The land turned to liquid. A long slice of the seaward edge of the plain…a section nearly a mile long and as much as six hundred feet wide-compacted, slumped, and then slid into the bay… men tumbled into the water, grasping for anything – timbers, boxes, debris-to stay afloat. One clung to the side of the fissure before he too, fell in. In the water, some of the victims were caught in a whirlpool of water and debris….It was as if the earth were swallowing everyone….

Henry Fountain, The Great Quake

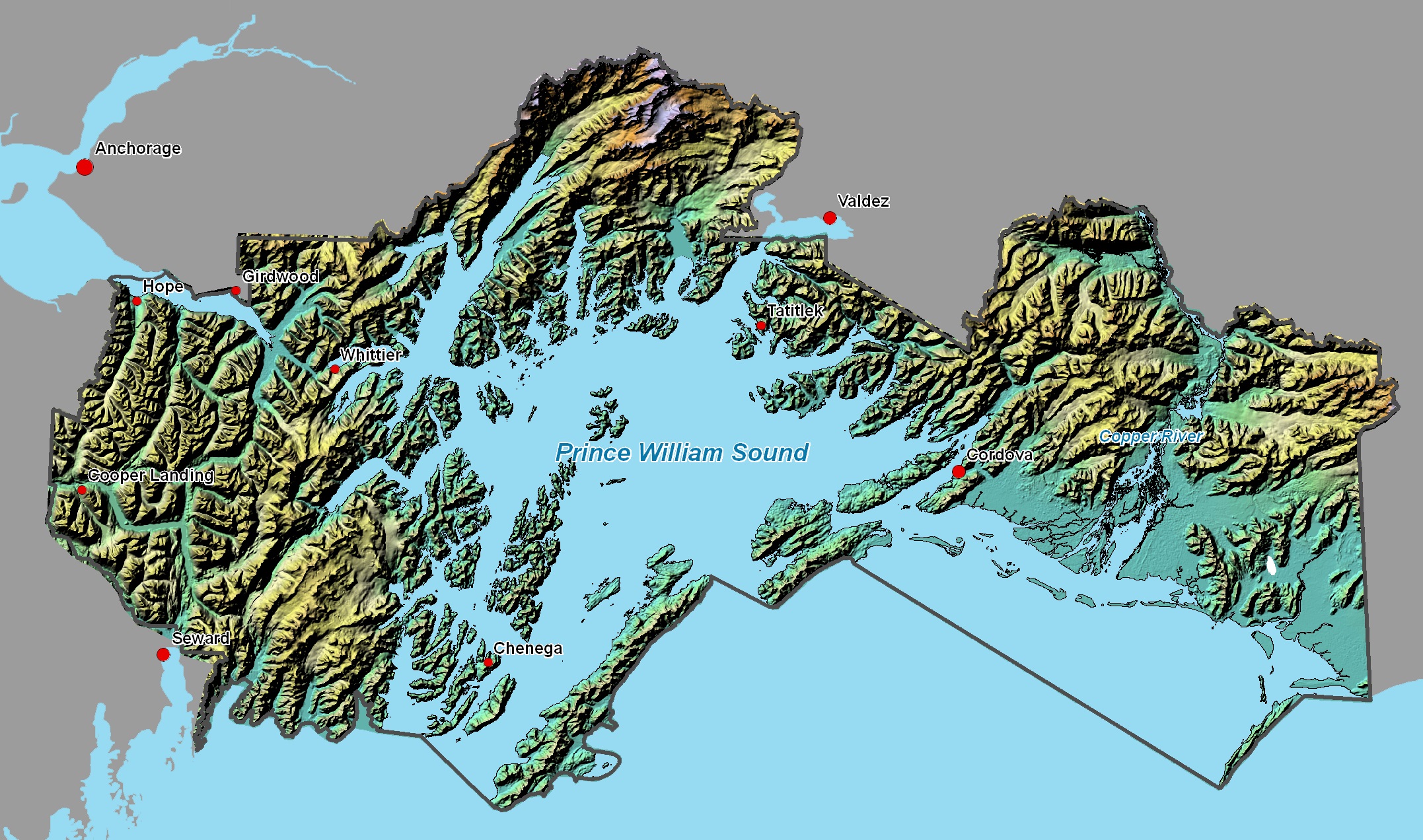

In his recent book, acclaimed writer Henry Fountain described the devastation that occurred March 27, 1964, at 5:36 p.m. Alaska Standard Time. That day, the strongest earthquake ever recorded in North America struck southern Alaska. Lasting almost five minutes, the megathrust quake, measuring 9.2 on the Richter scale, occurred when the Aleutian Fault ruptured near College Fjord in Prince William Sound 74 miles east of Anchorage. There, where the Pacific Plate subducts the North American Plate, 600 miles of fault line were torn asunder. The “Great Quake” caused soil liquefaction, ground fissures, structural collapses, tsunamis, and the death of 131 Alaskans.

In his recent book, acclaimed writer Henry Fountain described the devastation that occurred March 27, 1964, at 5:36 p.m. Alaska Standard Time. That day, the strongest earthquake ever recorded in North America struck southern Alaska. Lasting almost five minutes, the megathrust quake, measuring 9.2 on the Richter scale, occurred when the Aleutian Fault ruptured near College Fjord in Prince William Sound 74 miles east of Anchorage. There, where the Pacific Plate subducts the North American Plate, 600 miles of fault line were torn asunder. The “Great Quake” caused soil liquefaction, ground fissures, structural collapses, tsunamis, and the death of 131 Alaskans.

On that fateful day in Anchorage, the movement of the earth was gentle at first, a slight rumbling and rolling. Instead of subsiding, however, the movement grew violent. The earth heaved and fell as shockwaves rippled, accompanied by a deep roar. The waterfront in Valdez, located 119 miles east of Anchorage, was abuzz. One of the Alaska Steam Company’s converted Liberty ships was due to arrive on a regular cargo run from Seattle. The SS Chena had steamed into Valdez shortly after 4:00 p.m., under the command of Capt. Merrill Stewart. Carrying much-needed supplies, families gathered in anticipation. Since it was Good Friday, school was out. Children waited eagerly as crewmembers typically threw candy to kids on the dock and the ship’s cook handed out oranges and other fruits. Local men gathered on the pier, hired as dockworkers to unload the ship after it moored.

According to Valdez eyewit ness Gloria Day, the earth began to heave and ripple and buildings rose and fell. To her right, she saw the docked Chena’s stern rising at a sharp angle with its bow down and propellers exposed. Stewart was eating when he felt the impact of the quake. As he reached the bridge, he saw a swath of the city compact, slump, and slide into the bay. The docks, warehouses, and canneries of Valdez disappeared,

ness Gloria Day, the earth began to heave and ripple and buildings rose and fell. To her right, she saw the docked Chena’s stern rising at a sharp angle with its bow down and propellers exposed. Stewart was eating when he felt the impact of the quake. As he reached the bridge, he saw a swath of the city compact, slump, and slide into the bay. The docks, warehouses, and canneries of Valdez disappeared, sweeping away men, women, and children. Chena’s chief engineer saw men on shore running, only to be stopped by a huge fissure that opened and swallowed them. Those still alive were forced to slog their way through pools of mud and waste as the town’s sewer system erupted into geysers of filthy liquid.

sweeping away men, women, and children. Chena’s chief engineer saw men on shore running, only to be stopped by a huge fissure that opened and swallowed them. Those still alive were forced to slog their way through pools of mud and waste as the town’s sewer system erupted into geysers of filthy liquid.

What the heaving earth left untouched was leveled by the ensuing tsunami. A wave 200 feet high smashed into Shoup Bay near the Valdez inlet. The Union Oil Company tanks, situated on the waterfront, ruptured, igniting a massive fire. A submarine landslide caused a maelstrom in the harbor, sucking SS Chena down and slamming the ship repeatedly into the harbor bottom. The Chena survived the pummeling and radioed, “The town of Valdez, Alaska, just burst into flames. The whole dock is afire and the tanks at Union [Oil Company] and the other docks have started to burn.” Chena survived with the loss of three crewmembers—one of a heart attack and two killed by falling cargo. On shore, 28 residents died within minutes of the quake.

The situation in the native village of Chenega was just as disastrous. Located on a small island in Prince William Sound, in what has been described as “beautiful isolation,” Chenega was home to 68 people. The island was characterized by steep hills rising from the sea, studded with evergreen trees. Built on a hillside, the village itself was located on a small cove. A Russian Orthodox Church sat at the center of the village and a small schoolhouse at the top of a small hill.

Friday morning dawned cool and overcast at Chenega. In the schoolhouse, teacher Kris Madsen prepared for movie night and the feature was The House on Haunted Hill. She and a friend cleared away desks in the schoolhouse to make room for chairs and a screen, and then she went to fetch water from a nearby pond. When the earth started to shake, she looked toward the cove and saw the water recede and disappear, revealing a canyon more than 120 feet deep. The first wave arrived less than a minute into the quake. Two minutes later, a larger wave, 35 feet high, crashed into Chenega, leveling the village and nearly reaching the schoolhouse. When it receded, the waterfront, most of the homes, and the church were simply gone. Little was left except a field of debris that filled the cove and extended five miles into the sound. Those who survived, many injured and in shock, huddled together on the hilltop. Twenty-six people, including 13 children, more than one third of the village’s population, had died.

Friday morning dawned cool and overcast at Chenega. In the schoolhouse, teacher Kris Madsen prepared for movie night and the feature was The House on Haunted Hill. She and a friend cleared away desks in the schoolhouse to make room for chairs and a screen, and then she went to fetch water from a nearby pond. When the earth started to shake, she looked toward the cove and saw the water recede and disappear, revealing a canyon more than 120 feet deep. The first wave arrived less than a minute into the quake. Two minutes later, a larger wave, 35 feet high, crashed into Chenega, leveling the village and nearly reaching the schoolhouse. When it receded, the waterfront, most of the homes, and the church were simply gone. Little was left except a field of debris that filled the cove and extended five miles into the sound. Those who survived, many injured and in shock, huddled together on the hilltop. Twenty-six people, including 13 children, more than one third of the village’s population, had died.

In the town of Seward, spilled oil covered the water, caught fire, and was pushed ashore by the ensuing waves. One survivor said, “It was an eerie thing to see-a huge tide of fire washing ashore.” Radio traffic reported, “SS Alaska Standard reports the whole waterfront in Seward is afire and if a [Coast Guard]cutter is nearby, might be able to help.”

In fact, Coast Guard assets in the earthquake zone had taken considerable damage. LORAN Station Sitkinak reported, “LORAN out of operation. Repair time unknown, probably days at best. Water main and electrical cable broken. Five inch and more cracks in most walls. Deck settled three to six inches in some sections of station. Antenna still stands.” The station later reported, “Small tremors still occurring. No water pressure at station due to broken pipes….No electrical power in barracks….Two of three cisterns cracked…Transformer in transmitter building burned. Fire extinguished.”

cable broken. Five inch and more cracks in most walls. Deck settled three to six inches in some sections of station. Antenna still stands.” The station later reported, “Small tremors still occurring. No water pressure at station due to broken pipes….No electrical power in barracks….Two of three cisterns cracked…Transformer in transmitter building burned. Fire extinguished.”

Marking the entrance to Prince William Sound, the Coast Guard light station at Cape Hinchinbrook reported, “Had severe earth tremor. Evacuated building. Tremors can still be felt every 10 to 15 minutes. Loud noises can be heard…Now leaving station again. Will be back when shaking stops.” The station crew sent a second report: “Evacuated Station. There have been three waves hit this area.” They later reported, “Advise the district that we can’t stay in this building any longer. We are getting bad shakes every 10 or 15 minutes and the whole is land is shaking. We will be back as soon as it stops.” After evacuating the station, the Cape Hinchinbrook crew were exposed not just to the elements, but the threat of attack by wild brown bears that stalked the area. Cape Hinchinbrook next reported, “It sounds like the cliffs are falling on top of the island…There is an awful roar coming in from the sea now.”

land is shaking. We will be back as soon as it stops.” After evacuating the station, the Cape Hinchinbrook crew were exposed not just to the elements, but the threat of attack by wild brown bears that stalked the area. Cape Hinchinbrook next reported, “It sounds like the cliffs are falling on top of the island…There is an awful roar coming in from the sea now.”

Despite the confusion caused by the unfolding disaster, radio traffic reported that the Coast Guard response was underway: “[Coast Guard Cutter] Sedge en route to Valdez. [Coast Guard Cuter] Bittersweet en route to Seward. [Coast Guard Cutter] Storis and [Coast Guard Cutter] Sorrel proceeding toward Prince William Sound. [CGC] Minnetonka remaining Cape Sarichef area. Urgent broadcast for all vessels proceeding nearest villages and assist and report.”

In a 2007 interview, Coast  Guard Lt. Peter Corson recounted, “I was in my house in Cordova eating dinner when the quake struck. Our house came almost completely off the foundation. I ran down to the dock. It had split in half and was heaving back and forth. We had to wait until the gap closed before jumping across

Guard Lt. Peter Corson recounted, “I was in my house in Cordova eating dinner when the quake struck. Our house came almost completely off the foundation. I ran down to the dock. It had split in half and was heaving back and forth. We had to wait until the gap closed before jumping across it to get to [Coast Guard Cutter] Sedge.”

it to get to [Coast Guard Cutter] Sedge.”

According to Corson, the Sedge, a buoy tender was at “charlie condition,” with engines down for maintenance. Ordered to Valdez, the crew scrambled to get underway. While transiting Cordova’s 60-foot-deep shipping channel, the water level dropped and Sedge came to rest on the channel bottom. Sedge reported, “We are aground in the middle of Kodiak Channel.” Ten minutes later, water rushed back into the channel refloating Sedge, which then continued on to Valdez, reporting, “We are afloat and underway to Valdez. No apparent damage.” Before long, Sedge witnessed the devastation at Chenega and radioed, “Town of Chenega destroyed. Half of population missing. They require assistance badly.”

At about the same time Sedge got hit, one of its crewmembers, Petty Officer Third Class Frank Reed, was on leave photographing wildlife on the south end of nearby Kayak Island. Falling rocks left hi m with a broken leg. Three of his shipmates tried to save him, but were hit by a tidal wave. Coast Guard District Seventeen was later notified of Reed’s case. “Tidal wave hit his unit. Reed, Frank O. EN3 killed during wave. Drowned and washed out to sea.” Reed’s body was never found.

m with a broken leg. Three of his shipmates tried to save him, but were hit by a tidal wave. Coast Guard District Seventeen was later notified of Reed’s case. “Tidal wave hit his unit. Reed, Frank O. EN3 killed during wave. Drowned and washed out to sea.” Reed’s body was never found.

At Kodiak, the earthquake did not spare the Coast Guard air detachment (AIRDET). One of the maintenance crew recalled water rushing repeatedly into the hangar as the crews scrambled to evacuate the aircraft. A C-123 aircraft suffered salt-water emersion to the level of its floorboards, but all the aircraft were eventually moved to safety and deemed operational.

Three of the AIRDET’s HU-16 Albatrosses successfully departed to survey damage on Kodiak Island, and the east coast of the Kenai Peninsula up to Cordova and Cook Inlet. Coast Guard CG-1271 reported severe damage in Seward: “Estimated 50 houses destroyed. All dock area destroyed. All railway yard damaged. Oil tank still burning. No communications.” Strangely enough, the pilot reported only three damaged buildings in Chenega. Perhaps he was unfamiliar with Chenega and saw the wide swath of new beach, unaware that much of the village was gone.

Back at AIRDET Kodiak, the hangar was deemed unsafe and all the tools and equipment unserviceable. It was reported, “No estimate can be made of return to normal operations. Expect at least several weeks. Believe can maintain capability required to handle present emergency.” In fact, Coast Guard aircraft had been actively surveying damage, and HU-16 CG-5848 successfully evacuated stranded personnel from outlying areas. Coast Guard aircraft also located seven bodies floating in Kalsin Bay.

Later, the Sedge reported 1,0 00 Valdez residents were evacuating by land. “Erratic tides grounded Sedge power boat. Undamaged. Slight tremors are still felt. SS Chena and Sedge standing by to determine success of evacuation attempt.” Alaska-based U.S. Army units arrived and determined that land evacuation could be completed without the ships’ assistance. Coast Guard Cutter Sorrel later reported it was proceeding to Chenega to survey damage and render whatever assistance possible.

00 Valdez residents were evacuating by land. “Erratic tides grounded Sedge power boat. Undamaged. Slight tremors are still felt. SS Chena and Sedge standing by to determine success of evacuation attempt.” Alaska-based U.S. Army units arrived and determined that land evacuation could be completed without the ships’ assistance. Coast Guard Cutter Sorrel later reported it was proceeding to Chenega to survey damage and render whatever assistance possible.

Those stationed at Cape Hinchinbrook Light Station were still on edge. “Tremors still felt every [two to three] minutes and also loud noises from all parts of the island. Request advise if these tremors are felt in other areas. It sounds and feels like the island is trying to push up in the middle.” After two days of repeated tremors, Cape Hinchinbrook received the following message from District Seventeen commander, Rear Admiral George Synon:

- I am fully aware of the hard and perilous situation now being faced by you and your crew. I am proud of the courage you have shown thus far and of the efforts you have made to keep essential equipment operating.

- Please inform all hands that I am confidant under your leadership they will continue to display the bravery and devotion to duty, which are always the mark of Coast Guardsmen in the face of danger.

Despite the admiral’s words of encouragement, the situation at Cape Hinchinbrook deteriorated. Due to several tremors in one hour, station personnel decided to evacuate to a hill behind the installation. They reported, “Will check on radio periodically. Equipment will be left operating and also checked periodically.” Coast Guard Cutter Sedge received orders to evacuate Cape Hinchinbrook’s personnel. Orders were given to “Shut down all equipment and secure building and material just prior to departure providing crew is not endangered while doing so.”

On March 28th, the day of the quake, President Lyndon Johnson declared Alaska a disaster area. The days following the earthquake were described as a “blur,” punctuated by moments of fear and scenes of chaos and devastation. Despite damage to a number of Coast Guard installations, Coast Guard members worked through the chaos, kept their units as operational as possible and offered assistance where needed. Their experiences serve as another example of the Coast Guard motto Semper Paratus, “Always Ready.”