World War II officially began in December 1941 at Pearl Harbor, where Coast Guard cutters put up anti-aircraft barrages against Japanese aircraft and performed harbor and anti-submarine patrols alongside U.S. Navy assets. However, it was in 1942 that the Coast Guard experienced many of its history-making events of the war.

World War II officially began in December 1941 at Pearl Harbor, where Coast Guard cutters put up anti-aircraft barrages against Japanese aircraft and performed harbor and anti-submarine patrols alongside U.S. Navy assets. However, it was in 1942 that the Coast Guard experienced many of its history-making events of the war.

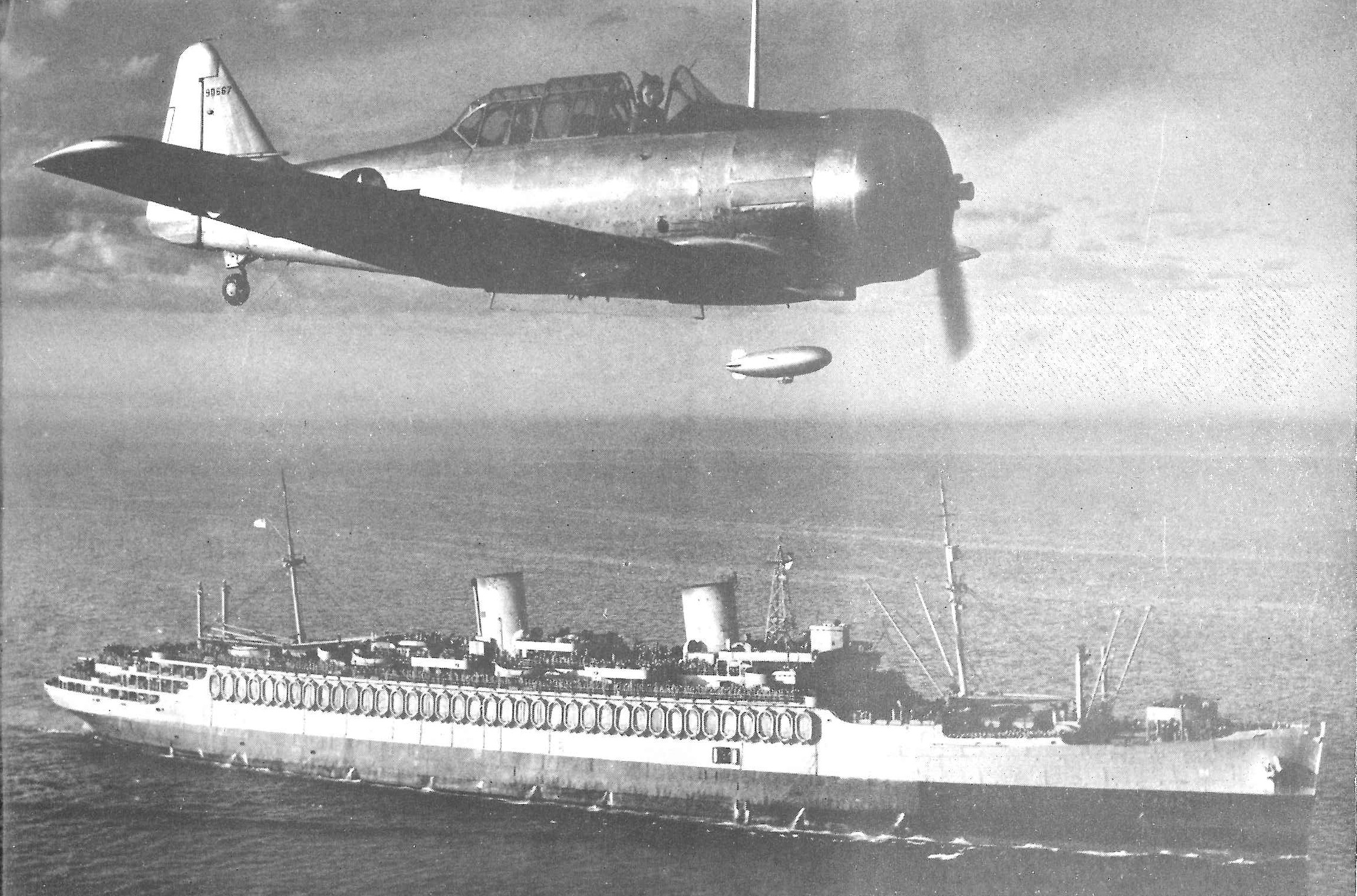

Early in 1942, the Coast Guard suffered its first wartime combat casualties when enemy forces attacked two Coast Guard-manned vessels serving on opposite sides of the world. Off the coast of Iceland, U-132 attacked the Secretary-Class Cutter Alexander Hamilton, which suffered 26 killed and 56 wounded. It capsized and had to be sunk by friendly fire on Jan. 30, 1942. Hamilton was the first American warship lost to enemy action after the U.S. declared war. That same day, the Coast Guard-manned transport USS Wakefield was refueling in besieged Singapore when a Japanese bomb from a high-level air raid penetrated the ship killing four Coast Guardsmen. Despite the casualties, Wakefield survived the bombing and successfully delivered its cargo of civilian refugees to India.

By February, President Franklin Roosevelt transferred the Bureau of Marine Inspection and Navigation to the Coast Guard. Already responsible for merchant-marine personnel and ship safety, this added mission gave the Coast Guard oversight of merchant vessel safety from the drawing board to the scrap yard. During the war, marine safety developed into such an important service mission that it remained permanently within the Coast Guard after the war.

Naval historians generally ov erlook the Coast Guard’s participation in the Battle of the Atlantic. The Coast Guard’s fleet of medium-and high-endurance cutters, and numerous Coast Guard-manned destroyer escorts and patrol frigates, served a vital role as convoy escorts. All of these warships helped protect Allied convoys ensuring the timely and

erlook the Coast Guard’s participation in the Battle of the Atlantic. The Coast Guard’s fleet of medium-and high-endurance cutters, and numerous Coast Guard-manned destroyer escorts and patrol frigates, served a vital role as convoy escorts. All of these warships helped protect Allied convoys ensuring the timely and safe arrival of personnel, food and military cargoes to Europe. Besides escort duty in the North Atlantic, Coast Guard vessels escorted convoys across the central Atlantic, in the Mediterranean and Caribbean, and along America’s shores. In May 1942, the escort cutter Icarus sank U-352 off the North Carolina coast capturing the first German prisoners of war (POW) by U.S. forces. Over the course of the war, Coast Guard-manned warships sank 11 U-boats.

safe arrival of personnel, food and military cargoes to Europe. Besides escort duty in the North Atlantic, Coast Guard vessels escorted convoys across the central Atlantic, in the Mediterranean and Caribbean, and along America’s shores. In May 1942, the escort cutter Icarus sank U-352 off the North Carolina coast capturing the first German prisoners of war (POW) by U.S. forces. Over the course of the war, Coast Guard-manned warships sank 11 U-boats.

Like previous conflicts, World War II altered the service’s ethnic make-up and advanced the role of minorities. The first 150 African Americans had volunteered for the Coast Guard in March 1942 and received training at the service’s desegregated facility at Manhattan Beach, N.Y. By May, all Coast Guard ratings were opened to minorities. Some of these African Americans received shore duty manning all-black Coast Guard stations, such as ones at Pea Island, N.C., and Tiana Beach, N.Y.

During the war, the Coast Guard led in the development of certain military technologies. LORAN is the military acronym for long-range navigation, which used radio waves to help planes and ships determine their exact location in any weather conditions. In March 1942, the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the Coast Guard to design, construct, and operate a chain of these LORAN transmitting stations. The Coast Guard built 49 LORAN stations stretching from Greenland to the Pacific to assist military aircraft and ships conducting combat operations. Though built to support the war effort, the system was adapted for civilian use and the Coast Guard continued to operate LORAN stations until the satellite-based Global Positioning System (or GPS) made them obsolete in the 21st century.

In May, the Chief of Naval Operations requested the Coast Guard Reserve to organize a coastal patrol. Often referred to as the “Hooligan Navy” or “Corsair Fleet,” the Coastal Picket Patrol’s mission was to supplement coastal naval forces employed in anti-submarine and rescue duties. Made up of privately owned yachts equipped with machine guns, a few depth charges and a radio, the yachts were supposed to attack enemy submarines whenever possible. Yacht owners usually remained in command of their boats with a temporary enlisted rank of chief

charges and a radio, the yachts were supposed to attack enemy submarines whenever possible. Yacht owners usually remained in command of their boats with a temporary enlisted rank of chief  boatswain’s mate. At first, Corsair Fleet crews were made up of college boys, Boy Scouts, beachcombers and ex-rumrunners. Almost anyone who could reef a sail and steer a course, and many who could not, qualified as crewmembers. Later in the war, Corsair Fleet crews comprised better trained and more experienced seamen.

boatswain’s mate. At first, Corsair Fleet crews were made up of college boys, Boy Scouts, beachcombers and ex-rumrunners. Almost anyone who could reef a sail and steer a course, and many who could not, qualified as crewmembers. Later in the war, Corsair Fleet crews comprised better trained and more experienced seamen.

In June, U-boat attacks had reached their wartime high and U.S. strategists decided the development of a new technology called the “helicopter” might help combat the underwater menace. Due in large part to the insistence of Commandant Russell Waesche, the Chief of Naval Operations placed responsibility for helicopter development with the Coast Guard. Coast Guard Capt. Frank Erickson joined aircraft designer Igor Sikorsky at New York’s Floyd Bennett Airfield to develop the helicopter into a revolutionary aviation technology. The helicopter proved invaluable to the U.S. military, and rotary-wing aircraft have since become a staple of military and civilian aviation throughout the world.

Meanwhile, U-boats supporting the Nazi’s Operation “Pastorious” landed two sabotage teams on the East Coast, one in Florida and the other on Long Island. The mission of each team of four me n was to strike key U.S. factories and railroads. On a foggy evening in June, Coast Guardsman John Cullen witnessed the first German team shortly after it landed on Long Island. Within weeks, the Federal Bureau of Investigation apprehended all the enemy agents in New York and Florida. All but two of the saboteurs were hanged ending this failed Nazi sabotage attempt.

n was to strike key U.S. factories and railroads. On a foggy evening in June, Coast Guardsman John Cullen witnessed the first German team shortly after it landed on Long Island. Within weeks, the Federal Bureau of Investigation apprehended all the enemy agents in New York and Florida. All but two of the saboteurs were hanged ending this failed Nazi sabotage attempt.

The Coast Guard’s search and rescue mission required the service to save the lives of all victims of the naval war. Coast Guard lifeboats brought in scores of survivors from tankers and ca rgo vessels torpedoed along the East Coast and the service’s amphibian aircraft guided surface ships to survivors along the coasts or landed on the open ocean to perform water rescues. Overall, Coast Guard cutters and aircraft rescued nearly 1,000 Allied and Axis survivors along the North Atlantic convoy routes, 1,600 along the American coast and 200 in the Mediterranean, thereby continuing one of the Coast Guard’s core missions.

rgo vessels torpedoed along the East Coast and the service’s amphibian aircraft guided surface ships to survivors along the coasts or landed on the open ocean to perform water rescues. Overall, Coast Guard cutters and aircraft rescued nearly 1,000 Allied and Axis survivors along the North Atlantic convoy routes, 1,600 along the American coast and 200 in the Mediterranean, thereby continuing one of the Coast Guard’s core missions.

More history making events happened in the summer. In August, the Coast Guard’s first major offensive took place in the South Pacific, at Guadalcanal. There, Coast Guard-manned ships and boats ensured the steady flow of fresh troops, supplies, and equipment to marines on the front lines. Moreov er, when the Marines needed smallboats for reconnaissance and combat missions, Coast Guard crews were always ready to operate them. Assigned to Guadalcanal, Signalman Douglas Munro, the only Coast Guard member awarded the Medal of Honor, received it posthumously for performing a mission common to the Coast Guard—rescuing those who go in harm’s way. In this case, Munro’s flotilla of landing craft evacuated a marine battalion ambushed by the Japanese at Point Cruz, Guadalcanal.

er, when the Marines needed smallboats for reconnaissance and combat missions, Coast Guard crews were always ready to operate them. Assigned to Guadalcanal, Signalman Douglas Munro, the only Coast Guard member awarded the Medal of Honor, received it posthumously for performing a mission common to the Coast Guard—rescuing those who go in harm’s way. In this case, Munro’s flotilla of landing craft evacuated a marine battalion ambushed by the Japanese at Point Cruz, Guadalcanal.

The Coast Guard also participat ed in all of the Allied amphibious landings in North Africa and Italy, beginning with the November 1942 Operation “Torch” landings in French-held North Africa. The service’s extensive record of lifesaving, smallboat handling and shallow water operations made Coast Guardsmen the U.S. military’s foremost experts in amphibious operations.

ed in all of the Allied amphibious landings in North Africa and Italy, beginning with the November 1942 Operation “Torch” landings in French-held North Africa. The service’s extensive record of lifesaving, smallboat handling and shallow water operations made Coast Guardsmen the U.S. military’s foremost experts in amphibious operations.

The war also advanced the role of women. Late in November 1942, Congress approved legislation creating the Coast Guard Women’s Reserve. This female reserve corps adopted the term SPAR, an acronym for the Coast Guard motto, Semper Paratus—Always Ready. The establishment of the SPARs showed legislative recognition of the duty and right of American women to serve in the U.S. armed services. Between 1942 and 1946, nearly 12,000 women volunteered to serve as SPARs. This number included the service’s first minority women to become Coast Guard officers and enlisted personnel.

In 1942, the Coast Guard proved itself Semper Paratus, or “Always Ready,” to perform any maritime missions required by the war effort. That year saw a rapid influx of assets and personnel; formation of the Coast Guard Reserve; racial desegregation of the service; development and implementation of new technologies, such as LORAN and the helicopter; addition of the former Bureau of Marine Safety and Navigation; introduction of active-duty women to officer ranks and enlisted ratings previously held by men; and many more historic firsts and events!