hammer throw. In the hammer throw, he set the New England Prep School Track Meet record. Fletch next attended Dartmouth College for a year and enlisted in the Coast Guard during his sophomore year.

After basic training, Fletch was assigned to the USS LCI(L)-94 (Landing Craft Infantry/Large). The ship was a 158-foot troop carrier with a Coast Guard crew of four officers and 26 enlisted men. The LCIs were the smallest Allied seagoing ships of World War II. Fletch was a seaman first class whose battle station was in the pilothouse. The ship’s armament included four 20 m illimeter guns, with one forward, one amidships, and two aft, as well as two 50-caliber machine guns. Crews joked that LCI stood for “Lousy Civilian Idea.”

illimeter guns, with one forward, one amidships, and two aft, as well as two 50-caliber machine guns. Crews joked that LCI stood for “Lousy Civilian Idea.”

On D-Day, June 6, 1944, the 94 was part of the Coast Guard’s Flotilla 10 assigned to transporting troops to Omaha Beach one hour after the first landings. LCI vessels were relatively large landing craft compared to the smaller wooden Higgins Boats built in large numbers for the war. The 94 w as constructed in Galveston, Texas, in 1942 and, in 1943, it crossed the Atlantic from Norfolk Naval Base to the Mediterranean where it was put into service during the North African and Sicily invasions. With its flat bottom, an LCI was designed to deliver troops directly to the beach. However, given that there was no keel to hold an LCI steady while underway, even the slightest sea would toss it from side to side.

as constructed in Galveston, Texas, in 1942 and, in 1943, it crossed the Atlantic from Norfolk Naval Base to the Mediterranean where it was put into service during the North African and Sicily invasions. With its flat bottom, an LCI was designed to deliver troops directly to the beach. However, given that there was no keel to hold an LCI steady while underway, even the slightest sea would toss it from side to side.

LCI-94’s mission was to land nearly 180 troops on Omaha Beach in the second wave of the assault. These men included 42 medically trained members of Company B, 104th Medical Battalion; 36 men of the 29th Military Police (MPs); and 101 soldiers of the 112th Combat Engineers. Initially, Company B’s job was to give first aid to and evacuate the first casualties on Omaha Beach. The MPs were to bring order to the chaos on the beaches and the engineers were to clear mines and assist with removing obstacles from the assault lanes.

The skipper of the 94 was 27-year-old Lt. Gene Gislason . Despite his relative youth, Gislason was a colorful person and as experienced mariner known affectionately by his crew as “Popeye.” A native of Sturgeon Bay, Wisc., his maritime career began in merchant ships on the Great Lakes. After joining the Coast Guard in 1942, he commanded the 94 in amphibious landings at North Africa and Sicily and Salerno, Italy.

. Despite his relative youth, Gislason was a colorful person and as experienced mariner known affectionately by his crew as “Popeye.” A native of Sturgeon Bay, Wisc., his maritime career began in merchant ships on the Great Lakes. After joining the Coast Guard in 1942, he commanded the 94 in amphibious landings at North Africa and Sicily and Salerno, Italy.

Fletch’s shipmate, 19-year-old motor machinist mate Charles Jarreau from Baton Rouge, La., recounted the time leading up to the D-Day mission. Jarreau described Gislason’s unorthodox leadership style as captain of the 94 and how Fletch and his shipmates spent their last hours on the LCI in Weymouth Bay before heading out to sea. According to Jarreau: “the captain’s rules were his rules and not the Navy’s. He did not like the Navy’s rules.” Two days before the soldiers were to come aboard the 94, Gislason told Jarreau: “there’s nobody going to leave this ship [before D-Day], so you go out and get the liquo r you want and we are going to have a party.” The party, according to Jarreau, “started at 0700 and boy, at the end of the day, everybody was just crapped out, but it sure relieved the tension. After a night’s sleep, we sobered up and started taking troops board.” Therefore, thanks to his captain’s very un-Navy-like policies, so

r you want and we are going to have a party.” The party, according to Jarreau, “started at 0700 and boy, at the end of the day, everybody was just crapped out, but it sure relieved the tension. After a night’s sleep, we sobered up and started taking troops board.” Therefore, thanks to his captain’s very un-Navy-like policies, so me of Fletch’s last hours were spent “tying one on” with his buddies before the D-Day run.

me of Fletch’s last hours were spent “tying one on” with his buddies before the D-Day run.

After the long turbulent journey across the English Channel, the flat-bottomed LCI neared the coast of France. By that time, most of the soldiers became seasick many vomiting into their helmets. At 7:15 a.m., as the ship approached the hostile beach, general quarters sounded as shrapnel and machine gunfire clattered against the ship’s hull and smoke poured from burning vessels they passed on the way to the landing site.

The 94 and its sister-ships, LCIs 91 and 92, approached Omaha Beach within a 1,000 yards of one another to the sector designated Dog Red. Despite earlier shelling and bombing of the landing area, mines and obstacles remained largely intact. At 7:40 a.m., the bow of the LCI-92 received German gunfire. The enemy then hit the LCI amidships and it exploded. Those not killed instantly were thrown into the surf slick with burning oil and German gunners raked them with machine gun fire. LCI 91 was in the same sector and, as the ship approached the beach, it was hit with rifle and machine gunfire while attempting to maneuver through obstacles. The 91 then struck a teller mine and was hit with 88 millimeter rounds causing a blast that lifted the 91 completely out of the water. A sheet of flames shot up from the forward hold. Forty-one soldiers in the forward troop compartment were trapped in the fiery furnace and most killed instantly. Seein

The 94 and its sister-ships, LCIs 91 and 92, approached Omaha Beach within a 1,000 yards of one another to the sector designated Dog Red. Despite earlier shelling and bombing of the landing area, mines and obstacles remained largely intact. At 7:40 a.m., the bow of the LCI-92 received German gunfire. The enemy then hit the LCI amidships and it exploded. Those not killed instantly were thrown into the surf slick with burning oil and German gunners raked them with machine gun fire. LCI 91 was in the same sector and, as the ship approached the beach, it was hit with rifle and machine gunfire while attempting to maneuver through obstacles. The 91 then struck a teller mine and was hit with 88 millimeter rounds causing a blast that lifted the 91 completely out of the water. A sheet of flames shot up from the forward hold. Forty-one soldiers in the forward troop compartment were trapped in the fiery furnace and most killed instantly. Seein g all this, it was clear that the same fate awaited his ship if

g all this, it was clear that the same fate awaited his ship if  he kept on that same heading, so Gislason maneuvered his ship around numerous mined obstacles. Gislason turned east to a point between Dog Red and Easy Green beaches near Saint Laurent and Colleville-sur-Mer. At 7:45 a.m., 94’s troops were called to their beaching stations and, at two minutes later, they began wading toward the beach in shoulder-high water with even higher swells.

he kept on that same heading, so Gislason maneuvered his ship around numerous mined obstacles. Gislason turned east to a point between Dog Red and Easy Green beaches near Saint Laurent and Colleville-sur-Mer. At 7:45 a.m., 94’s troops were called to their beaching stations and, at two minutes later, they began wading toward the beach in shoulder-high water with even higher swells.

Many of the soldiers swam part of the way to shore sometimes underwater. At that moment, with the 94 beached, three 88 millimeter artillery rounds hit the LCI’s pilothouse, killing Fletcher and two of his shipmates and wounding three others. The pharmacist mates immediately went to work on those injured by the pilothouse blast where blood and flesh had been splattered everywhere. Mercifully, Fletch was killed instantly by the concussion, but his shipmate, Seaman First Class Jack DeNunzio, had both legs and part of his stomach blown away. He was given plasma but died 15 minutes later. Seaman First Class August Buncik also died. With his uniform covered with the body parts of his crewmembers, Gislason was in tears.

As the crippled 94 was about to leave the beachhead, the celebrated Life Magazine photographer, Robert Capa, requested permission to come aboard. He had famously landed on Omaha Beach with the second wave and waded out to the ship with his cameras held over his head. Just moments before Capa boarded, Fletch and his shipmates  had been killed and one of Capa’s iconic photos captured medics on the deck of the ship attending to Fletch’s wounded shipmates.

had been killed and one of Capa’s iconic photos captured medics on the deck of the ship attending to Fletch’s wounded shipmates.

Because of the shelling, the ship’s communications and steering were knocked out and only one of the two screws functioned. Another landing craft became entangled with a line from the 94. In addition, even though unloading the troops and their equipment had lightened the ship’s load, the crew still had great difficulty in freeing the vessel from the sand. After sitting on the beach under heavy fire for 50 minutes, the damaged and inoperative port ramp was finally cut away and the skipper was able to hand-steer the ship off the beach and return to its mother ship. Of the nine LCIs that successfully beached on Dog Red that day, only four remained functional. In recognition of this action, Gislason received the Silver Star Medal for his outstanding leadership and seamanship during the landings.

The bodies of Fletch and his deceased shipmates were put aboard an LST with other casualties for transport to the Coast Guard attack transport USS Samuel Chase. They were later buried back on the beach before eventually being reinterred in the American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. Fletch was just 21 when he died. He was one of 15 Coast Guardsmen killed on D-Day. He was also one of 23 members of the Dartmouth class of 1945 who decided to enlist prior to graduation and lost their lives in the war. His October 1944 Dartmouth Alumni Magazine obituary mentions that “he was one of those lads who couldn’t wait to get into service.”