Editor’s note: This article initially published Nov. 24 in the Commandant’s Bulletin Magazine.

The town of Valdez, Alaska, fell behind the U.S. tanker Williamsburgh. Full of oil, the ship headed for Texas. The bridge crew sighed relief—one more successful trip through the narrow channel. Midnight was approaching, bringing in Saturday, Oct. 4, 1980, and what the crew thought would be a quiet, normal day.

The town of Valdez, Alaska, fell behind the U.S. tanker Williamsburgh. Full of oil, the ship headed for Texas. The bridge crew sighed relief—one more successful trip through the narrow channel. Midnight was approaching, bringing in Saturday, Oct. 4, 1980, and what the crew thought would be a quiet, normal day.

Not far away, the games of the first night at sea were over aboard the luxury cruise liner, Prinsendam. The ship left Vancouver on a 30-day cruise to [Southeast Asia]—first stop Singapore. Some were asleep, and some were trying to fall asleep. Some had closed the bar and were just heading for their cabins.

At about 1 a.m., passengers on the ship were jarred from their sleep.

Fire had started in the engine room. Alarms and bells rang, and the sound of explosions and the smell of smoke filled the passageways. Prinsendam had stopped dead.

Firefighting pumps were among the first equipment knocked out by the fire. With carbon dioxide and foam extinguishers, the Indonesian crew fought the blaze. The fire spread. The ship broadcast the international distress call a half-hour later.

“SOS! SOS! This is the Prinsendam. We have fire in the engine room and we are dead in the water. SOS!”

The call reached the Coast Guard in the North Pacific and Radio Operator Jim Pfister on Tanker Williamsburgh.

Everything moved into action. Coast Guard District Seventeen air stations were alerted. Cutters got under¬way. Being closest, Williamsburgh moved toward the stricken Dutch liner. Aboard Prinsendam, passengers and crew were herded into the lounge and on the weather decks in bare feet, pajamas, and whatever clothes were handy.

While the crew fought the fire, the passen¬gers waited. They were told everything would be under control soon. Most of them were elderly Americans. Not many young people could afford the $3,000 to $6,000 travel fare in 1980.

The cruise staff entertainers strolled the deck performing selections from the musical “Oklahoma” and other shows to ease the tension.

Some passengers were complaining about not having a chance to get their clothes or valuables from their cabins. At 3:30 a.m., they knew why. The fire had spread to the dining room, several decks above the engine room, and to the cabins located in between.

Captain Cornelius Wabeke told the Coast Guard he had lost water pressure and most of his firefighting capabilities. Firefighting pumps were airdropped and the service began assembling more equipment.

In Yakutat, Alaska, a staging area was being built to support whatever disaster might lay ahead. Air Stations Kodiak and Sitka were supplying two helicopters each; and the Canadians were adding two helicopters and two fixed-wing aircraft. The U.S. Air Force in Anchorage was sending another helicopter.

Medical, firefighting and logistics personnel and equipment were assembling with the aircraft at Yakutat.

Wabeke gave the the order to “abandon ship” shortly after 5 a.m. He and a nearly 50-man crew would stay behind with a Coast Guardsman who was airdropped to assist with the new fire¬ fighting equipment. The ship was beginning to list, and the captain suspected that lower decks were taking on water. The almost 500 passen¬gers and other crewmembers had to leave.

Passengers and crew jammed into the life¬boats, sometimes 80 or more in a single boat. Some married couples were separated in the scramble. No one had a chance to change. Many were still in pajamas and bare feet with drapes from the lounge as their blankets, or sweaters from the gift shop for wraps. With only six or seven lifeboats and two or three life rafts free, fear likely ran among the more than 500 people.

The Williamsburgh was still two-and-a-half hours away but the sea was finally calm. It had been rough since dinner.

David Levin, a 77-year-old pas¬senger from California, managed to don a purple jogging suit before going on deck. “When we began [getting into the boats], we were singing. The stars were shining and the sky was clear,” he said. Levin said they started-off singing “Row Your Boat.”

Some lifeboats had problems releasing from the ship. Lines got tangled, and boats slammed into the side of the ship. In one case, a boat was being lowered on top of another. The crew had not counted on the boat engines going bad so quickly, or several that had broken rudders.

An ex-Coast Guardsman and New Jersey magnate, Fairleigh Dickinson, Jr., took “captainship” of his lifeboat. He rigged a sea anchor to steer the lifeboat. His wife, Betty, said that they all called him “captain.” He commented later to a daily newspaper, “This is silly. It’s just what you’d see in a grade B movie. The only person missing was Tallulah Bankhead.”

Then the storm hit.

In the lifeboats without motors, people bobbed in the cold water, hid under blankets and got seasick.

John Gyorkos was still wearing the tuxedo and dress shoes he had worn to festivities aboard the ship. Just before the rescue, he recalled, “I began to have doubts that we would all make it.”

Just before eight that Saturday morning, the Williamsburgh was on scene. It was the first large ship to arrive. Fertig pulled the tanker into position located more than 200 miles west of Sitka.

Pfister described the scene. The ship was “listing to the right and in danger of sinking. I saw passengers and crew bobbing in lifeboats in the storm.”

The tedious, 10-hour-long rescue began. The few boats with operating engines headed toward the Williamsburgh.

“[The sea] started splashing. And we couldn’t see the tanker nor the Prinsendam [even though it glowed with the blaze from below decks] for a long time, until the helicopter came,” David Levin said.

The weather got worse. One by one, the rescue helicopters would hover over a lifeboat, drop a sling or a basket, and hoist victims until they met their weight limit. They left the survivors on the Williamsburgh and returned to the lifeboats for more.

for more.

Passenger Lois Berk later wrote Coast Guard commandant, Admiral John Hayes, “It seemed like an impossible task. The wind was strong, the waves were very high. At first, there was no space on the lifeboat where the basket could be lowered, our boat was so crowded.”

“Somehow,” she went on, “after a few passes some people in the stern of our boat were able to make room and catch and firmly place the basket in the boat and one at a time, nine persons were raised to the helicopter, and flown to the tanker Williamsburgh.

“The ‘copter came back five times before I was lucky enough to be helped into the basket, hauled up, and quickly helped out of it, and taken to the tanker.

“I don’t know how many more trips were made by that copter, but I know not all the people were removed from lifeboat #3 [by that helicopter]. One copter ran out of fuel, one had an engine fail. I just wish I knew the number of the copter which rescued me and the names of its crew to express my tremendous gratitude for a job done beyond belief of ordinary service.

“I heard that the crewman who worked the basket was operating his first real rescue. I was among the first 45 he plucked from death.

“We were older people and stiff and frozen, many seasick and had to be lifted out of the basket. He must have had extraordinary strength,” she commented.

When the victims reached the Williamsburgh, they were taken below for coffee, hot drinks and warm conversation.

In the first hour, 150 people were airlifted to the deck of the Williamsburgh. At the end of that hour, the seas had reached 25-foot swells and the winds lashed the Gulf of Alaska at 50 knots.

The rescue continued. More people were plucked from the ocean and more and more became seasick and suffered from exposure. Those who were in poor condition were taken directly to Yakutat for treatment. From there, some were transported to Juneau or Sitka for further treatment.

Most of the survivors were in good health, glad to be alive. Several of them had to leave their medicines behind—for diabetes, heart problems and other ailments.

For hours, some lifeboats continued bobbing, waiting for the helicopter to appear from the storm. “When the seas started washing over the rail into the lifeboat, the cold was almost unbearable,” Gyorkos said.

Most people spent their waiting moments in prayer and song. Many of their small craft had run out of fuel making progress to the Williams¬burgh impossible, slowing rescue work. As boats with engines tried to tow those without, the lines snapped.

The Coast Guard Cutter Bo utwell arrived on scene and began taking on passengers in addition to Williamsburgh. The merchant ships Sohio, Intrepid, and Portland were also standing by to help.

utwell arrived on scene and began taking on passengers in addition to Williamsburgh. The merchant ships Sohio, Intrepid, and Portland were also standing by to help.

By noon, the seas had gotten worse and there were still more than 200 people to rescue. At least there were no casualties or serious injur¬ies yet.

Pfister reported the situation from the Williamsburgh four hours into the rescue, “We have very difficult sea conditions. We have 250 survivors board now but more are still in the water.”

The rescue operation continued, plucking one after another from a boat or a raft. The total num-ber on board Prinsendam was hard to deter¬mine. The sail list of passengers was accurate, and for the most part, the ship’s crew numbers were reliable, but several people were not listed at all. Among them were the entertainers and cruise staff, who managed to escape in a separate lifeboat. Luckily, their lifeboat had two Air Force paramedics aboard from the rescue operation. They had been dropped to the ship earlier to assist. Their boat was not found until 2 a.m., on Sunday, Oct. 5, when the paramedics caught a glimpse of the Cutter Boutwell, fired flare guns and were picked up by the cutter.

The seas were fighting success. By nightfall, Wabeke and his firefighters had given up. After they left the ship, flames engulfed the upper decks of the Prinsendam. The captain of the Dutch liner poetically was the last to leave the ship. When he reached safety, he looked skyward and saluted with hands clasped high above his head.

The final count was made: 360 passengers, 190 crew, 13 cruise staff and two paramedics. But just to be sure, the Coast Guard went to every lifeboat and raft for a double check, marking the craft with paint as they went. It was c onfirmed—all rescued, no life lost.

onfirmed—all rescued, no life lost.

The 1,100-foot Williamsburgh changed course and headed back to Valdez with more than 450 new faces crowded between its decks and into its passageways. The rest were aboard the Cutter Boutwell, on their way to Sitka.

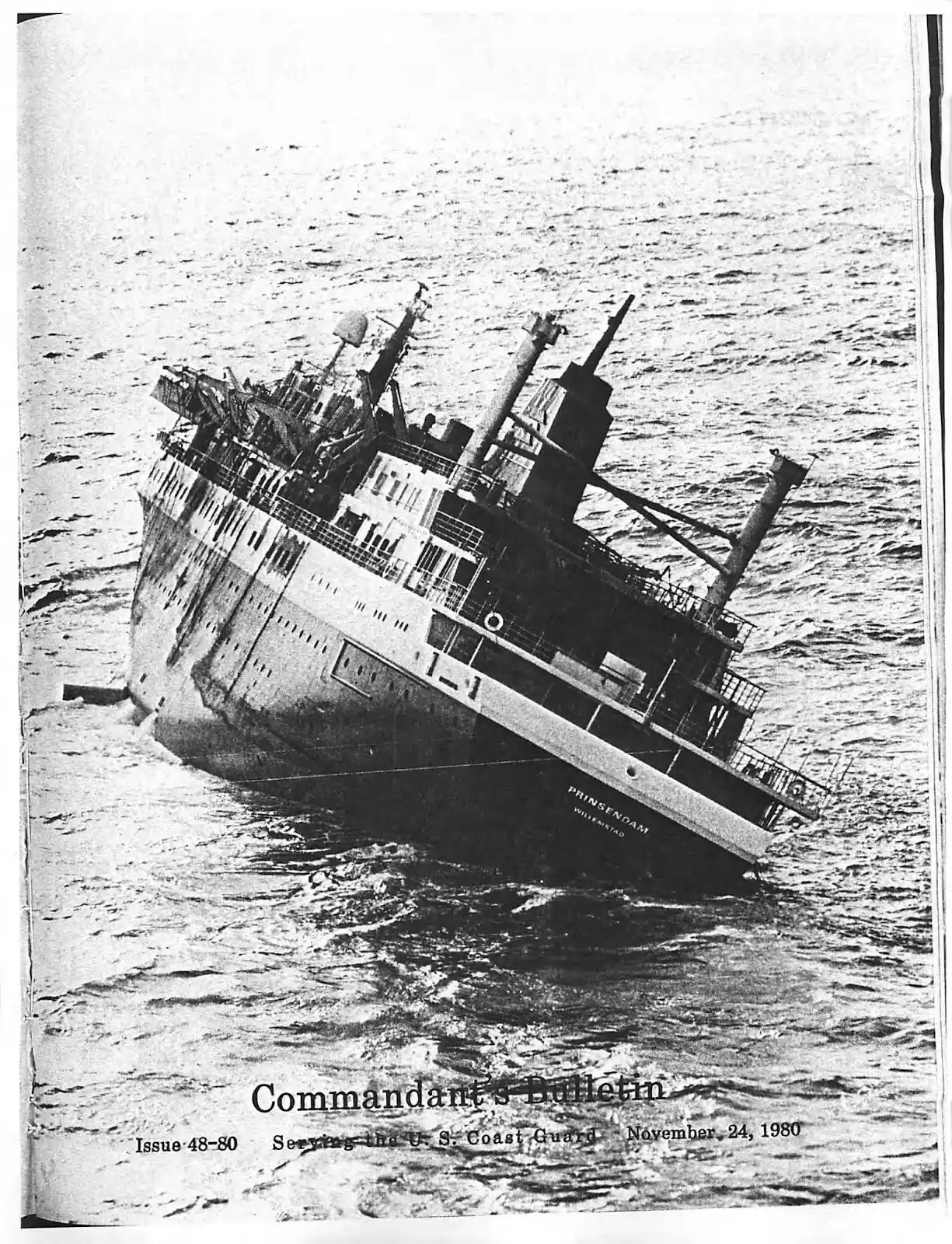

Located 360 miles east of Kodiak, the Prinsen¬dam listed, on fire.

Sunday began with more promising events. The survivors were on their way to shore and the weather had calmed considerably. A small damage control team from the Prinsendam’s crew returned to assess the damages. The major fire was out, but the main passageways still smoked and smoldered.

By Monday, the Canadian oceangoing tug Commodore Straits was en route to tow the 427-foot Dutch ship to Portland, Ore.

As time went on, the team continued to check the ship. The tow progressed slowly.

On Wednesday, Oct. 8, things changed for the worse. The fire reflashed about 5 a.m., and erupted when two portholes blew out. The fire spread through the ship, blowing out portholes and exploding what life rafts or boats remained.

Each day, the ship rode lo wer and lower in the water. By Oct. 10, A and B decks were submerged and the promenade deck was taking on water.

wer and lower in the water. By Oct. 10, A and B decks were submerged and the promenade deck was taking on water.

One week after the rescue began, the $25 million ship rolled on its side. Within three minutes, it sank. Though it carried 188,000 gallons of fuel and oil, the only remnants left behind were bits of debris and one life raft.

Since the ship ran into trouble outside U.S. territorial waters, investigation into the sinking was conducted by the ship’s flag country, the Ne¬therlands. The Coast Guard had a representative present to act as an interested observer.

In the aftermath, overflights were performed to check for oil that had escaped from the ship, which rests one mile below the surface.

One survivor wrote of the most vivid part of the week—first sight of the Coast Guard. “All I have heard for the last several days is how well the United States Coast Guard performed. Some may call the rescue effort a miracle, but it was only accomplished because of the experi¬ence and dedication of the Coast Guard,” wrote the president of Sears, Roebuck and Company, Ed Brennan. He continued, “Again, thank you very much personally. It’s an experience I shall treasure for the rest of my life.”

In a letter to Admiral Hayes, survivor Muriel Marvinney wrote:

“As a passenger on the ill-fated Prinsendam, I want to express my very deepest gratitude to the men of the Air-Sea Rescue squad who through their daring and devotion rescued me and my fellow passengers from a very certain fate. I want to congratulate you on your magnificent organization.”

Other letters poured in from commer¬cial organizations, federal agencies, well-wish¬ing citizens, members of Congress and senators, all praising the Coast Guard’s rescue efforts.

Most of the survivors said they intended to write their representative in Washington, D.C., praising the Coast Guard and asking for more money for Coast Guard operations.

Lois Berk knew it was more than just a helicopter crew that conducted the rescue. She wrote, “Another job done way beyond the ordi¬nary was the Coast Guardsman who answered the phone in Juneau from anxious relatives of the survivors.” Berk continued, “My daughter phoned him every two hours for about 36 hours. He was constantly courteous, well informed, generous with his information. Unfortunately, she didn’t get his name.”

Berk also wrote, “The purpose of this letter is to express my extreme gratitude to the many men who participated in this miraculous rescue—saving so many, with no serious injur¬ies. The greatest sea rescue in history.” And, she went on “It’s a great, heroic, exquisitely trained group, who can achieve such a record.” Later in her letter, she asked, “Could you express my gratitude to those men who participated?” She concluded, “And my congratulations to you for heading such an organization.”