I swam the line ashore while machine gun bullets were dropping around like rain. . . thirty-six soldiers came over the side. They started pulling themselves toward the shore through the withering fire. Only six made it.

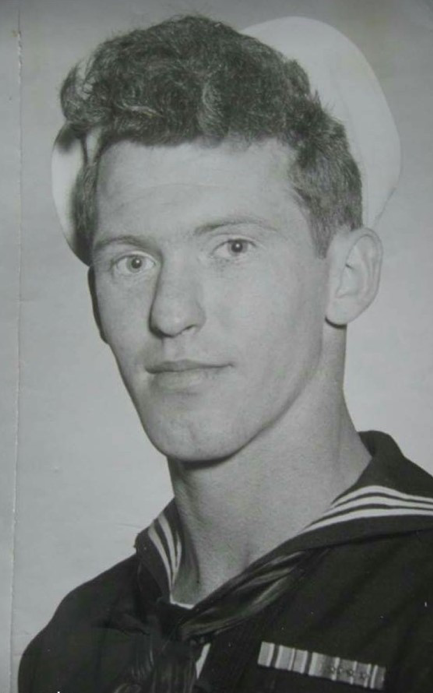

Seaman 1st Class Eugene Oxley, U.S. Coast Guard reserve

On July 17, 1942, at the age of 18, Eugene Edwin Oxley, enlisted in the United States Coast Guard. Two years later, he would distinguish himself on D-Day, earn the nickname “Lucky Ox,” and receive the Silver Star Medal for combat heroism.

On July 17, 1942, at the age of 18, Eugene Edwin Oxley, enlisted in the United States Coast Guard. Two years later, he would distinguish himself on D-Day, earn the nickname “Lucky Ox,” and receive the Silver Star Medal for combat heroism.

Hailing from the small burg of Stilesville, Indiana, Oxley joined the legions of young men who enlisted in the Coast Guard. After he signed recruitment papers at Indianapolis, the Coast Guard sent him to St. Louis where he formally enlisted and shipped out to the Coast Guard’s Recruit Training Center at Curtis Bay, Maryland.

After boot camp, Oxley was assigned to the Coast Guard-manned LCI-85. LCI-85 was part of an unusual class of vessels designed for one purpose: landing large numbers of troops on enemy shores. The British developed the unusual looking landing craft--some crediting its genesis to Winston Churchill--that would ultimately be designated the “LCI(L)” also known as Landing Craft, Infantry. Lovingly called “Lousy Civilian Idea” by their crews, LCIs could reach a top speed of 17 knots, but their narrow hull and shallow draft made them anything but comfortable at sea.

Typically, an LCI approached its landing area and dropped a stern anchor as it prepared to beach itself. After beaching, two long ramps placed on either side of the LCI’s bow were run out and a crewmember deployed down each ramp. The crewmen ran ashore carrying a line with a 30-pound anchor at the end secured to the ramp on the other end. These brave volunteers placed the anchor in the sand to keep the line taught and guide the disembarking troops ashore.

Among the hundreds of LCIs constructed in shipyards across the U.S., was a flotilla crewed entirely by Coast Guardsmen designated Flotilla 10. This LCI flotilla served in battle against Axis forces in the assaults on Sicily and mainland Italy. For D-Day, Flotilla 10 was reinforced with 12 Navy-manned LCIs, increasing the flotilla’s total number to 36 landing craft divided equally between ones destined for the infamous Omaha and Utah beaches.

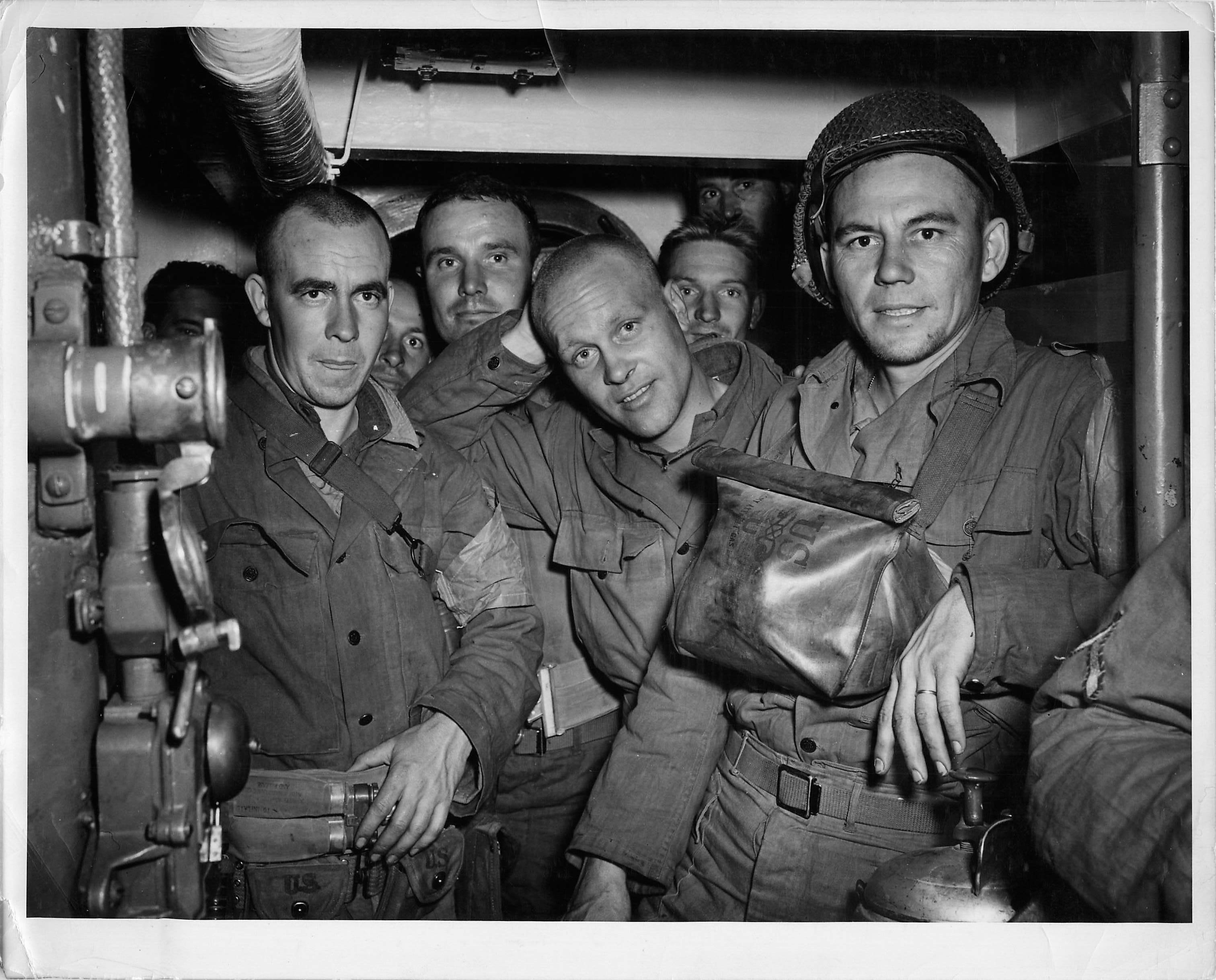

As late May 1944 approached, troops were placed aboard the LCIs and no one permitted ashore. With over 200 soldiers and 30 crewmen aboard each LCI, one can imagine the claustrophobia experienced in the cramped quarters. After foul weather postponed the landings scheduled for June 5th, word spread that they would take place the morning of the 6th. The 85 was scheduled to land on the right side of the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach at 8:30 a.m., two hours after the first landings. Oxley volunteered to take a ramp line ashore once his ship grounded on the beach.

As late May 1944 approached, troops were placed aboard the LCIs and no one permitted ashore. With over 200 soldiers and 30 crewmen aboard each LCI, one can imagine the claustrophobia experienced in the cramped quarters. After foul weather postponed the landings scheduled for June 5th, word spread that they would take place the morning of the 6th. The 85 was scheduled to land on the right side of the Easy Red sector of Omaha Beach at 8:30 a.m., two hours after the first landings. Oxley volunteered to take a ramp line ashore once his ship grounded on the beach.

As with most combat situations, LCI-85’s landing did not go according to plan. Waiting in the hills above Omaha Beach were well-armed Nazi defenders, concealed in bunkers and reinforced trenches. Unfortunately for the American troops, Allied bombers supposed to soften up the defenses had dropped their payloads well inland of the Germans. They also missed thousands of deadly “Rommel’s Asparagus,” nicknamed after German general Irwin Rommel and made of small wooden logs, which covered the Normandy beaches from the high-tide line to well below the low-tide line. Atop many of these stakes were Teller mines set to detonate as soon as watercraft touched them.

Early that morning, Flotilla 10’s LCIs approached the French coast in the dark. They gathered together ten miles offshore and began circling to await instructions from control vessels directing incoming ships. At 8:20 a.m., the LCIs fanned out and approached the Line of Departure, an artificial starting line on their charts that paralleled the beach. The control vessel then directed the 85 by loud hailer to head in. What no one noticed was a strong current that pushed the LCIs away from their designated beaches, so the 85 no longer steamed to its designated landing area.

As it approached the beach, the 85 let go its stern anchor as it prepared to ground and let out its infantry ramps. Next, Oxley ran down the portside ramp, with his line and anchor, and jumped into the water. But the 85 had not grounded on the beach, but on a shallow obstacle, so Oxley plunged in over his head while the LCI remained too far out to disembar k troops. Oxley’s shipmates pulled him back in and the 85 backed off. By this time, the stern anchor winch had failed and there were no smaller landing craft to convey troops to the beach, so the 85 attempted another landing. As the LCI backed off the beach, a large enemy shell hit one of its troop compartments—the grim sounds of wounded and dying Army troops were amplified to the rest of the ship by 85’s voice tubes.

k troops. Oxley’s shipmates pulled him back in and the 85 backed off. By this time, the stern anchor winch had failed and there were no smaller landing craft to convey troops to the beach, so the 85 attempted another landing. As the LCI backed off the beach, a large enemy shell hit one of its troop compartments—the grim sounds of wounded and dying Army troops were amplified to the rest of the ship by 85’s voice tubes.

The 85’s captain located a clear stretch of beach about 100 yards away and ordered the 85 forward. It grounded once again, but this time over a “Rommel’s Asparagus” topped by a mine that blew a hole in the ship’s forward compartment. Heavy enemy machinegun fire began peppering the vessel on the starboard side so only the port ramp was operational. Once again, Oxley grabbed the line, jumped overboard and made it to shore. In the process, the anchor he was supposed to secure in the sand had been shot away. Undeterred, he braced himself on the beach under heavy fire and held the line taut for the debarking troops. For the soldiers, it was a march into oblivion with only six out of the 36 men surviving the withering fire to set foot on the beach. Miraculously, Oxley was never hit.

The 85’s captain located a clear stretch of beach about 100 yards away and ordered the 85 forward. It grounded once again, but this time over a “Rommel’s Asparagus” topped by a mine that blew a hole in the ship’s forward compartment. Heavy enemy machinegun fire began peppering the vessel on the starboard side so only the port ramp was operational. Once again, Oxley grabbed the line, jumped overboard and made it to shore. In the process, the anchor he was supposed to secure in the sand had been shot away. Undeterred, he braced himself on the beach under heavy fire and held the line taut for the debarking troops. For the soldiers, it was a march into oblivion with only six out of the 36 men surviving the withering fire to set foot on the beach. Miraculously, Oxley was never hit.

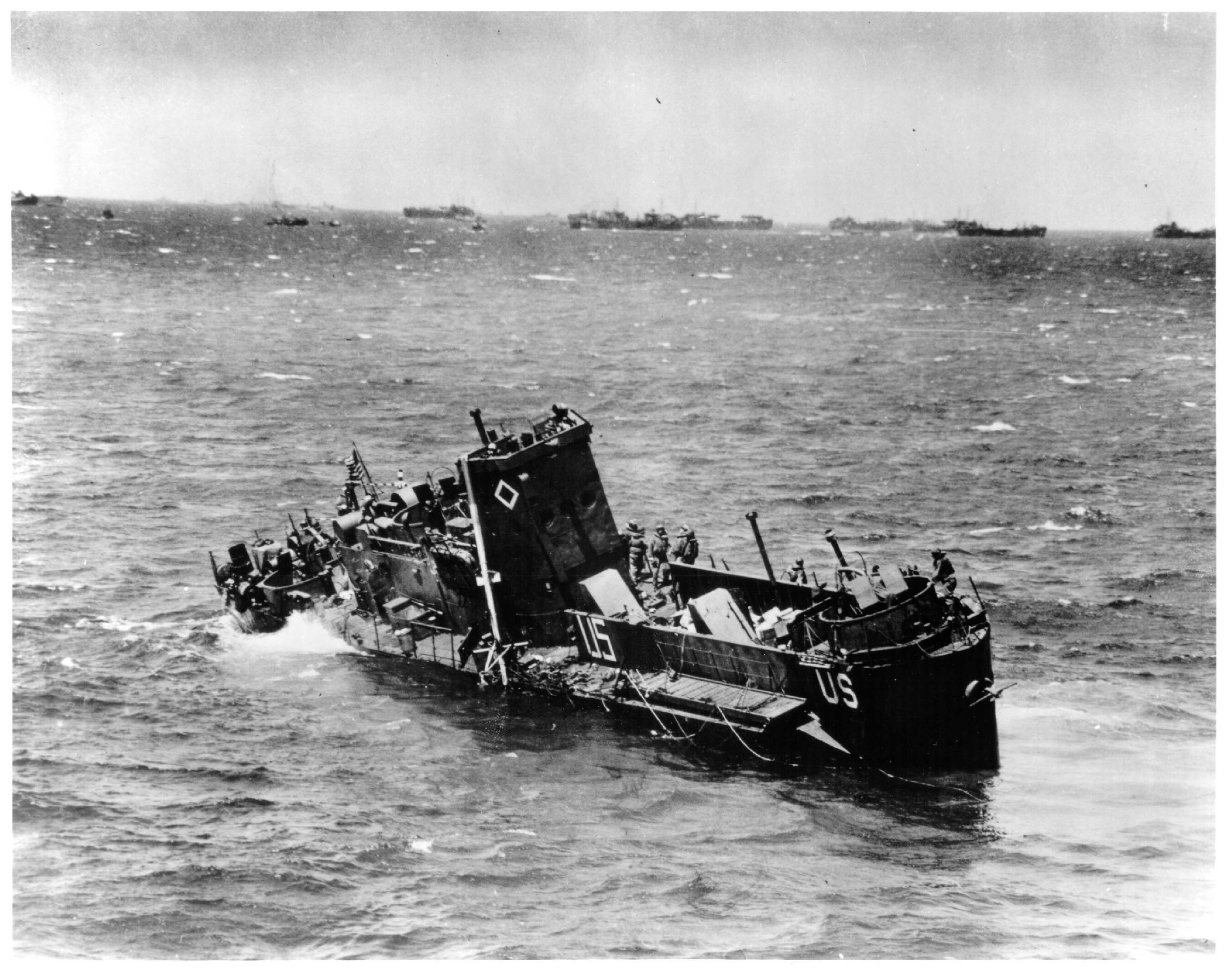

Meanwhile, incoming shellfire was devastating, with hits taking their toll on the 85’s crew and soldiers in the troop compartments. After a shell hit the port ramp and blew it off the LCI, the ship backed away once again, leaving Oxley stranded on the beach. The 85 later managed to offload the remaining troops into small landing craft, which took the men ashore while the 85 made it out to an area where the troopships gathered. There, it unloaded the dead and wounded to the Coast Guard-manned transport USS Samuel Chase. In all, the thin-skinned 85 suffered six direct hits from German artillery with dozens of troops killed, but miraculously only four Coast Guardsmen were wounded. Despite the crew’s efforts to save their ship, the 85 capsized and sank after unloading its dead and wounded men.

Oxley was left to his own devices on Omaha Beach. By now, he was shoeless with no battle helmet, so he dug a small foxhole and hunkered down. Unfortunately, Lucky Ox had to hide not only from the enemy, but also Mother Nature as the tide began to rise up the beach. As soon as he was flooded out of one foxhole, he dug another. In the span of an hour, he dug and was then flooded out of half a dozen soggy holes.

Oxley was left to his own devices on Omaha Beach. By now, he was shoeless with no battle helmet, so he dug a small foxhole and hunkered down. Unfortunately, Lucky Ox had to hide not only from the enemy, but also Mother Nature as the tide began to rise up the beach. As soon as he was flooded out of one foxhole, he dug another. In the span of an hour, he dug and was then flooded out of half a dozen soggy holes.

Soon, he saw a smaller LCT preparing to return to sea after delivering its troops. He sprinted for it and got aboard. But misfortune struck a second time and, as the craft backed off the beach, it too sustained multiple shell hits and began to sink. Oxley abandoned it and again found himself in the water. He swam to the nearby LCI-93, another Coast Guard-manned LCI, which had just finished debarking its first load of troops.

LCI-93 steamed back to the troop transport staging area to collect m ore troops and headed back to the beaches. Unfortunately, when it landed, the 93 was also targeted by German artillery, sustained mass casualties and had to be abandoned. Oxley jumped off its stern as he had with the LCT. He later noted that he felt like a jinx. Once again, he swam ashore, later telling a reporter “I lay there in a foxhole from 3 p.m. to 5:45 p.m. It was hell!” After nearly three hours hiding from enemy machinegun fire in a shallow foxhole, Oxley was evacuated to a destroyer by landing craft. Having endured 12 hours of unrelenting enemy artillery and machinegun fire, Oxley only had his trouser bottoms shot away, but no wounds.

ore troops and headed back to the beaches. Unfortunately, when it landed, the 93 was also targeted by German artillery, sustained mass casualties and had to be abandoned. Oxley jumped off its stern as he had with the LCT. He later noted that he felt like a jinx. Once again, he swam ashore, later telling a reporter “I lay there in a foxhole from 3 p.m. to 5:45 p.m. It was hell!” After nearly three hours hiding from enemy machinegun fire in a shallow foxhole, Oxley was evacuated to a destroyer by landing craft. Having endured 12 hours of unrelenting enemy artillery and machinegun fire, Oxley only had his trouser bottoms shot away, but no wounds.

Eugene Oxley and other Coast Guardsmen who lost their vessels that day, including four of Flotilla 10’s LCIs, returned to England where they were placed in “survivor camps” until reassigned to new units or sent home. Awarded the Silver Star Medal for his incredible actions on D-Day, Oxley was sent home a war hero. In the U.S., he participated in Coast Guard public relations events, including War Bond tours and recruitment drives. The head of Coast Guard Public Relations Division at the time, Rear Admiral Ellis Reed-Hill, would later note that “of all the Coast Guard heroes during the Normandy landings, Oxley stands out as one the Service may be justly proud!”

Over 75 years ago, Coast Guardsmen like Eugene Oxley participated in the largest amphibious operation the world had ever seen. Later known as D-Day, the Allied landings on the Normandy Coast of France would become one of the defining moments in Western History. That operation, which carried the code name of “Overlord,” with the naval component referred to as “Neptune,” led to the defeat of Nazi Germany and end of the Second World War in Europe.