Pacific Island men and women have participated in the United States Coast Guard for over 170 years, playing a vital role in the history of the service and its predecessor agencies of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service and the U.S. Lighthouse Service.

Pacific Island men and women have participated in the United States Coast Guard for over 170 years, playing a vital role in the history of the service and its predecessor agencies of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service and the U.S. Lighthouse Service.

Cultural contact with Pacific Island peoples came with expansion of the nation’s boundaries to the Pacific Ocean. Seventeen seaman from Hawaii signed-on to serve aboard Revenue Cutter C.W. Lawrence, first cutter in the Pacific, for the final leg of a voyage from the East Coast to its new homeport of San Francisco. Many, and perhaps all, of these men were native Hawaiian. This event marks the beginning of Pacific Islander participation in the Coast Guard, making Pacific Island-Americans the third longest-serving minority group in the Coast Guard.

Cultural contact with Pacific Island peoples came with expansion of the nation’s boundaries to the Pacific Ocean. Seventeen seaman from Hawaii signed-on to serve aboard Revenue Cutter C.W. Lawrence, first cutter in the Pacific, for the final leg of a voyage from the East Coast to its new homeport of San Francisco. Many, and perhaps all, of these men were native Hawaiian. This event marks the beginning of Pacific Islander participation in the Coast Guard, making Pacific Island-Americans the third longest-serving minority group in the Coast Guard.

Expanded revenue cutter operations in the Pacific and the purchase of Alaska in 1867 presented an opportunity for more Pacific Island natives to enlist on West Coast cutters. During the late 1800s, Pacific Islanders frequently signed-on to serve aboard those revenue cutters. As foreign nationals, these men filled non-rate food service and domestic positions in ratings such as steward and “boy.” By the end of the century, many Pacific-based cutters employed Pacific Island non-rates of this kind.

In 1898, Congress passed legislation annexing the Hawaiian Islands as a U.S. territory. That same year, the U.S. annexed the former Spanish territory of Guam after the Spanish were defeated in the Spanish-American War. These measures allowed greater numbers of native Pacific Islanders to enlist. In 1904, Revenue Cutter Thetis became the first cutter stationed in Honolulu. For over 10 years, Thetis served the Hawaiian Islands and Midway Island, and signed-on Hawaiian crew members to serve in non-ranking enlisted jobs. By that time, the eastern islands of Samoa had become the U.S. territory of American Samoa. As more Pacific islands became territories or protectorates of the U.S., their inhabitants became eligible to enlist in the service.

In 1898, Congress passed legislation annexing the Hawaiian Islands as a U.S. territory. That same year, the U.S. annexed the former Spanish territory of Guam after the Spanish were defeated in the Spanish-American War. These measures allowed greater numbers of native Pacific Islanders to enlist. In 1904, Revenue Cutter Thetis became the first cutter stationed in Honolulu. For over 10 years, Thetis served the Hawaiian Islands and Midway Island, and signed-on Hawaiian crew members to serve in non-ranking enlisted jobs. By that time, the eastern islands of Samoa had become the U.S. territory of American Samoa. As more Pacific islands became territories or protectorates of the U.S., their inhabitants became eligible to enlist in the service.

In 1906, Samuel Amalu joined the U.S. Lighthouse Service and became Hawaii’s renowned dean of lighthouse keepers. Amalu took charge of the Kilauea Lighthouse on April 9, 1915, and had the longest tenure of any lightkeeper at Kilauea serving there for 10 years. By the time he started at Kilauea, he had already served as keeper at Kawaihae Light on the island of Hawaii and at Barber’s Point Light on Oahu. A trailblazer among Hawaii’s lightkeepers, Amalu laid a path of discipline and devotion to duty for subsequent lighthouse keepers in Hawaii.

In 1908, Manuel Ferreira joined the Lighthouse Service and served as the keeper of seven Hawaiian lighthouses during his career. He was born in 1885 and became known as “one of the grand old men of Hawaiian lighthouse lore.” He ultimately became the keeper of the Kauiki Head Light Station on Maui. In 1919, Ferreira rescued the crew of a Japanese fishing trawler that ran aground off Barber’s Point, Hawaii, where he served as the lightkeeper. He was also instrumental in saving the schooner Bianca and its crew in 1923. From  1927 through 1929, he served as keeper of the Molokai Light Station, located only two miles from the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement on the island of Molokai. He retired in 1946 after 38 years of dedicated service.

1927 through 1929, he served as keeper of the Molokai Light Station, located only two miles from the Kalaupapa Leper Settlement on the island of Molokai. He retired in 1946 after 38 years of dedicated service.

Numerous Pacific Islanders served during the World Wars. For example, Hawaiian James Kimokeo served during World War I. He was a water tender aboard the Cutter McCulloch in 1917, during a collision that sank the cutter off the coast of California. Later, he served as a surfman at Alaska’s only boat station located in Nome, Alaska, when the Spanish Flu Pandemic decimated the Native Alaskan population in that area. During World War II, Pacific Island men also joined the Coast Guard as wartime “temporary reservists.” Coast Guard Temporary Reservist Duke Paoa Kahinu Mokoe Hulikohola Kahanamoku, also known as “The Big Kahuna,” later became Hawaii’s greatest athlete, film star, Olympian and founder of international surfing.

At the start of U.S. involvement in World War II, on Dec. 7, 1941, native Hawaiian Coast Guardsman Melvin Kealoha Bell manned the Diamond Head radio station during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, warning commercial vessels that a surprise attack was underway. In 1944, Radioman 1st Class Bell advanced to a wartime rate of Chief Radioman, becoming the first Pacific Islander to make chief petty officer. During this time, he served within the U.S. Navy’s intelligence office helping crack the Imperial Japanese Navy’s secret codes. After World War II, Bell’s wartime rank was reduced to radioman first class. However, in 1949, he was advanced to the permanent rate of chief electronics technician, becoming first Pacific Islander advanced to the permanent rate of chief petty officer. In 1958, Bell advanced to master chief petty officer, , becoming the first minority master chief petty officer in the Coast Guard. He will soon be the first Pacific Island-American namesake of a Coast Guard cutter.

In 1947, Palau, the Marshall Islands, Northern Mariana Islands and the islands of Micronesia, became part of the U.S. administered Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. In the post-war years, these territories became part of the Coast Guard’s area of responsibility administered from bases in Hawaii, Guam, Saipan, and American Samoa. In the late 20th century, men and women from these trust territories began to join the ranks of the Coast Guard.

On July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman ordered the integration of the U.S. armed forces with Executive Order #9981, which opened all enlisted ratings to U.S. citizens no matter their race or ethnicity. Since the adoption of the Pacific Trust Territory and Truman’s executive order, men and women have enlisted from numerous island territories, such as Palau, Marshall Islands, Northern Marianas and Micronesia.

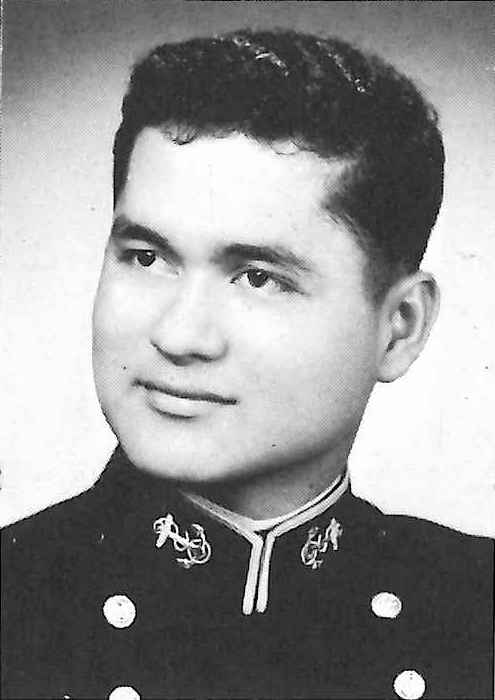

Ethnically Pacific Island men and women began to matriculate from the Coast Guard Academy in the 1960s. In 1968, Juan T. Salas became first Pacific Islander to graduate from the Coast Guard Academy and first Chamorro individual to graduate from any U.S. military academy. In addition to becoming the first Pacific-Island American to graduate the Academy, he was also the first one to receive a Coast Guard officer’s commission. In 1987, Laura H. O’Hare became first Hawaiian native and female Pacific Islander to graduate from the Coast Guard Academy and the first to receive a Coast Guard officer’s commission.

In 1986, Juan Salas became the first Pacific Islander to command a cutter, the Coast Guard Cutter Lipan and, in 1990, he was promoted to the rank of captain becoming the first Pacific Islander to reach that rank. In 1992, Salas become and first Pacific Island commander of the Coast Guard base at Guam and his son Matthew J. Salas became a cadet at the Coast Guard Academy making him and his father the first father-son Pacific Islander attendees of the Academy.

Pacific Island men and women have also joined the officer ranks through Officer Candidate School and chief warrant officer ranks. In 1976, Chamorro Ken J. Balajadia graduated from Officer Candidate School, becoming the first known Pacific Islander to graduate from OCS. In 1977, Ensign Balajadia received his Coast Guard wings becoming the first Pacific Islander Coast Guard pilot. He flew Coast Guard C-130s for a few years before leaving the service to accept a position as a civilian airline pilot. In 1991, Samoan native Michael Sakaio graduated from Officer Candidate School and received his commission as an ensign to become the first Samoan-American to graduate from OCS and receive an officer’s commission. A year later, Hawaiian native Wayne Stachel promoted to chief warrant officer followed in 1997 by Chamorro Frank Palacios. Since 2000, other service members from Samoa, Guam, Palau, Marshall Islands and Saipan have joined the chief warrant officer ranks.

For over 170 years, thousands Pacific-Island men and women have served with distinction in the United States Coast Guard. They have been diligent members of the long blue line and they will play an important role in the service in the 21st century.