Lt. Brown and the gallant volunteers set an example worthy of the highest traditions of any Service or any Nation.

Rear Adm. Heathcoat Grant, senior Royal Navy officer, Base Gibraltar, 1918

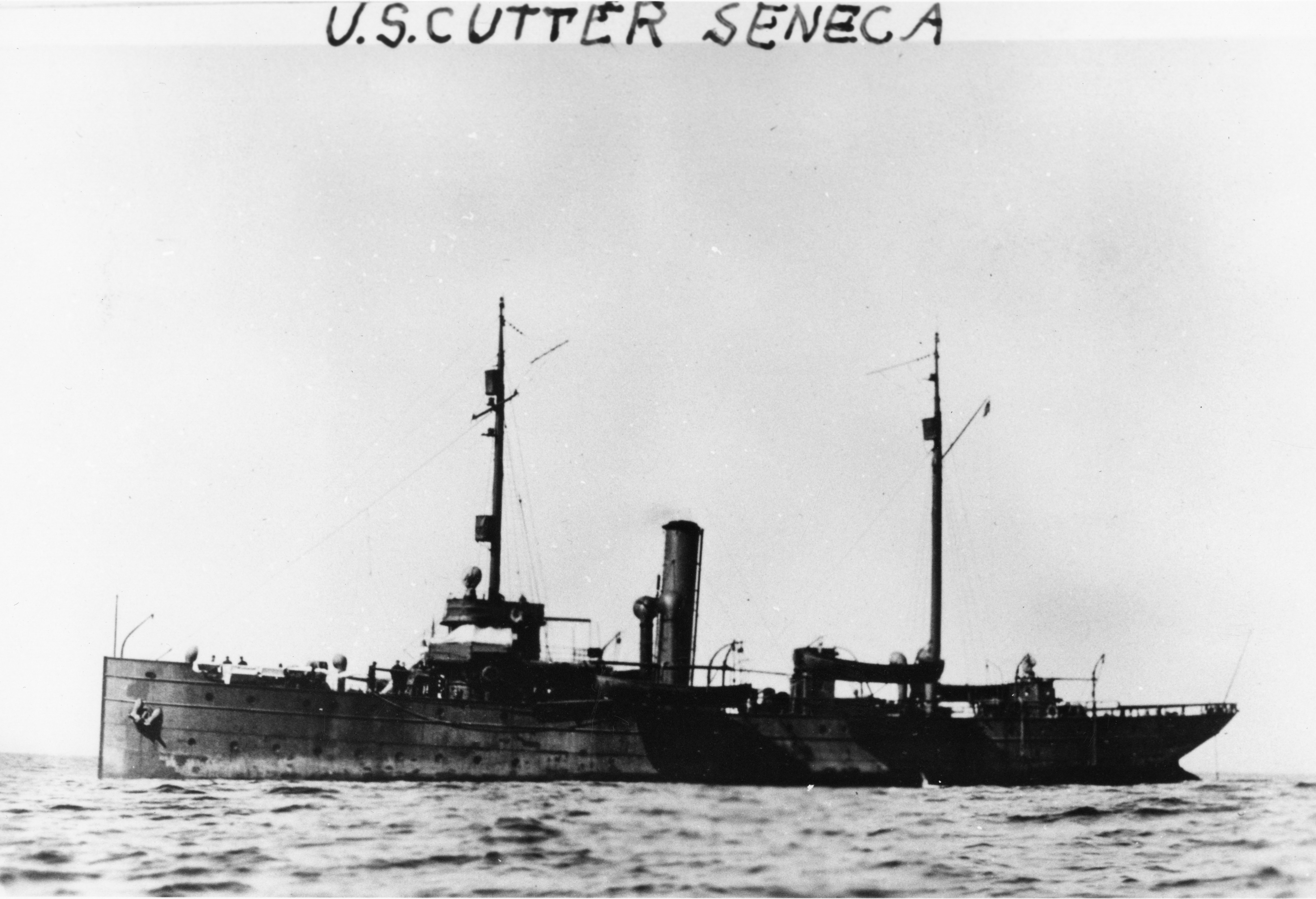

When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Coast Guard Cutter Seneca and its crew, along with the rest of the Coast Guard, were transferred to the Navy Department. Seneca was then selected for overseas duty and overhauled, refitted and re-armed before departing the U.S. in late August 1917. On Sept. 4th, Seneca arrived at Gibraltar, was assigned to Squadron 2, Division 6, of the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet Patrol Force, and began escorting convoys.

When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Coast Guard Cutter Seneca and its crew, along with the rest of the Coast Guard, were transferred to the Navy Department. Seneca was then selected for overseas duty and overhauled, refitted and re-armed before departing the U.S. in late August 1917. On Sept. 4th, Seneca arrived at Gibraltar, was assigned to Squadron 2, Division 6, of the Navy’s Atlantic Fleet Patrol Force, and began escorting convoys.

A year later, in September 1918, Seneca joined Convoy OM-99 consisting of 21 ships bound from England for Gibraltar. It was the 26th convoy for Seneca’s cuttermen. For 11 of them it would be the last. On Monday, Sept. 16th, at 11:30 a.m., a U-boat torpedoed the convoy ship S.S. Wellington. Seneca sped to the vessel’s assistance and, within minutes, the U-boat was sighted a few hundred yards away. Seneca’s crew fired three shots at the sub before it submerged then the cutter dropped depth charges to keep it down.

Wellington was in bad shape with torpedo damage in the forepeak. The ship’s master believed the ship would stay afloat, but only 11 of his 42 crewmen volunteered to stay on board. Seneca 1st Lt. Fletcher Brown volunteered at once to assist Wellington’s master and almost the entire crew of Seneca wanted to go with him. Nineteen of these volunteers were selected to join Brown. Meanwhile, the Navy destroyer USS Warrington had been notified and was on its way to assist Wellington.

Wellington was in bad shape with torpedo damage in the forepeak. The ship’s master believed the ship would stay afloat, but only 11 of his 42 crewmen volunteered to stay on board. Seneca 1st Lt. Fletcher Brown volunteered at once to assist Wellington’s master and almost the entire crew of Seneca wanted to go with him. Nineteen of these volunteers were selected to join Brown. Meanwhile, the Navy destroyer USS Warrington had been notified and was on its way to assist Wellington.

At 12:30 p.m., Seneca left the scene to rejoin the convoy. Boarding the Wellington, Brown posted lookouts and took charge of the ship with the master navigating to the nearest port at Brest, France. The stricken ship was still in sub-infested waters carrying valuable cargo to the Allies, so Brown broke out ammunition and started drilling a gun crew. Repairs were made below decks and, by 1:00 p.m., the ship began to move ahead. By 2:00 p.m., Wellington’s speed was increased until it made seven and a half knots. The ship was taking water in its Number 2 hold, but by driving the pumps the crew held the water level to only three and a half feet. However, by 7:00 p.m., that evening, the ship’s bow was down. Brown managed to bring the vessel’s bow back up long enough to regain its course, but Wellington’s bow finally submerged again elevating the propellers above the water’s surface.

That night, a storm came up and seas grew heavy with waves crashing over the bow. There was only one lifeboat on board Wellington and Brown mustered all the men beside it except the radio operator  and three men operating the pumps. He planned to remain aboard the ship with these four men while the others stood by to assist in the floating lifeboat. One Seneca man and seven Wellington men were lowered with the boat, requiring the others to slide down the falls into the boat after it reached the water. Fearful that the boat would be smashed against the ship by heavy seas, one of Wellington’s men cut the securing line and the lifeboat quickly drifted away. The eight men tried to row back to the Wellington, but the large lifeboat manned by a small crew of inexperienced oarsmen was no match for high winds and heavy seas.

and three men operating the pumps. He planned to remain aboard the ship with these four men while the others stood by to assist in the floating lifeboat. One Seneca man and seven Wellington men were lowered with the boat, requiring the others to slide down the falls into the boat after it reached the water. Fearful that the boat would be smashed against the ship by heavy seas, one of Wellington’s men cut the securing line and the lifeboat quickly drifted away. The eight men tried to row back to the Wellington, but the large lifeboat manned by a small crew of inexperienced oarsmen was no match for high winds and heavy seas.

Brown was left behind with 18 of his men and five Wellington men. He set them to building makeshift life rafts. Meanwhile, the ship continued sinking by the bow. The radio operator was in contact with USS Warrington and continued sending position reports. Wellington fired rockets, and at 2:30 a.m. on the 17th, Warrington responded with rockets, which were s een off the port bow. The Wellington listed rapidly and Brown gave the order to abandon ship. As the ship’s stern rose into the air, Brown continued using a flashlight to signal the USS Warrington in the distance. Meanwhile, Wellington’s boilers exploded and the vessel’s stern rose up for the final plunge.

een off the port bow. The Wellington listed rapidly and Brown gave the order to abandon ship. As the ship’s stern rose into the air, Brown continued using a flashlight to signal the USS Warrington in the distance. Meanwhile, Wellington’s boilers exploded and the vessel’s stern rose up for the final plunge.

Before the Wellington left the surface, Brown jumped into the roiling waters and swam clear into the darkness. Hearing cries for help, he swam out to his men clinging to flotsam, advised them not to ingest sea water and extinguished floating calcium lights s o they would not lure the men off their planks. After about three and a half hours in the water, Brown was rescued in a semi-conscious state and later developed pneumonia from exposure. Eight other Seneca crewmembers were rescued with one dying shortly after rescue. In all, 11 Seneca men and five Wellington men perished.

o they would not lure the men off their planks. After about three and a half hours in the water, Brown was rescued in a semi-conscious state and later developed pneumonia from exposure. Eight other Seneca crewmembers were rescued with one dying shortly after rescue. In all, 11 Seneca men and five Wellington men perished.

Among the eight other Seneca survivors rescued was coxswain James Osborn, who supported hypothermic shipmate coxswain Jorge Pedersen, swam to a small raft with the semi-conscious man, and held him securely between his legs. In the hours that followed, they were washed overboard several times, but each time Osborn recovered his shipmate and hoisted him back on the pitching raft. Finally, sighting USS Warrington, Osborn semaphored “I’m all right but he’s gone unless you come right away.” Warrington quickly recovered both men.

After the Wellington episode, Seneca escorted four other convoys, several times encountering submarines. The cutter was moored at Gibralta

The cutter was moored at Gibralta r on Nov. 11, 1918, when the armistice was signed ending World War I. During the war, the cutter escorted 30 convoys consisting of about 580 ships. Only four were lost and, from those four ships, 139 survivors were rescued. The cutter responded to 21 submarines had four close calls with torpedoes. During its convoy escort mission, Seneca is believed to have sunk one submarine.

r on Nov. 11, 1918, when the armistice was signed ending World War I. During the war, the cutter escorted 30 convoys consisting of about 580 ships. Only four were lost and, from those four ships, 139 survivors were rescued. The cutter responded to 21 submarines had four close calls with torpedoes. During its convoy escort mission, Seneca is believed to have sunk one submarine.

After the war, Seneca remained at Gibraltar for several months and then returned to the U.S. by way of Algeria, France, and England. On Aug. 28, 1919, Seneca was transferred back to the Treasury Department and the cutter returned to its base at Tompkinsville, New York.

Seneca’s cuttermen were awarded 19 Navy Cross Medals total; 10 survivors and nine posthumously. In addition, one received a posthumous Distinguished Service Medal and one of the survivors received the Gold Lifesaving Medal. All of the men received a commendation from the senior Royal Navy officer at Gibraltar for their bravery and heroic efforts. All told, this rescue attempt proved the most honored event in Coast Guard history.